'Whiplash' Is The Best Homoerotic S&M Film About Jazz Drumming You'll See This Year

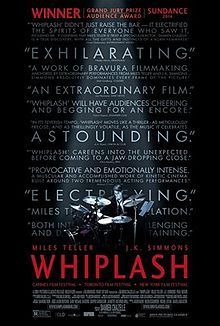

When "Whiplash" opens, 19-year-old Andrew Neiman (Miles Teller, "The Spectacular Now," "Divergent," and "21 & Over"), an aspiring jazz drummer who has just started at the prestigious Shaffer Conservatory of Music in Manhattan, sits in a dark practice room beating away at his drum kit. Suddenly, Shaffer’s famed music teacher, Terence Fletcher (J.K. Simmons, "The Closer," "Spider-Man," "Juno") shows up in a doorway after listening to him and invites Andrew to work with his studio band the next morning.

It doesn’t take long for the viewer to realize that “Whiplash” (which opened in wide release Oct. 23) is not going to be a fuzzy feel-good flick exploring the heartwarming relationship between mentor and student. At studio practice the next morning with his handpicked band, Fletcher tricks his new student into believing that he thinks Andrew is “the next Buddy Rich,” referring to Andrew’s favorite flashy jazz drummer. When Andrew fails to drum to the teacher’s preferred tempo, Fletcher hurls a drum kit at Andrew’s head, slaps him and mocks him as he weeps.

“If you deliberately sabotage my band,” he growls, “I will gut you like a pig. You are a worthless pansy who is now weeping and slobbering over my drum set like a 9-year old girl.”

It’s no wonder the film was dubbed “Full Metal Juilliard” by Sundance audiences, referring to the 1987 Vietnam War film "Full Metal Jacket" directed by Stanley Kubrick that explored the dehumanization of soldiers during boot camp. Written and directed by 29-year-old Damien Chazelle, who was inspired by his own experiences in high school with a demented music teacher, “Whiplash” shows Fletcher brutalizing Andrew, and even more painfully, Andrew’s own masochistic self-punishment.

Who knew that a movie about jazz drumming could be more thrilling and terrifying than most CGI action films or horror flicks?

Is Fletcher insane, or merely misguided? Does greatness require punishing discipline and a different set of near-inhuman rules that separate geniuses from the merely good? Is it ever worth sacrificing everything to create something beautiful? Although these are the film’s moral questions, what makes “Whiplash” interesting is not its answer to those questions one way or the other but rather the amazing cinematic ride it takes its viewer on while fleshing the questions out in film form.

“Whiplash” is as beautifully shot and edited as it is acted. When it becomes clear that Andrew is prepared to sign his pact with the Devil, in the form of the increasingly Satanic-looking Fletcher, and we watch him try to “play faster” to satisfy his teacher, frenzied edits that intercut shots of his pained face, bleeding fingers and then sweat shimmering on his cymbals help us to visualize the music and the passion of its player.

“Whiplash” could be interpreted as romanticizing the brutality that Fletcher inflicts upon Andrew. It could also be interpreted as indulging in Fletcher's machismo and homophobia. But the film is much more complex than that, and its representation of those themes is not its endorsement of them.

If anything, “Whiplash” explores the eroticism of male bonding. The film, which takes place in the intensely male space of the music conservatory, seems to depict a world without women. Andrew’s mother left the family when he was young, and he quickly dispatches with a new girlfriend because he doesn’t want her getting in the way of his desire “to be great.” No wonder Fletcher constantly hurls homophobic epithets at his students; homoeroticism threatens their male world at every turn.

Andrew is also caught in an Oedipal drama with two fathers. Should he identify with his nice guy father, a failed writer, played by Paul Reiser? Or will he join the dark side with Terence Fletcher? In an incredible scene in which Andrew, after a falling out with Fletcher, sneaks into a jazz club to watch his teacher play jazz piano, the expression on his face toggles between love, longing and confusion in a way that makes the viewer forget for a moment that “Whiplash” isn’t a love story. But it is, in a way. It’s also a horror film in the vein of Darren Aronofsky’s dark and expressionistic “Black Swan,” which was about an aspiring ballerina (played by Natalie Portman), who takes her artistic ambitions to a suicidal level of recklessness and intensity.

If you’re looking for a feel-good, sentimental film about the student/mentor relationship a la “Dead Poets Society,” you've got the wrong film. The dark, gripping and unpredictable Sundance hit “Whiplash” will keep you as off-kilter as the syncopated jazz drum beat that leads its audience toward the film’s electrifying and surprise ending.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.