Trump Muslim Ban And FDR's Japanese Internment Camps: How Anti-Islam Debate Compares To Roosevelt's WWII Policies

When critics began condemning Republican presidential front-runner Donald Trump this week for proposing a ban on Muslims entering the United States, he cited what he portrayed as a relevant historical precedent: World War II and the trio of proclamations issued by then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt empowering the authorities to apprehend and detain Japanese, German and Italian immigrants. In 1942, Roosevelt delivered an executive order that sent Japanese-Americans — many of them families that had been settled in the United States for generations — to so-called internment camps established along the West Coast.

Trump described Roosevelt's policies as "far worse," but history experts have suggested the former president's wartime decisions weren't a good example for Trump to use at all. While Americans initially backed Japanese-American internment camps, the policy was later proclaimed a human rights violation and a dark period in U.S. history.

Within 50 years of Roosevelt's announcement, the government had formally apologized for the internment and paid out reparations to survivors. A federal study in the 1980s found "no justification in military necessity" for the program, which it said was caused by "race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership." Even today, a document in Roosevelt's presidential library notes that the choice to intern Americans is seen as "a blemish on Roosevelt’s wartime record."

"The thing that's striking about Trump's invoking Roosevelt is most people now consider it was a serious mistake on the president's part," said Matthew Evangelista, a history and political science professor at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

Trump's comments calling for a shutdown of Muslim immigration "until our country's representatives can figure out what is going on" came days after a Muslim couple fatally shot 14 people and injured 21 in San Bernardino, California. Similarly, Evangelista said, Roosevelt's orders came after the Pearl Harbor bombing that killed 2,403 and wounded 1,178 on Dec. 7, 1941. At the time, the U.S. was engaged in a formal war.

That day, Roosevelt, receiving advice from several military sources, signed Presidential Proclamation No. 2525, which said all non-naturalized natives, citizens or subjects of Japan living in the U.S. could be apprehended and removed as alien enemies. He soon followed with No. 2526, which pertained to people from Germany, and No. 2527, for people from Italy. All the proclamations were in keeping with the Alien Enemies Act of 1798.

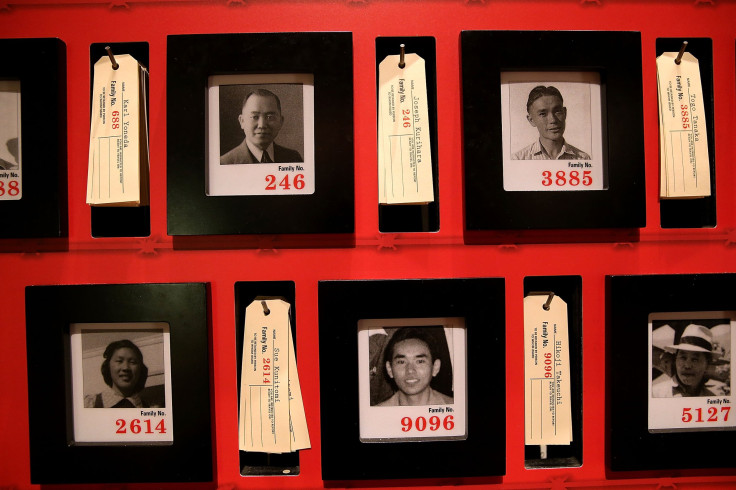

Then Roosevelt took it a step further, issuing Executive Order 9066, which allowed the Army to designate areas where any or all people could be removed. The Army took control of the West Coast and evicted more than 110,000 Japanese-Americans out of fear they were serving as spies for Japan, said Frank H. Wu, chancellor and dean of the University of California Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco. He added that the decision was "wildly popular at the time."

In 1942, a National Opinion Research Center survey found 93 percent of Americans backed the government's decision, according to a 2009 article in the journal American Behavioral Scientist. In 1944, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of internment in the case Korematsu v. United States.

"There were almost no defenders of Japanese-Americans, who were unpopular even before the war," said Wu, who co-wrote the textbook "Race, Rights and Reparation: Law and the Japanese Internment." "The thought was you'd be loyal to Japan even if you were born in the U.S., didn't speak Japanese, were Christian."

When the war ended and no such spies were found, Wu said the public began to walk back its position. In 1980, Congress directed the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians to study the internment program. It later concluded that "a grave personal injustice was done to the American citizens and resident aliens of Japanese ancestry who, without individual review or any probative evidence against them, were excluded, removed and detained by the United States during World War II."

In 1983, the Korematsu conviction was overturned in a lower court. Five years later, then-President Ronald Reagan signed an official apology and authorized a $20,000 payout to each survivor of the internment camps.

Now, terrorist attacks connected to the Islamic State group have renewed the debate over Roosevelt’s policies. After a Nov. 13 mass shooting in Paris that killed 130 people was linked to Islamic radicalism, some officials asked to close their borders to Syrian refugees. David Bowers, the mayor of Roanoke, Virginia, was among them.

"I'm reminded that Franklin D. Roosevelt felt compelled to sequester Japanese foreign nationals after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and it appears that the threat of harm to America from ISIS now is just as real and serious a threat as that from our enemies then," he wrote Nov. 18. Bowers later apologized for his comments.

Usually not one to sidestep controversy, Trump himself has tried to clarify his allusions to Roosevelt. The candidate said he was referencing Roosevelt's proclamations about removing nonresident enemies, not the executive order that eventually interned U.S. citizens. Trump told reporters Tuesday he hated the concept of internment.

“I am not proposing that,” Trump told MSNBC. “We're not talking about Japanese internment camps. No, not at all.”

But in some ways Trump’s remarks go further than Roosevelt’s wartime policies. Eric Muller, a law professor at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, noted that while the precedents set by Roosevelt make it legal for a president to take actions against nationals from enemy nations, Islam is not a country.

"He in a sense is saying we are at war with Islam, and therefore he wants to claim the authority to take action against anybody who is of Muslim faith," Muller said. "Those precedents, about Italian, German and Japanese aliens, they're not relevant to that."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.