The Discovery Channel's Princess Problem: Website Recommends Mani-Pedi Kits To Girls (And Ant Farms To Boys)

For parents looking for science education toys for their kids, the Discovery Channel’s website neatly divides up the section: one for boys, and one for girls. But where boys get items such as ant farms and simulated frog dissection kits, girls are offered a "mani pedi party" kit and a “duct tape party” kit that teaches them how to make headbands and jewelry.

This raises the question: Does it make sense to gender science education toys? Statistics show that an alarming number of girls stop being interested in math and science at an early age, which can result in a disparity between women and men in the sciences later on. Are these gendered science toys -- some of which seem more like crafting toys -- alienating girls from science, subtly telling them it's not for them?

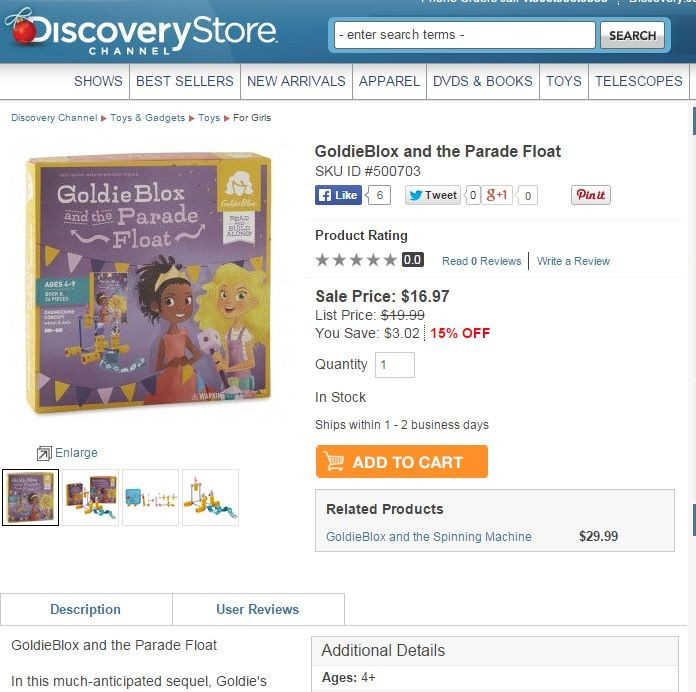

A closer look at how the gender differentiation is expressed in the toys is telling. Not only do boys get more science-oriented toys that don't refer to their gender, none of their kits on the Discovery site present limiting visual representations of what a budding male scientist would look like, whereas the female images on the kits for girls are conventionally feminine and decked out in jewelry and other such feminine markers. Discovery Channel did not respond to a request for comment.

International Business Times asked Rebecca Hains, author of “The Princess Problem: Guiding Our Girls Through the Princess-Obsessed Years,” what she thought about the strategy of using "princesses" and, for the GoldieBlox educational toys, a character with cascading curls named “Goldie” to get girls into engineering. Are these toys even teaching them anything about constructing things – or more about the construction of gender in a culture where girls and women are taught to see their looks as their most valuable asset?

“Many young girls go through a phase in which they adhere very strictly to associating only with princess-related toys and clothing,” said Hains. “In this regard, it can be helpful to have princess-type characters that break stereotypes and actually engage in activities such as, say, engineering. So, for girls ages 4 to 5 who are going through this phase, princesses and ‘Goldie’ might be a decent way to broaden their horizons.”

But Hains believes that marketers and stores need to stop categorizing these toys for boys or girls; she thinks it would be better to group them according to the child’s interest.

“On the whole,” Hains said, “there are far more similarities between boys and girls than there are differences, and our society's constructions of gender in the toy aisles erases those similarities in a way that limits children's imaginations, aspirations and identities.”

In an analysis of science kits marketed to girls in 2011, Janet Stemwedel from Scientific American noted that there were several problems with "science" kits like "Spa Science." This kit features a Barbie lookalike soaking in a bubble bath and teaches girls how to make oatmeal masks and about aromatherapy -- about which she notes "there is science worth discussing in this neighborhood," wrote Stemwedel.

"The packaging here strikes me as selling the need for beauty product more emphatically than any underlying scientific explanations of how they work," she wrote. And although she thought it was a good message that "'girly' girls can find some element of science that is important to their concerns," she worried that the kits also seemed to convey that "being overtly feminine is a concern that all girls have (or ought to have)— and, that such 'girly' girls couldn’t possibly take an interest in science except as a way to cultivate their femininity."

There is a way of getting girls interested in science that doesn't put any gender constrictions on them. Peggy Orenstein, author of "Cinderella Ate My Daughter: Dispatches from the Front Lines of the New Girlie-Girl Culture," which looks at the dark side of "pink culture" -- told International Business Times that her daughter, who is not inherently a science-lover, attended a day-long UC Berkeley program for girls promoting science. The program had a number of gender-neutral workshops in which girls were invited to build lego robots and participate in a robot demolition derby, build a bridge and learn about engineering principles, learn to extract their own DNA and to examine live animals and learn about veterinary medicine.

"There wasn’t a sparkle in sight," said Orenstein, "and it was GREAT."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.