Veterans Day 2015: A Vietnam Deserter In Canada, Decades After Fleeing US Army, Is Leading The Fight For Other US Military Deserters North Of The Border

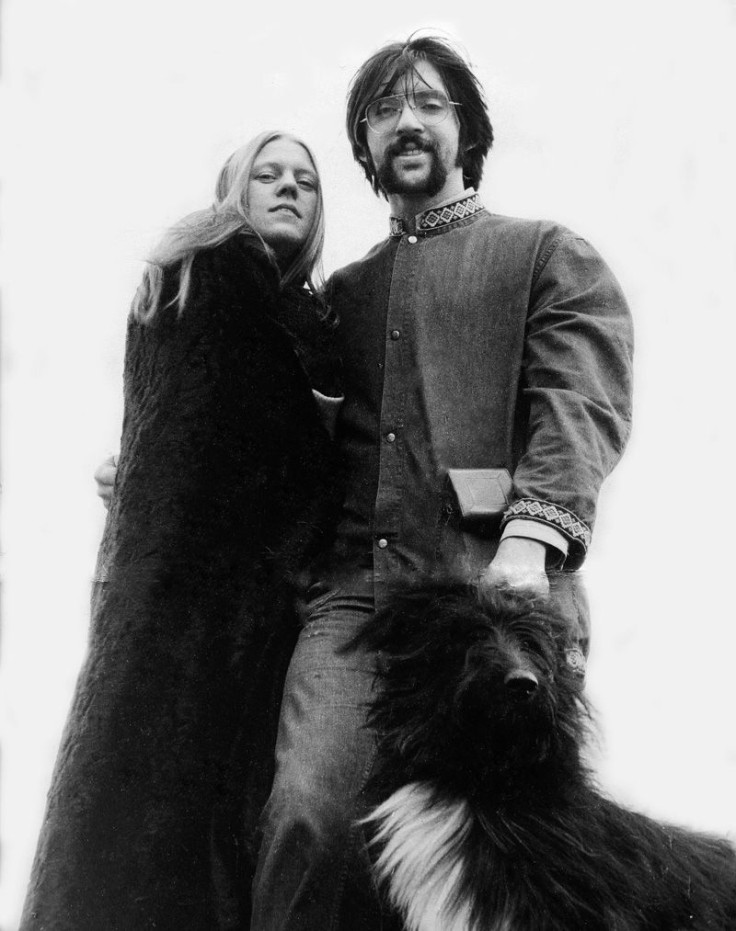

Facing the prospect of going to Vietnam to fight for his country back in October 1969, U.S. Army Spc. 4th class Bill King was given some sobering advice. “Just say your goodbyes, because you’re gone,” a senior Army officer told King, then 23. The possibility of never again seeing his wife, Kristine, who was just 19 at the time, gripped him within moments of receiving his deployment orders.

When he told Kristine, the newlywed couple chose a fate that would dramatically change their lives forever.

“We looked at each other and decided right there in the moment,” King recalled of the day when he was unexpectedly ordered to trade in his safe, comfortable life for one of combat in a war that had already claimed tens of thousands of U.S. lives. “She said to me, ‘Will you come with me?’ and I looked at her straight in the eyes and said, 'Let's go to Canada.'”

As the U.S. celebrates Veterans Day Wednesday, King’s story of decided desertion almost a half century ago is one that's shared with hundreds of Army draftees, recruits and volunteers over the years, avoiding Vietnam as well as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Canada had for years allowed a place of refuge for the former U.S. servicemen, but the country's Conservative government has spent the last decade working to return them to the States, threatening to disrupt King's work of helping the newest generation of U.S. military deserters settle in Canada. But now, a recent change in Canadian government has provided them a fresh sense of hope that deportation orders would be lifted once and for all.

A New Life

King hadn't come to the Army willingly to begin with. He'd dodged the draft and was living a pretty thrilling lifestyle, by his account. “I was playing with Janis Joplin and I was a music director,” he said this week from his home in Toronto. “We were playing in Memphis in Christmas 1968 and I decided to go home and see my parents because I hadn’t seen them in a few years and I was also a little disillusioned working with Janis. There was too many hard drugs for me.”

But when King got home to Jefferson, Indiana, he was met with the unexpected: His father had cut a deal with the FBI that would drop all charges for draft evasion if he returned to the Army. King was allowed to stay home for two weeks before setting off for basic training at a base in Kentucky, where he took up the job of base pianist. “I met a lot of people that way, a lot of officers and soldiers. When we spoke about Vietnam, the answer was unanimous. They all said, 'Don’t go to Vietnam'.”

He was moved to the Fort Dix base in New Jersey within a few months, and his orders of deployment quickly followed.

King tried applying as a conscientious objector, hoping to get discharged on compassionate grounds or get permission to serve his Army time anywhere outside of Vietnam. When he was denied, Canada quickly became one of the few options he had to get out of a war he resented from the start.

“It was the weight of taking someone else’s life and the sense that we were being used by Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew,” said King, referencing the U.S. president and vice president, respectively, at the time.

In turn, King and his bride fled into the nearby woods next to the base and hitchhiked up to New York City to stay with friends before thumbing rides in first a sauerkraut delivery truck to upstate New York and then to the Canadian border with a convict and his 14-year-old girlfriend, King recalled. “They arrested those two but let us across,” he said. “We had $95 between the two of us and we just started from scratch.”

While an arrest warrant was issued for King's desertion, he returned to the U.S. in 1976 after Jimmy Carter announced amnesty for all draft dodgers. As a result, he was generally discharged from the U.S. Army and the arrest warrant deactivated. It meant he could visit the family he left behind in the U.S. and take his Canadian-born son to see them.

A New Generation

In the intervening years, King played in bands in the Toronto area and became the creative director of the Toronto Jazz Festival in the late 1980s. However, the invasion of Iraq in 2003 cast King's mind back to the '60s and '70s. “I was ready for the deserters when they started coming in 2004 and I saw my main role as someone who just needed to be there for them," he said. "I've been in their shoes and had the same questions and anxieties they had."

As U.S. military personnel began coming across the border looking to avoid further service, King teamed up with Michelle Robidoux, a spokesperson for the War Resisters Support Campaign in Canada, to help them navigate the country's legal system. “Bill has played a very important role,” said Robidoux. “He was one of the first Vietnam War resisters to come forward and help the new generation to help them claim asylum and stay in Canada.”

King noticed a distinct contrast from his own experience as a military deserter and the new group: Many deserters from the Vietnam era had never seen combat, whereas the couple of hundred fleeing after serving in Iraq and Afghanistan were likely suffering from PTSD and other undiagnosed mental disorders, said King. “It was also much harder for them to stand up to the violence in the way we did. They didn’t have the split in the U.S. that we had, because [the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were] very stage-managed and really shut out the possibility of having a major anti-war movement,” he said.

While around 180 U.S. war deserters from the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts have either been deported or voluntarily gone back to the U.S., each facing a court martial and certain jail sentences, there is a core group of about 20 who remain in Canada as their deportation cases slowly wind through the Canadian legal system.

One such person is Joshua Key, who fled to Canada in 2005 after a tour of duty in Iraq. His decision was made the moment he witnessed a young girl gunned down on a street in Ramadi. "I started questioning everything," Key, who now lives in Canada and is being sought by U.S. authorities, said over the phone. “We used to have conversations and everyone would have their own reason for [staying]. But I don’t think there would be anyone who wouldn’t have thought of going AWOL, even if it was just... for a minute.”

After spending more than a year on the run inside the U.S., going from city to city and job to job, Key decided that Canada was his only hope of getting the law off his back. “I knew that it was either move to another place in the States and have to do that same stuff a year later, or move north,” he said recently during a phone call from his home in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Getting into Canada was easy, but supporting his family proved difficult, leading to a divorce, and his wife and children moving back to Oklahoma. Key’s life since has been fragmented. He has moved from place to place -- Ontario, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba. He has remarried and had three more children, and is allowed to remain in Canada while his battle against a deportation order works its way through the courts. He is not allowed to legally work (he supports himself with odd jobs) and cannot travel to the U.S., where he would face a prison sentence of up to 20 years, his lawyer said.

But with the newly installed Liberal Party government, there's hope for Key and the remaining war deserters. Taking power in Ottawa after a decade of Conservative rule, the party has supported the new generation of war deserters since they arrived in the country.

For King, who's working on drafting a letter with the War Resisters group to ask the new Canadian government to drop all legal challenges against the deserters, the changing political landscape in Canada isn’t just an opportunity for the likes of Key, but a stark reminder of King's similar past when he first sought refuge in the country under current Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s father, Pierre.

“[Justin Trudeau] has the charisma to make Canada a place of peace, progression and tolerance once again, and I really hope that the new war resisters can find a permanent home here.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.