Scientists Capture Footage Proving These Tiny Critters Are Master Acrobats

KEY POINTS

- Springtails in lab pools made a successful landing on their feet in about 85% of the cases

- Springtails are record holders of orienting while landing faster than any other animal tested

- A small robot mimicking springtail's jump had a 75% landing success

These small, tiny insect cousins could give tough competition to Simone Biles. For the longest time, the somersaults performed by these critters called springtails appeared random and chaotic. A new study has now found there is more to these jumps than meets the eye.

Springtails "are famous because they know how to jump but also famous because they have no control at all according to the literature," biomechanist Victor M. Ortega-Jiménez of the University of Maine in Orono, said, reported ScienceNews.

Ortega-Jiménez and his colleagues challenged this idea in their paper, published on Nov. 7 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. High-speed videos were recorded of the springtails in action.

It was found springtails in lab pools made a successful landing on their feet in about 85% of the cases. Researchers then designed a small robot mimicking springtail's jump, and it had a 75% landing success.

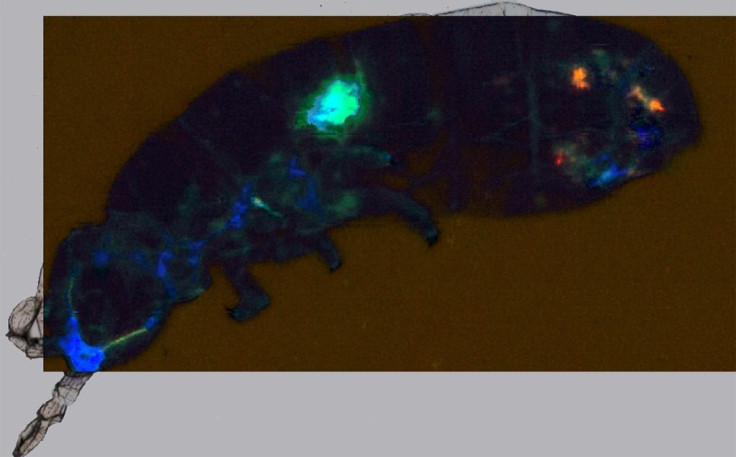

The springtail species Isotomurus retardatus was filmed at fast speeds of 10,000 frames per second, which showed there was a method to this madness.

It was found these wingless creatures curl their bodies during flight, much like cats, but only faster.

Ortega-Jiménez said springtails are record holders of orienting, while landing faster than any other animal tested, at less than about 20 milliseconds.

There are more than 3,000 springtail species that do not harm humans, and these acrobats are often ignored.

Springtails "are not only cute and interesting to look at; they are also among the most numerous and functionally important animals on our planet," Anton Potapov, a soil animal ecologist at the University of Göttingen in Germany, and who was not involved in the study, commented

"You can find them virtually everywhere, and they contribute to so many ecosystem processes," Potapov added.

To achieve these master jumps, springtails take the help of two of their body parts. One is a long, hinged thumper called a furcula, present underneath the body. The other is a short wide tubular organ called a collophore that is visible on the abdomen.

Springtails use the furcula to smack the surface beneath them, launching themselves into the air. Some springtail species have been known to jump at speeds of 280 times their body length per second.

For the landing, the collophore comes into use. A bit of water in the collophore gives it some weight that keeps the semiaquatic animal from bouncing into somersaults as it lands.

Another critter thought to be extinct for 80 years has been rediscovered. The large, wingless, wood-eating cockroach, Panesthia lata, is unique to Australia's Lord Howe Island.

"The survival is great news, as it has been more than 80 years since it was last seen," said Lord Howe Island Board Chair Atticus Fleming about the find, first made in July 2022. "Lord Howe Island really is a spectacular place, it's older than the Galápagos islands and is home to 1,600 native invertebrate species, half of which are found nowhere else in the world."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.