The World Upside Down: Why Emerging Economies Are Helping To Save Europe

A new world order still seemed a long way off at the turn of the century. The Asian economies had just experienced the major financial crisis of 1997, and the International Monetary Fund stepped in afterward with a widely criticized program to stabilize regional currencies.

More than a decade later, Asian economies are making major contributions to the IMF's initiative to prop up financial systems in debt-ridden Europe. In other words, it's the world turned upside down, and in the space of twelve short years.

Asian and emerging economies account for more than 40 percent of the new IMF firewall bailout fund to the European Union. $189 billion of the promised $456 billion is coming from countries outside Europe. No money has yet been offered by the U.S. or Canada, who say the amount is too little to save Europe and that the Europeans should foot the bill independently.

So even as the West itself is divided on saving the European financial system, why is the rest of the world, including many countries still largely impoverished in per capita terms, coming to the rescue?

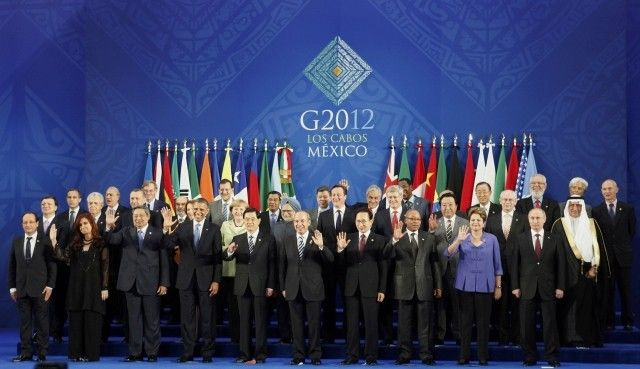

Asian countries are dominating non-European sources: Japan is giving $60 billion, China is offering $43 billion, South Korea is giving $15 billion, $10 billion is coming from India. Singapore, a tiny city-state with an economy bigger than 17 of the EU's 27 countries, will provide $4 billion and Thailand, the Philippines, and Malaysia offered $1 billion each. Outside Asia, $15 billion is coming from Saudi Arabia, $10 from Russia, Brazil, and Mexico each, and $2 billion from South Africa. In this new financial world order, former colonies are now paying to save their former rulers from disaster.

Many of the above governments, including some of the more well-to-do ones, will be getting plenty of flak at home as citizens complain that the money should go to much-needed domestic spending. But the funds aren't pouring from the goodness of the emerging countries' hearts. They are coming with strings attached.

The bailout fund's payers, especially the BRICS -- Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa-- are giving large amounts because they want something in return, and in fact they have already asked for it.

The BRICS released a joint statement on Tuesday saying that these new contributions are being made in anticipation that all the reforms agreed upon in 2010 will be fully implemented in a timely manner, including a comprehensive reform of voting power and reform of quota shares.

That refers to requests to redistribute voting power within the IMF to grant a larger voting bloc to emerging economies. Domestic legislatures in other IMF member countries have not yet ratified the new changes, increasing frustration within emerging economies that they are being locked out of a major international economic institution even as they contribute increasing amounts to international economic growth.

When eventually in place, the new voting ratios would push China to third place in terms of votes in the IMF (behind the U.S. and Japan). Currently China has fewer voting shares than France or the United Kingdom despite having an economy almost five times bigger. Last year, before an adjustment, India still had voting percentages lower than the Netherlands, a country with a population more than 70 times smaller and an economy one-sixth the size.

Under new voting adjustments, emerging market and developing countries would have 44.7 percent of the votes in the IMF, more than the 41.2 percent allotted to the G7, the seven powers that until now have ruled the roost.

The U.S. would still hold the largest number of votes at 16.5 percent. After all, there's a reason why the IMF is headquarters in Washington, D.C. -- it was meant to be a major mechanism of international financial stability in the aftermath of World War II, within an economic framework largely ensured by the U.S.

Last June, the BRICS called the tradition of appointing a European, usually a French national, to head the IMF an obsolete practice. With the money and the influence they are now wielding, they may soon get a chance to upend that 67-year tradition.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.