British Financiers Getting Socked By UK Politicians, Central Bankers, Regulators

Past Few Days Has Seen a Barrage of Criticism, New Taxes, Unhelpful Predictions

If there is one thing the bankers, money managers, broker-dealers and other market-makers that make up what is collectively known as Wall Street never seem to worry about, it's whether they have the full support and backing of the United States government. While the man ostensibly in charge has sometimes used the bully pulpit to deliver populist rhetoric against the fat cats, people like Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner and Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke are legendary in their willingness to serve as Wall Street saviors: government officials with cash-stuffed pillow at the ready in case they are needed to cushion a big bank's fall.

Geithner's protective stance toward the banking sector is so openly acknowledged that many, even at the highest levels of government, seemed to believe he formerly worked for, and has many friends at, Goldman Sachs. Geithner never did. Bernanke's cut-the-rate-no-matter-what monetary policy has become such an accepted part of the economic landscape, it has inherited a slightly pejorative descriptor as a Bernanke put.

There used to be a time, too, when the bankers, money managers, broker-dealers and other market-makers in London that make up what is collectively known as the Square Mile felt the same way about their government. Not any more.

In the past few months, but particularly in the last few days, British government officials such as a deputy head of the Financial Services Authority, the British Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Governor of the Bank of England have become the bane of the English banking system's existence.

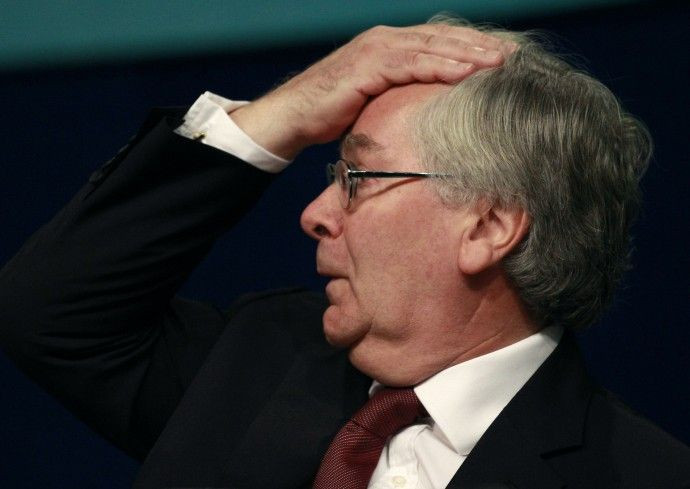

First there was Andrew Bailey, a deputy head in charge of UK banks at the aforementioned FSA, something akin to the American Securities and Exchange Commission, telling banks to assume the crash position in case the unthinkable -- a breakup of the euro common currency area -- ended up happening. That might have seemed like some overheated rhetoric until the Governor of the Bank of England, Sir Mervyn King, said basically the same thing in semi-apocalyptic testimony.

It was one thing for government officials to go around frightening the proverbial children and horses, but those comments were nothing compared to what they would say next. What really got the British financial cadre up in arms were suggestions by King, made public late last week, that bankers should look at curtailing their precious bonuses this year. That call, which banks more or less politely nodded at and dismissed, was reiterated Wednesday by Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne, calling current pay levels unacceptable. On top of that, Osborne is hitting some banks with a special tax.

The Bank of England began a two-day meeting today, in which, some financiers are hoping, the poor performance of the British economy will lead the bank towards a new round of quantitative easing, something that would flood liquidity into the credit markets and buoy equities.

Inasmuch as that represents waiting for the British government to do them a favor, with the recent developments, it might be wise for the moneymen of London to manage their expectations.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.