The Long Road To Austerity: A Bailout For Greece And An Angry Population Reject The Eurozone Deal

ATHENS -- The mood in Athens is heavy today. After six months of tough negotiations Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras has finally struck a deal with Greece's creditors, but it comes at a high cost.

“He should have taken us out of the euro. We would suffer, but we would have our pride and dignity.” Dimitris Kokkorakis, a 70-year-old pensioner and long-time supporter of Syriza, Tsipras' governing left-wing party, is not happy with the outcome of Monday’s talks. While some Greeks, in the long line for their pensions, are breathing a sigh of relief that the euro's set to stay, Kokkorakis, a former private sector employee, is unconvinced that life will improve. “This is permanent austerity and permanent poverty. If we had exited [the eurozone], we may have had a chance to grow again with social cohesion.”

Many of Syriza’s MPs agree with him -- 30 openly oppose the deal -- and Syriza’s partner in the coalition government, the Independent Greeks (ANEL), has not yet decided whether to back the agreement. Panayiotis Lafazanis, the leader of the Left minority platform and a minister in Tsipras' government, stated that he won’t vote for the agreement or resign from parliament. He’s supported by another minister, Dimitris Stratoulis, and the president of the Greek parliament, Zoe Konstantopoulou.

Despite the internal conflict, the program of austerity measures looks as though it will pass through Greek parliament. All opposition parties are supporting the deal and Tsipras will have a comfortable majority to move forward. But it's painful for Syriza, the party elected on an anti-austerity platform, to watch another rally outside parliament’s walls, as its former aspirations are replaced with the economic orthodoxy of the eurozone.

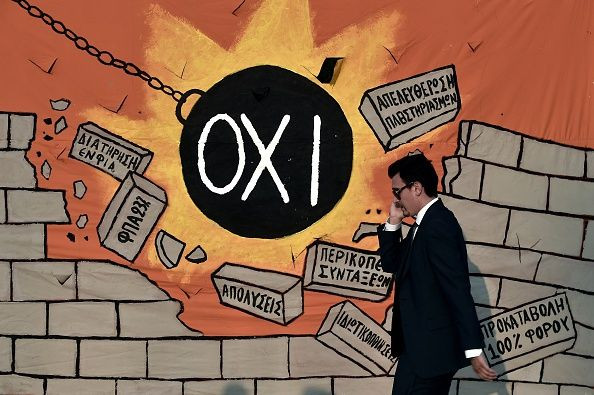

This paradoxical situation on the political field is reflected in Greek society. Many “no” voters in the April 5 referendum are disheartened by Monday’s turn of events. “I feel frustrated, disappointed and scared,” Penny Kalogeropoulou, a 40-year-old high-school teacher told the International Business Times. “I thought a change had happened in regards to the way society deals with its problems. This humiliation is only going to turn society to more conservative values.”

On Twitter, anti-austerity supporters ran a campaign under the hashtags #thisisacoup #TsiprasleaveEUsummit and #ΛέμεΟΧΙ (We say NO).

“People from all over the world stay by our side if you don't wish to be next in #Thisisacoup," wrote one user, and another added: “The principle of European solidarity should renounce revenge and humiliation."

Do not awake Italians & Spaniards!They should not be aware that they are next to come #ThisIsACoup https://t.co/j0kF8yhj6A

— Christodoulou Thanos (@ThanosChristo) July 13, 2015Not everybody is ruing Monday’s deal. Dimitris Stratouris, president of the trading association on the Greek island of Naxos, believes the harsh terms of the bailout are a necessary evil. “We desperately need a deal because the market is frozen,” he argues. Stratouris previously opposed raising value-added tax on the islands to 23 percent, fearing it would kill economic activity. But when he saw tourist operators canceling their bookings and the market drying up, he realized that an emergency settlement was needed. “We'll figure the rest after the agreement,” he says.

#GreekCrisis NO to #grexit Yes to #grentry or #grereturn

— Sergio Ferraiolo (@sirjoe7007) July 8, 2015The National Confederation of Commerce and Entrepreneurship has urged a fast “Grentry” suggesting that small- and medium-size businesses need financial support to cope with the crisis. During the past week, the Greek economy fell to its knees when transactions between companies collapsed. Monday’s agreement, along with the announcement that banks may open as soon as Thursday, was accepted with relief.

But the feeling of humiliation among the 61 percent of Greeks who won the vote against austerity, only to find themselves the losers one week later, is driving the political situation to a dead end. People are questioning the point of the European Union, if democratic votes are overturned in the name of economic stability. Kalogeropoulou is afraid that a new round of layoffs will start in the public sector, but that's not the most disturbing thing. “I'm annoyed that the idea that there's no point in fighting for your rights is now confirmed.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.