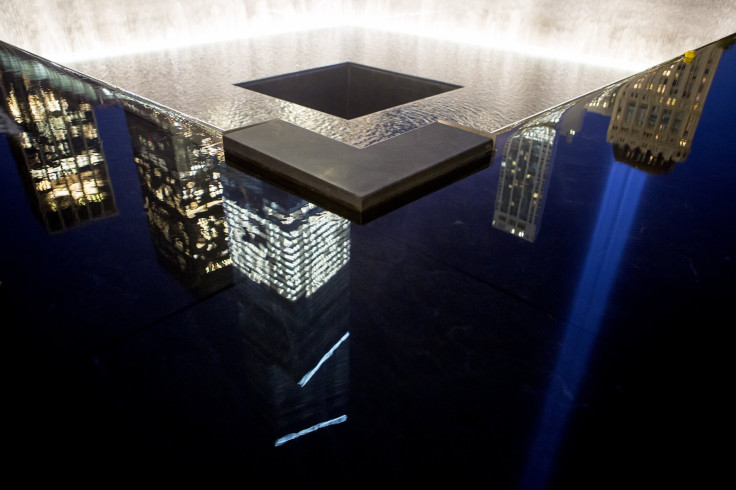

9/11 In The Age Of ISIS: Facing Continued Anti-Islam Sentiment, American Muslims Are Determined To Reclaim The Narrative

“Terrorist! Go back to your country, Bin Laden!” Those were the words Inderjit Singh Mukker heard as an assailant brutally attacked him in his car in a Chicago suburb Tuesday night, according to reports from the Sikh Coalition, an advocacy group. While the victim, who wore a turban as a marker of his Sikh faith, wasn’t Muslim, it’s doubtful his attacker understood the difference between Sikhs and those who practice Islam.

The incident occurred just three days before the 14th anniversary of the September 11 attacks, and experts say it’s another troubling example of a country that is still grappling with pockets of prejudice and violence against Muslim Americans, or even those who are assumed to be Muslim. And while Muslim advocates say the community has come a long way in educating the public and working to dismantle the stigma and prejudices against it, events of the last year -- including the rise of ISIS and graphic media stories of its brutality -- have stoked the very flames of Islamophobia that the community has worked so hard to quell over the past 14 years.

“The shadow of 9/11 looms large on the discourse, on domestic and foreign policy, on the narrative,” said Wajahat Ali, co-author of “Fear Inc: The Roots of the Islamophobia Network in America” and an Al Jazeera America journalist who writes frequently about Muslims in America. “The usual stereotypes were transformed into a civilizational conflict: Islam vs. the West. And that’s been invigorated by the sensationalistic acts of ISIS and the very deliberate manipulation of fear against Muslims by politicians trying to raise money.”

A Most Violent Year

Indeed, since the last anniversary of 9/11, the American Muslim community has faced a tumultuous 12 months. In February, when three young Muslims were shot and killed in their home in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, over what police said was a “parking dispute,” it unleashed a media firestorm. Critics called for an investigation of the incident as a hate crime. The FBI still hasn’t ruled out religious bias as a motive.

In May, demonstrators protested outside a Phoenix mosque, claiming that Islam was a religion of violence. Several gun store owners across the South have declared their shops “Muslim-free zones” -- moves that have been challenged by the American Muslim groups on grounds of civil liberty violations. It’s no coincidence, experts say, that such events have occurred during a year when the violent acts of ISIS abroad have been constantly in the news.

“ISIS has been a really interesting inflection point for Islamophobes as a bargaining chip for people who might not otherwise agree with them,” said Samar Kaukab, executive director of a program that focuses on complex research initiatives at the University of Chicago and a frequent writer and speaker on Islam and feminism. “When we see the brutality of ISIS, beheadings, aid workers being killed, I think some Americans who don’t know how to make sense of that start to buy into the Islamophobes’ arguments.”

The regime’s rise has been a clarion call for American Muslims to go beyond the interfaith work that has been so common in the years since Sept. 11, 2001. For many Muslims, that was exemplified by the debate over the religious bona fides of ISIS in intellectual and media circles earlier this year. While President Obama declared the group to be “not Islamic,” a lengthy article in the Atlantic countered that “the reality is that the Islamic State is Islamic. Very Islamic.” What ensued was a heated debate in the media over whether ISIS represented an accurate interpretation of Islam.

“In the early years post-9/11, we could get away with slogans like ‘Islam means peace,’ -- very simplistic statements,” said Kaukab. “That worked effectively at that point, but we’re in a very different era now, and these simple slogans aren’t going to cut it. We really need to understand what we think and explain it to others. If we’re really honest with ourselves, we as American Muslims are struggling to answer and explain questions about this political interpretation of Islam.”

She added that Muslims need to know how to respond when they see the behaviors and actions of ISIS being linked to a mainstream theological understanding of Islam. “We need people who have a strong grasp on complexity and have better, more nuanced talking points,” she said.

Reclaiming The Narrative

Still, many activists say that the community has come a long way in effectively responding to anti-Muslim rhetoric.

“If you look at the things that have happened in the last year, you see the anti-Muslim sentiment leaking from the Internet into the real world,” said Shahed Amanullah, the founder of an accelerator that works with startups focusing a positive social impact on Muslim communities. “But we’re finding that there’s resilience both in the American Muslim landscape and in the rest of America itself. Sept. 11 helped American Muslims realize that Muslims need to be more integrated and more proactive. As a result, there’s a confidence I see among American Muslim communities that comes from more than a decade of realizing what works when it comes to making progress.”

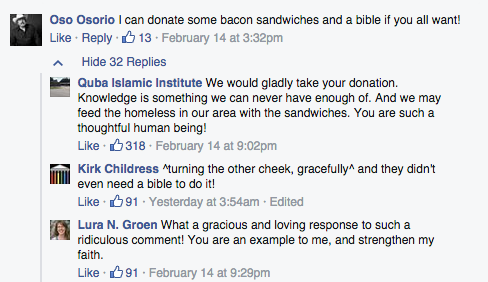

Amanullah points to the incident in Phoenix, when mosque organizers invited protesters into the mosque and organized a peaceful response. Another example of a smart response, said Amanullah, is when a Houston mosque was burned down by suspected arsonists. The Quba Islamic Institute posted information about the incident on its Facebook page -- which quickly drew hateful comments.

“But the group responded to these comments in ways that actually went viral,” said Amanullah. “That’s the paradox. You’re seeing these positive expressions of Muslim communities, but coming in the face of the worst violence against Muslims since 9/11. The hatred online is so strong, and it’s starting to spill out to the real world. But the real world is different from the online space.”

Ali says American Muslims have been inspired by the collective pain of 9/11 to be more proactive in reclaiming the narrative for themselves. “We see more lawyers, more elected officials, more Mulsims on TV and behind the scenes, more Muslims reclaiming both their Muslim and American identities -- that one is not in conflict with the other,” said Ali. But the community needs to continue to do more -- and find more ways to tell Americans who American Muslims are.

“The core reasons for Islamophobia in America are ignorance and the fact that most Americans don’t think they know a Muslim,” said Ali. “If most people don’t know a Muslim, that’s tragic. It’s on us to fill the vacuum and tell our stories -- with the pen, the mic, the gavel, the stethoscope, whatever ways we can.”

Mansoor Shams, a Marine who served from 2000 to 2008, says he’s been working to tell his story online, but he was shocked by the level of vitriol when he became active on social media -- and added that his military service hasn’t always been a shield against it.

“I didn’t realize how much hate was out there toward Muslims until I got on Twitter. People might seem OK in real life, but there are thousands of people hiding behind their keyboards and computer screens spreading tremendous amounts of hate,” said Shams. He has been asked what he deems bizarre questions -- like whether he would shoot another Muslim if he were in combat in a country like Iraq, or whether he supports regimes like Hamas and Hezbollah.

#TheOneLineYouHateMost "Muslims are Marines too?" Ahh yeah. pic.twitter.com/7v76l7g9qA

— MuslimMarine (@mansoortshams) September 7, 2015“I always respond that I would always fulfill my duty, my responsibility. If there was another Marine being hurt in the field, of course, my job would be to do anything to save him. As a Marine, our motto is God, Country, Corps. It doesn’t say Christian god, or a Jewish god,” said Shams. “I’d give my life for this country. I don’t know how much more patriotic it gets than that.”

Shams added that it’s vital for American Muslims to understand their faith and learn how to speak smartly in defense of it. But what’s more important, he said, is for American Muslims to continue to play a positive role in their communities. He said the U.S. is a country struggling to understand Muslims, and the Muslim world, and the media doesn’t do a great job of helping them.

Shams’ favorite tradition on Sept. 11 is to help organize Muslims for Life, a blood drive campaign through his Muslim religious community that collects 3,000 bags of blood each year on Sept. 11 in commemoration of the 3,000 lives that were lost in the attacks.

“That’s how we tell Americans,” he said, “that we Muslim Americans are just as American as anybody else.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.