California Methane Leak: Here's Where Over 400 US Natural Gas Storage Facilities Are Located [MAP]

The California facility spewing massive amounts of natural gas is one of more than 400 storage sites across the United States. Underground wells from Alaska to New York store trillions of cubic feet of the fuel during the year, which utilities tap during chilly winters or power outages. Yet the quality of monitoring and upkeep varies from site to site, raising the risk that more storage facilities could sprout serious leaks in other states.

"It's only a matter of time before the next one happens," said Tim O'Connor, who directs the Environmental Defense Fund's oil and gas program in California. "We just haven't had the regulatory regimes needed to keep up with the dangers associated with it."

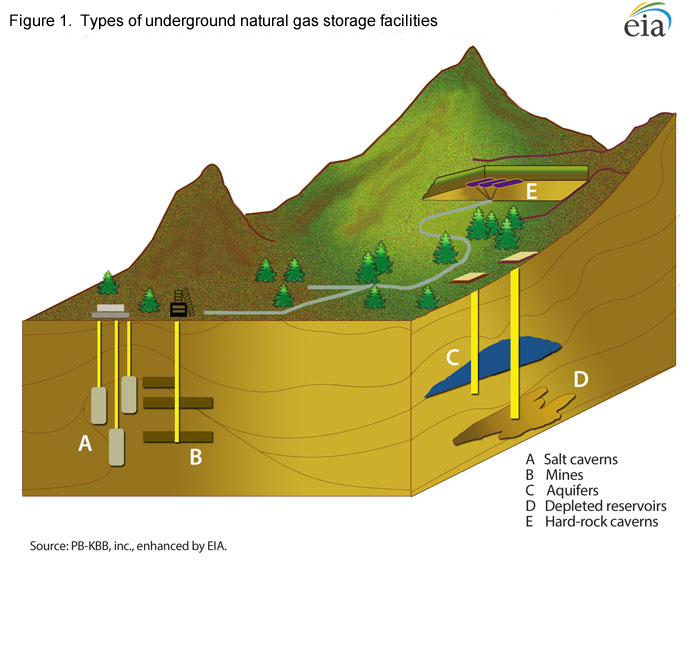

U.S. Underground Natural Gas Storage Sites

While federal regulators monitor natural gas storage sites to ensure utilities have enough supply to meet demand, state agencies are mostly in charge of inspecting and analyzing wells and ensuring equipment is up-to-date. Some states have tougher programs, including Texas and Kansas, which both experienced massive leaks before tightening and updating their regulations. California, on the other hand, hasn't revisited its rules in decades, O'Connor said.

"We see a totally unlevel playing field," he added.

Still, major accidents are fairly uncommon in the natural gas storage industry. Jose Villar, an underground storage analyst at the U.S. Energy Information Administration, said smaller leaks occasionally happen when utilities inject new supplies of gas into the sites or withdraw them during the chilly months to help heat buildings. "Generally speaking these facilities are quite safe," he said.

The Aliso Canyon site in Los Angeles County, which first ruptured Oct. 23, is releasing about 48,500 pounds of methane per hour, according to the latest estimates by the California Air Resources Board, a state regulatory agency. Natural gas is 80 percent methane, and the compound is dozens of times more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.

"The leak effectively doubles the emission rate for the entire Los Angeles Basin," Stephen Conley, a scientist at the University of California, Davis, said Jan. 7, after flying his pollution-detecting airplane over the storage facility. "On a global scale, this is big."

California Gov. Jerry Brown declared a state of emergency Jan. 6, after more than 2,000 residents in the nearby Porter Ranch neighborhood were forced to relocate. The facility has so far wasted nearly $13.3 million in gas by one count, a sum that continues to rise as utility crews struggle to contain the leak.

Southern California Gas Co., which owns and operates the well, said last week it started the fourth phase of drilling a nearly 8,000-foot-deep relief well to contain the runaway natural gas. The utility expects to finish the project between late February and late March, SoCalGas said in a Jan. 13 media update.

County supervisors, state lawmakers and environmental groups — like the Environmental Defense Fund — have called for tougher regulations and better oversight of natural gas storage facilities in light of the nearly 3-month-old leak. Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich, who represents the Porter Ranch area, said the leak "calls into question the efficacy of the state's regulatory system," the Los Angeles Times reported earlier this month.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.