Police Shooting Statistics Show Black Police Officers Don't Help Stop Killings: Why Real Diversity, Not Tokenism, Matters

High-profile killings of black males by police in 2014 fueled the Black Lives Matter social justice movement, nationwide protests and a debate over how police forces should operate – and what they should look like.

When Darren Wilson killed 18-year-old Michael Brown in 2014, the 53-member Ferguson, Missouri, police department had just three black officers. The city of Ferguson, however, is two-thirds black. Police reform activists were quick to point out the discrepancy and champion a solution that could help address the fact that black men are three times more likely than white men to be killed by police: increase diversity in police ranks.

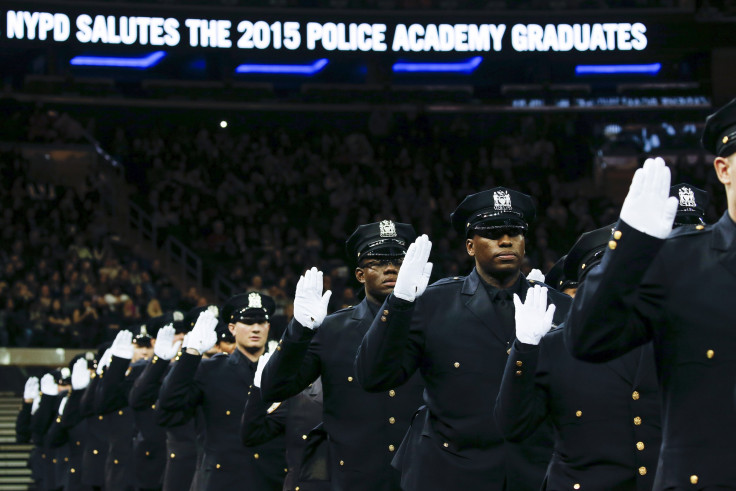

At around the same time, journalists and activists began building the first comprehensive databases of police killings in the U.S. Now, using that data, researchers have shown that making police forces more diverse might not reduce police killings of black people -- unless police departments can increase their number of black officers to a “critical mass," or roughly 35 to 40 percent of the total force.

That level of representation moves beyond token hiring and represents a change in the culture of a department. Below that level, data shows that more black officers can actually increase the rate of lethal encounters with black citizens, says a new study that will be published next month in the Public Administration Review.

“In places like Ferguson, where blacks are only 11 percent of the police force, efforts to double or even triple the share of the police force that is black… may actually increase violent interactions between police and black citizens until the critical mass is achieved,” write the study’s authors, a team from Indiana University.

Research has been mixed on whether black officers are more or less likely to use force than white officers toward black suspects, said Sean Nicholson-Crotty, the study’s lead author. But those mixed results may be explained by differences in how any outnumbered group tends to behave in a bureaucracy.

When there are just a few members of an outsider group in a bureaucracy, they tend to be the ones who most forcefully push the norms and culture of the bureaucracy to prove they belong. But when that outside group becomes large enough, they tend to influence the group, not the other way around.

“Once you get up to a certain density of the organization that looks like you... you expect that a big enough group in the organization share your values and your expectations,” Nicholson-Crotty told the International Business Times. “You can behave differently.”

This critical mass concept was first shown in early research on women in the corporate workforce, Nicholson-Crotty said.

Researchers examined the 100 largest police departments in the country and used data from the Washington Post’s Fatal Force project, which found that police shot and killed 963 people (233 of them black) in 2016, and 991 (258 of them black) in 2015.

The study also used data from the Mapping Police Violence project, which counted over 800 people killed by police in 2016 (289 of them were black) and 1,207 people killed by police in 2015 (346 of them black).

The research team behind the study tried to control for both the number and percent of black residents, Nicholson-Crotty said. They found that one of the strongest indicator of how many black people a department killed was how many white people it killed.

“There’s just some police departments that use lethal force more than others,” Nicholson-Crotty said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.