'Game of Thrones,' Shondaland: Why Are So Many Main Characters Dying On TV?

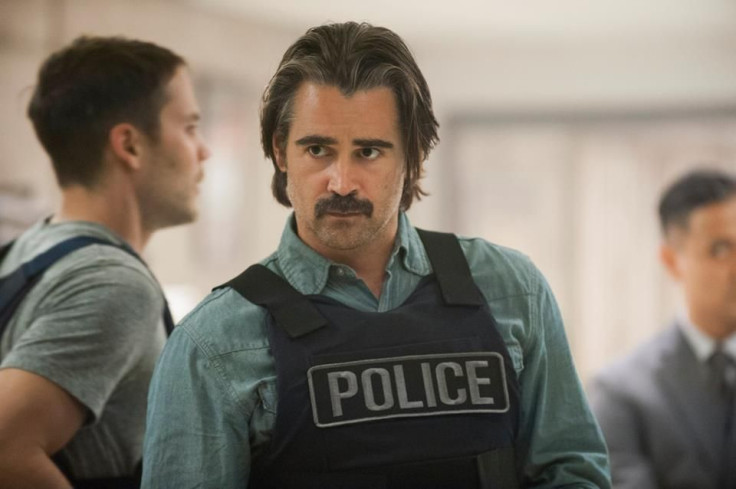

A week ago, the second episode of “True Detective” Season 2 ended with a cliffhanger: Detective Ray Velcoro (Colin Farrell) was shot multiple times in the chest with a shotgun. That the central character could be killed off in the second episode of the series wasn't as shocking as what happened next: In episode three we learned Velcoro actually survived due to a silly plot contrivance.

Killing off a main character -- and a mega-star -- almost seemed less weird than bringing him back the next week. That's because we've been conditioned by the major purveyors of high-end TV to expect main characters will die, pretty much any time.

Consider the ever-growing list of leads who have died in the past year or so: Dr. Derek "McDreamy" Shepherd ("Grey's Anatomy"). Will Gardner ("The Good Wife"). Zoe Barnes ("House of Cards"). Ned Stark, Jon Snow and almost every character on “Game of Thrones.” "American Horror Story" and "The Walking Dead" are known for their willingness to kill their leads. It’s a dangerous time to be a major character on a television show.

Over the past few years, we’ve seen major changes in the television landscape. With shows like “Game of Thrones” and ABC’s "Shondaland" dominating the zeitgeist, it’s become apparent that one of the trends in this golden age of television is the willingness to kill major characters. As a narrative device, killing off a major character is a show's way of making a statement.

"It's setting the show apart in terms of, 'This is not going to be the show you thought it was.' The stakes are very high," Dr. Amanda Lotz, a University of Michigan professor who specializes in television and media studies, told International Business Times.

ABC’s cult hit “Lost” used death as a destabilizing force to challenge audience’s expectations, a factor in its six-year run on network TV. “But if you kill a significant main character, well, then, suddenly the jeopardy for all your main characters seems a lot more real,” Carlton Cruise, showrunner of “Lost,” told Variety.

In the spirit of “Lost,” let’s flash back to the first-season finale of "24" in 2002. After foiling a terrorist plot, Jack Bauer (Kiefer Sutherland) returns to the Counter Terrorism Unit to find his wife, Teri (Leslie Hope), murdered by a mole in the agency. It was a shocking, gut-wrenching and powerful moment of television, and one of the show’s best, reminding the audience that the stakes were indeed quite high. But, this narrative decision was also rather rare for a show on a broadcast network, where stability, consistency and longevity were priorities and killing a main character was virtually taboo.

Fast-forward to today, and there are Teri Bauers everywhere. Moreover, killing a main character, even on broadcast, has become expected. At last summer’s Television Critics Association press tour, Bruno Heller, the showrunner of Fox’s “Gotham,” was asked if he worried that he won’t be able to kill off any important characters in the prequel series because of their importantance to the future of the Batman mythology.

"It's a sad thing if you can only build tension by killing people," Heller answered, as reported by HitFix.

Killing To Stay Alive

What accounts for TV's rising kill rate? Lotz believes it has to do with two factors: increased competition and the opening storytelling possibilities. And she traces both of these to the emergence of the cable drama.

When cable dramas entered the scene, they needed to carve out their place in the television landscape. To do so, they focused on giving audiences things they couldn’t get on broadcast. Lotz notes that with changing business models, including shorter seasons, less emphasis was placed on character longevity. Thus, if the story demanded it, like in “The Shield” or “Deadwood,” these cable dramas could kill main characters. We've seen this continue on shows like "Game of Thrones," but also on "American Horror Story," "Fargo" and other anthology series that place an even higher premium on reinvention than on consistency.

The cast of HBO's "The Sopranos," the show many credit with jumpstarting this golden age, was paranoid about getting killed off because of the show's tendency to send major character swimming with the fishes. "There was a lot of fear," Michael Imperioli, who played Tony Soprano's nephew Christopher Moltisanti and also wrote several episodes, told the New York Times in 2007. "People wanted to know about being killed. I kept pretending I didn’t know.”

Shock Value

Now there are more scripted shows on the air than ever before, so it's even harder to find ways to cut through the clutter, especially for broadcast network shows. The death of a major character, then, becomes a can’t-miss event that’s meant to shock the audience and re-energize them. It goes from a creative decision to a personal tool, as in the case of shows like Shonda Rhimes' "Grey's Anatomy" and "Scandal," where major character deaths feel more like the norm than the exception. Moreover, these events are highly promoted, which is something you don’t see much on cable.

“There are just so many shows on the air right now, and it’s so difficult to get publicity or attention that if you have something newsworthy happen on your show—like the death of a major character—that’s going to drive social media and attention,” Lotz said.

Promos for the “Grey’s Anatomy” episode where McDreamy died touted it as the episode “America can’t forget.” Actually, the death of main characters has become an oft-used tool in Shonda Rhimes’ work, which has drawn criticism.

“She loves to use death as a hand grenade, blowing up plotlines for the sake of a stunt,” the AV Club’s Gwen Ihnat wrote in a piece about the main character's death.

In this “anything can happen” environment, however, an audience’s viewing experience is changed, Lotz says.

“What happens when anything can happen? You have to watch more closely,” Lotz said, noting how this is beneficial for broadcast channels, which are advertiser-driven. “If you’ve got an audience pulled in that closely— that anything can happen and they have to watch—that audience is sitting there for the commercials as well.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.