Icy Planets Could Have Subsurface Oceans Due To Gravitational Interaction With Moons

Thanks to Saturn’s moon Enceladus, we already know that a body with an icy crust can still have a subsurface ocean of liquid water. A new NASA study proposes that the number of other icy bodies that also have liquid water below the surface is possibly quite high in the solar system.

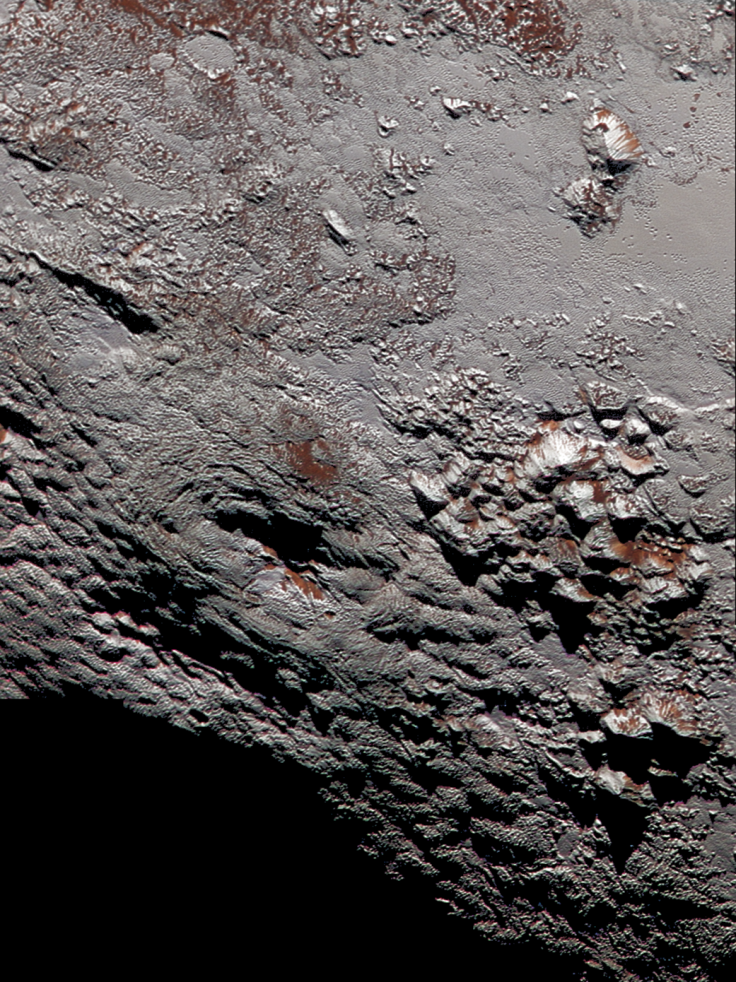

The study considers bodies in the outer solar system, beyond the orbit of Neptune, aptly named Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs). These bodies, that include the erstwhile planet Pluto, are relatively far from the sun and have surface temperatures of close to 350 degrees Fahrenheit below zero (about 200 degrees Celsius below zero), temperatures at which liquid water cannot exist.

But the study suggests that gravitational interaction with their moons could cause enough heat in the interior of these large bodies to sustain liquid oceans beneath the frigid surfaces. And if its findings are right, it could have implications on our search for potentially habitable places beyond Earth, or even other forms of life.

“These objects need to be considered as potential reservoirs of water and life. If our study is correct, we now may have more places in our solar system that possess some of the critical elements for extraterrestrial life,” Prabal Saxena of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, who was lead author of the research, said in a statement Thursday.

The researchers think liquid water could exist on Pluto and outer solar system bodies because when they analyzed light reflected from some TNOs, they found signatures of crystalline water ice and ammonia hydrates. However, due to the extreme cold on TNOs, water ice crystals are not orderly in the way we see them on Earth, and space radiation breaks down the ammonia hydrates. To explain their presence despite conditions that would prevent them from existing, the researchers suggest they came to the surface from an interior liquid water source, erupting through a process called cryovolcanism.

Radioactivity in the cores of planetary bodies, including TNOs, is responsible for most of the long-lived heat inside them. But that heat dissipated over time, as radioactive elements decay into stable ones, and it was not enough to explain the hydrothermal activity seen on Enceladus. It is also not enough to explain the liquid subsurface oceans thought to exist on TNOs. Enter the concept of tidal heating.

“Large collisions between celestial objects can generate moons when material is splashed into orbit around the larger object and coalesces into one or more moons under its own gravity. Since collisions occur in a huge variety of directions and speeds, they are unlikely to produce moons with perfectly stable orbits initially. As a collision-generated moon adjusts to a more stable orbit, mutual gravitational attraction causes the interiors of the parent world and its new moon to repeatedly stretch and relax, generating friction that releases heat in a process known as tidal heating,” NASA explained in the statement.

The research team used tidal heating equations to estimate how much heat it could be contributing to a number of TNOs, including Pluto and the net-biggest known TNO, Eris.

“We found that tidal heating can be a tipping point that may have preserved oceans of liquid water beneath the surface of large TNOs like Pluto and Eris to the present day,” Wade Henning of NASA Goddard and the University of Maryland, College Park, a coauthor of the study, said.

Titled “Relevance of tidal heating on large TNOs,” the paper was published Nov. 24 in the journal Icarus.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.