Obama And Canada’s Justin Trudeau Vow To Tackle Methane Emissions From Oil And Gas Sector

U.S. President Barack Obama and Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau have forged a pact to fight climate change.

Outlined Thursday morning, the joint agreement largely focused on methane, a potent greenhouse gas that can leak from crude oil and natural gas wells. Obama and Trudeau committed to slashing oil-and-gas methane emissions by between 40 percent and 45 percent from 2012 levels by 2025, a target the Obama administration set last year.

The leaders also pledged new cooperation in preserving the Arctic environment, accelerating clean-energy development and upholding the agreements made at the United Nations climate change talks in Paris last year. Trudeau’s trip to Washington was the first state visit by a Canadian leader in 19 years and signaled an end to the frosty U.S.-Canadian relations that had existed under previous Prime Minister Stephen Harper.

In conjunction with the pact presented Thursday, U.S. officials said they would immediately push to regulate emissions from the hundreds of thousands of oil-and-gas facilities sprawled across the country.

The measures are part of Obama’s broader strategy to tackle methane. Until recently, most American efforts to address climate change have focused on carbon dioxide emissions, which account for more than two-thirds of total U.S. greenhouse gas pollution. Methane constitutes about 10 percent of overall emissions.

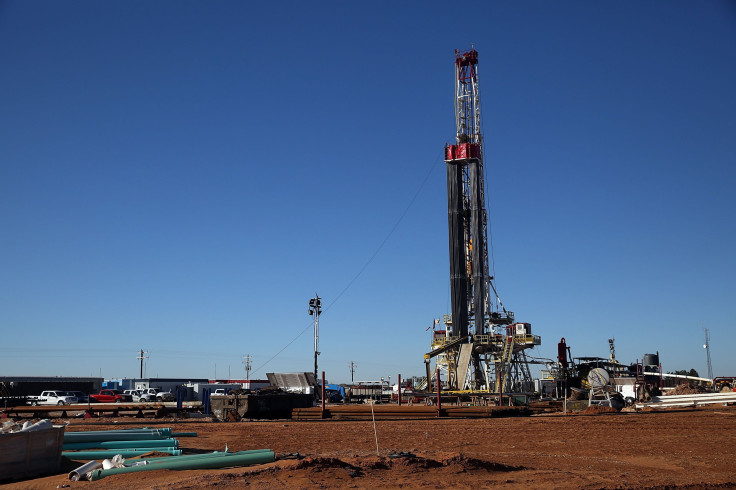

Spurred by the rise of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, the oil-and-gas boom in the U.S. means the country is producing and burning rising amounts of natural gas, which is 80 percent methane. Emissions are expected to climb in coming decades unless checked, posing a near-term threat to the planet, federal regulators have warned.

Here are five things you need to know about methane emissions.

More Potent Than CO2

Methane, or CH4, has a shorter life span than carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. While CO2 molecules can linger for hundreds or thousands of years — trapping heat and causing global warming — methane emissions last only about 12 years.

But methane is as much as 84 times more potent than carbon is over a 20-year period, said David Lyon, a scientist with the Environmental Defense Fund in Austin, Texas. In that way, methane is like a splash of lighter fluid, instantly amplifying the heat and accelerating warming.

This causes a chain reaction. With the warming of the planet, the vast expanse of permafrost in areas such as the American Alaska and the Russian Siberia is beginning to thaw, releasing huge stores of methane and carbon dioxide and, again, raising the planet’s temperatures. That means all the effects of climate change — from sea level rise and severe storms to aggressive droughts and frequent heat waves — will happen faster than they would have done without methane, Lyon said.

In 2015, the global average temperature rose by 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) above the preindustrial average, NASA reported in January. At the U.N. climate change talks in Paris, world leaders agreed to limit warming to 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit).

“It’s critical to reduce methane emissions to stop warming in the short term, since there could be a tipping point in the climate,” Lyon said. “If things like sea level rise happen quickly, it’s going to be much harder to move people away from areas that would get inundated.”

America’s Methane Makers

The amount of methane in the atmosphere has jumped more than 150 percent globally since the U.S. became a country, the U.N. climate science panel has estimated.

About 30 percent of U.S. methane emissions come from the oil-and-gas industry, including wells, refineries, pipelines, processing plants and storage facilities.

In fracking operations, small amounts of natural gas often rise to the surface alongside crude. Many companies have found it cheaper and easier to simply burn, or flare, the gas, which produces methane emissions. Other times, operators intentionally vent or accidentally leak the excess gas from well sites and pipelines. Faulty equipment and leaky systems cause more than 8 million metric tons of unburned methane to seep into the atmosphere each year, which the Obama administration has estimated is the climate equivalent of running 180 coal-fired power plants.

Another 26 percent of U.S. methane emissions comes from so-called enteric fermentation, or cow farts. Industrialized livestock operations have created a surge in waste and gases from beef cattle and dairy cattle, as well as, to lesser extents, horses, pigs and sheep. Garbage landfills are the third-largest source of U.S methane, followed by coal mining, livestock manure and other smaller sources.

Calamity in California

On top of regular industrial emissions, the methane arena recently got a massive boost from a four-month-long leak in Southern California.

The Aliso Canyon natural gas storage facility released more than 100,000 tons of methane from Oct. 23, when the leak was first reported, to Feb. 11, when Southern California Gas Co. said it plugged the flow of gas. The accident caused the largest release of methane in U.S. history, scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the University of California at Davis and other partners found in a Feb. 25 study.

The Environmental Defense Fund’s Lyon said it’s unclear how the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency will account for the Aliso Canyon leak in its annual greenhouse gas inventory report. The agency currently doesn’t have a category for large one-off events like this, although officials are seeking advice on how and where to include those emissions.

The California event would add about 1 percent to the EPA’s inventory of oil-and-gas industry methane emissions, Lyon said.

What the U.S. Is Doing

The Obama administration set its first methane-related target in January 2015. The White House committed to cutting oil-and-gas industry emissions by as much as 45 percent within a decade, the same target Obama and Trudeau announced Thursday.

The EPA in August proposed what it called “common sense” measures to cut methane emissions from new and modified oil-and-gas wells and facilities. Its proposal would require operators to find and repair leaks, capture natural gas from completed fracking operations and limit emissions from related infrastructure, including pneumatic pumps, gas transmission stations and compressors.

The U.S. Interior Department in January added another layer by targeting oil-and-gas wells drilled on federal and tribal lands. Its proposal would overhaul 30-year-old regulations and require operators to use existing technologies to limit flaring at oil wells, to regularly check for natural gas leaks and to replace outdated equipment that allows large volumes of gas and methane to escape into the air. About one-quarter of the country’s shale oil-and-gas deposits reside under federal and tribal lands.

As part of Obama’s latest announcement, the EPA said Thursday it will start devising regulations for existing wells, which account for 90 percent of the industry’s methane emissions. The agency aims to release draft requirements in April for companies to provide information about the equipment and technologies they could use to reduce methane leaks.

Pushback Could Be Coming

The administration’s proposals likely won’t be finalized or put into action until after Obama leaves office next January. If a Democrat wins the White House this fall, the measures will likely stay on track, as both candidates for the party’s nomination, U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton have vowed to uphold Obama’s legacy on climate change. In contrast, Republican candidates have promised to dismantle a slew of EPA restrictions and aren’t expected to usher in methane rules.

Obama’s methane proposals face substantial pushback from the American oil-and-gas industry, which has argued new rules are unnecessary, since companies are cutting emissions voluntarily. U.S. methane emissions fell by nearly 15 percent between 1990 and 2013, thanks largely to reductions in the oil-and-gas industry, the EPA said, although regulators estimated emissions would rise 25 percent this decade unless they are checked.

“Additional regulations on methane by the administration could discourage the shale energy revolution that has helped America lead the world in reducing emissions while significantly lowering the costs of energy to consumers,” Kyle Isakower, vice president of regulatory and economic policy at the American Petroleum Institute, a leading industry group, said in an emailed statement Thursday. “The administration is catering to environmental extremists at the expense of American consumers.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.