New Device Cleans Air, Produces Energy, Runs On Light

Turns out, air pollution is good for something — making energy.

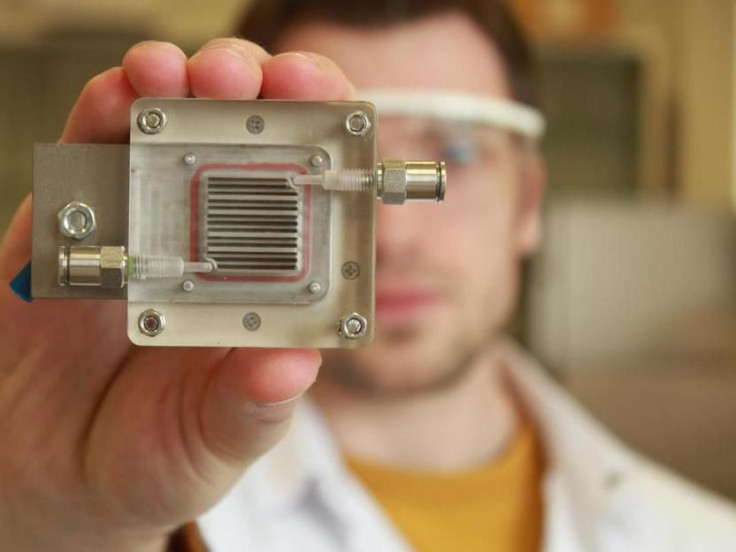

Belgian researchers have developed a device that runs on light, cleans the air and stores hydrogen extracted from the pollutants that can later be used in fuel cells. The key is a membrane made of nanomaterials that act as catalysts, producing hydrogen and breaking down pollutants.

"We use a small device with two rooms separated by a membrane," Professor Sammy Verbruggen of the University of Antwerp and KU Leuven said Tuesday in a press release. "Air is purified on one side, while on the other side hydrogen gas is produced from a part of the degradation products. This hydrogen gas can be stored and used later as fuel as is already being done in some hydrogen buses, for example."

Read: EPA Administrator Pruitt Admits Humans Contribute To Global Warming

Verbruggen said the membranes in the past have been used to extract hydrogen from water.

“We have now discovered that this is also possible, and even more efficient, with polluted air,” he said.

Though the device works in a similar way as solar panels, it does not generate energy directly.

“We are currently working on a scale of only a few square centimetres. At a later stage, we would like to scale up our technology to make the process industrially applicable. We are also working on improving our materials so we can use sunlight more efficiently to trigger the reactions,” Verbruggen said.

"The idea is that we're trying to develop technology that copes with polluted air — so you can clean your air and provide a clean living environment — while at the same time producing an alternative source of energy," he told Mic. "But this is just the first proof of concept."

Read: Immune System Can Be Reprogrammed With Them, Researchers Say

The development could have a major impact on developing economies like those in China and India, which are both on the edge of an energy crisis and battling serious air pollution problems although Verbruggen cautions the device is not “the holy grail.”

Research presented in February at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington estimated more than 5.5 million people die prematurely each year due to air pollution, more than half of them in China and India while the International Energy Agency said an estimated 240 million people in India lack access to electricity and China is on the cusp of mandatory power rationing for industry.

The devices also could be used to target specific industries.

"For instance, if you go to the textile industry, I can imagine they have to deal with some very big waste streams," Verbruggen said. "If you can use [this] to purify waste gases, then the industry can always meet environmental regulations."

A report published in the journal Cancer Monday found poor air quality was strongly associated with increased cancer rates. The research indicated areas with poor environmental quality saw cancer rates of 490 per 100,000 people compared to 451 per 100,000 in less polluted areas. Polluted water and land had no measurable effect, the research by the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health indicated.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.