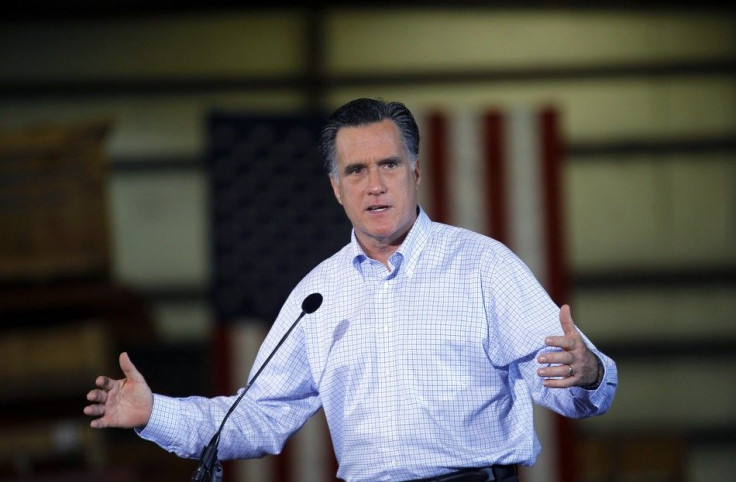

Romney Education Plan: More School Choice, Gut No Child Left Behind

The education agenda Mitt Romney unveiled during Wednesday's speech to the Latino Forum and an accompanying policy paper appears similar to the Obama administration's policy in many ways, but there are a few key differences.

Romney vowed to bolster parental choice in an unprecedented way, embracing a longstanding Republican line. President Barack Obama has also pushed to give parents more options by encouraging states to expand charter schools. The president has angered teachers' unions in the process, undercutting Romney's repeated assertions that he is too in thrall to union campaign money to enact meaningful reforms.

But Romney would go further, stressing the sort of free-market approach that underlies most of his policies. His plan would reshape how federal money flows to low-income and special needs students. Under the current formula, states and districts receive money based on the number of low-income and special education students they have, an outgrowth of the 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act's focus on helping the disadvantaged.

Romney would change that by having those federal dollars follow individual students rather than districts. With that money in hand, low-income and special needs students would then be able to choose any school in their state: public, charter or, in states where it's allowed, private.

The idea is to encourage robust competition in the education market. Schools would vie for those students and the federal money they represent, the rationale goes, and families would be able to shop around for the best option.

By pushing that free-market scenario, Romney also threw his weight behind the polarizing idea of offering students school vouchers. Republicans have traditionally supported offering vouchers and bolstering student choice, while Democrats have warned that they undercut public education (it's analagous to the furious debate over Wisconsin Republican Paul Ryan's Medicare reform plan, which would give seniors money with which to purchase private insurance).

Lest there be any doubt about his stance on vouchers, Romney also attacked Obama for eliminating the District of Columbia's Opportunity Scholarship Program, which gave low-income students vouchers to put toward private schools. The program produced mixed results -- a Department of Education study found that it had no effect on test scores, although it increased graduation rates for enrolled students -- but congressional Republicans rallied behind it and denounced Obama's decision to discontinue the program.

Romney's plan also axes the central enforcement mechanism contained in No Child Left Behind, George W. Bush's 2001 education overhaul that has fallen out of disfavor a decade after it attracted bipartisan support in Congress. No Child Left Behind fortified the federal government's role in education by requiring schools to demonstrate regular progress on student test scores; federally funded schools that fell short faced penalties that included being forced to fire teachers.

While Romney has offered qualified praise for No Child Left Behind, saying in the policy paper that because of the law standards, assessments, and data systems are light-years ahead of where they were, his plan would roll back the federal government's role, instead requiring states to evaluate schools and districts with publicly available report cards that assign an A through F letter grade.

In keeping with the same theme of reducing the federal role, Romney would expand the private sector's role in financing college education. That represents a reversal from the Obama administration's decision to allow students to borrow directly from the government, eliminating the fees that went to banks and other financial institutions that acted as middlemen.

The policy paper also takes on Obama's moves to increase Pell Grant funding, arguing that flooding colleges with federal dollars only serves to drive tuition higher and saying that Romney would refocus Pell Grant dollars on the students that need them the most, suggesting that a Romney administration could restrict the number of students who are eligible for the grants.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.