New Coronavirus Mutation Spreading In Houston Is More Infectious, Study Reveals

KEY POINTS

- A mutation to the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 has been identified as causing the spike in confirmed cases in Houston

- It made the coronavirus more infectious, especially among low-income communities

- The mutation, however, didn't increase the virus' virulence

The peak in COVID-19 cases in Houston and Harris County in June and July was apparently driven by a new and more infectious mutation of the coronavirus, said a published study from the Houston Methodist Hospital. This strain is still around.

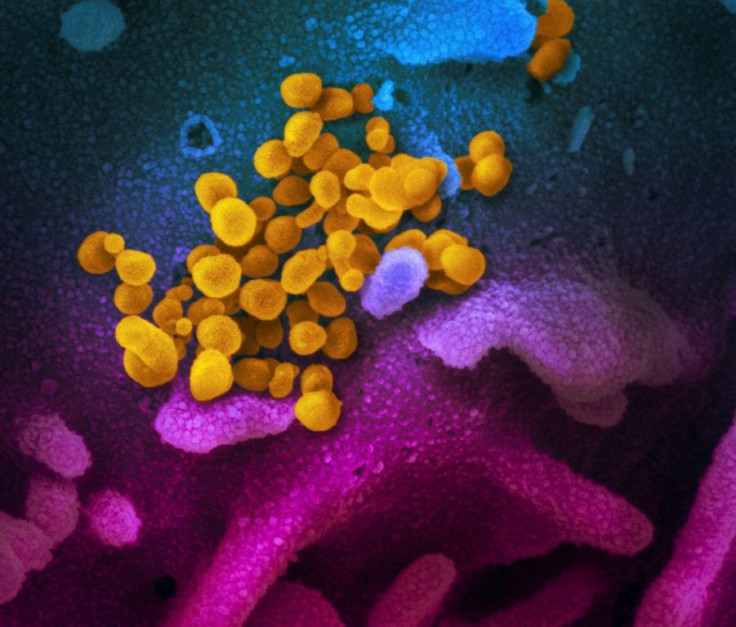

SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), the virus that causes COVID-19, is mutating as it adapts to defend itself to the human body's immune system. The Houston Methodist study examined 5,085 genomes from viruses recovered during the infection waves in Houston, including the massive second wave that started in late May.

A preprint of the study, which was published Wednesday on the MedRxiv website, found 99% of the samples in the second wave carried a mutation identified as "D614G." The more “spikes” on the crown of this mutation allowed it to better adhere to and infect human cells. D614G is a variant of the Gly614 amino acid replacement in the spike protein. Previous studies had indicated that the the strain carrying the D614G mutation had replaced those with D614 as the dominant strain.

"Virtually all strains in the second wave have a Gly614 amino acid replacement in the spike protein, a polymorphism that has been linked to increased transmission and infectivity," said the study. "Patients infected with the Gly614 variant strains had significantly higher virus loads in the nasopharynx on initial diagnosis."

Fortunately, researchers found little evidence that the new mutation has made SARS-CoV-2 deadlier. The study also affirmed previous findings showing the severity of COVID-19 is more strongly linked to patients’ underlying medical conditions and genetics rather than to increased viral load.

"We found little evidence of a significant relationship between virus genotypes and altered virulence, stressing the linkage between disease severity, underlying medical conditions, and host genetics," according to the study.

People taken sick during the second wave of infections were younger and had fewer co-morbidities. They were also from low-income communities.

"Although the full array of factors contributing to the massive second wave in Houston is not known, it is possible that the potential for increased transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 with the Gly614 may have played a role, as well as changes in behavior associated with the Memorial Day and July 4th holidays, and relaxation of some of the social constraints imposed during the first wave," said the study.

The study is the first analysis of the molecular architecture of SARS-CoV-2 in two infection waves in a major metropolitan region, in this case Houston. Researchers said their findings will help others understand the origin, composition and trajectory of future infection waves.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.