Coronavirus Update: Survivor Plasma Shows 'Signals Of Efficacy' In More Than 35,000 Patients

KEY POINTS

- Many COVID-19 patients want to get their hands on plasma of recovered patients

- Recent study showed it had positive results in about 35,000 patients

- Studies are still needed to be made to prove that plasma treats coronavirus

There are strong hints that survivor plasma can help in fighting coronavirus infection although there is no solid proof about such particular capacity, researchers said.

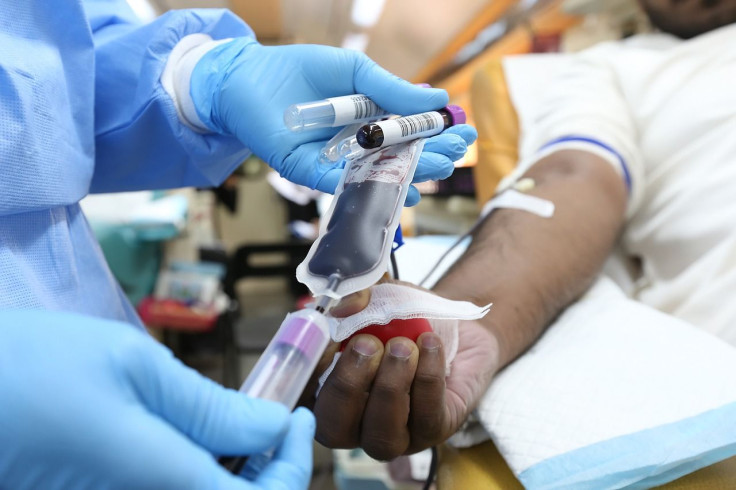

Mayo Clinic researchers say their study's findings suggest that blood plasma from recovered COVID-19 patients can help other victims, although they warn they have no solid proof. Despite this, however, others are seemingly in a mad rush to get their hands on the treatment, raising alarm among experts who say they still have to get a clear answer on whether or not such blood plasma can help. In the U.S., more than 64,000 COVID-19 patients already received convalescent plasma, Associated Press reported.

The practice of giving convalescent plasma to patients suffering from measles and flu is more than a hundred years old. This was the usual practice during those times when vaccines for measles and flu were not available yet. History proved that the treatment worked against some infections, although the results vary. It is still used as a tactic in modern times whenever new diseases emerge.

At present, there is no foolproof evidence that the plasma can fight coronavirus with high efficacy or as to how to best utilize it. However, initial data from around 35,000 coronavirus patients who received such treatment provide researchers what they call "signals of efficacy."

Mayo Clinic lead researcher Dr. Michael Joyner and his colleagues reported Friday fewer deaths occurred among patients who received plasma within three days after they tested positive for the virus. Researchers also report lesser deaths among those that received a convalescent plasma that contained high levels of virus-fighting antibodies.

The problem is that the work done by the researchers is not a formal study. For one, patients who received the plasma were treated in various ways in hospitals across the country as part of a program initiated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in an attempt to hasten access to experimental treatment.

The FDA program monitors what happens to plasma recipients involved in the program. However, those who run the program cannot say for certain that the plasma, and not some other treatment they also received, is the real reason why their condition improved.

At present, studies designed to establish this proof are currently ongoing across the country. Some of these studies seek to compare similar patients who were randomly assigned to receive plasma or a false infusion aside from receiving regular care.

Researchers of these particular studies, however, are having a difficult time in arriving at a conclusion as the virus rises and falls in different localities. Also, some patients directly asked for plasma instead of consenting to research that might have them infused with a placebo.

In the case of the research conducted by Mayo Clinic researchers, they already published their findings online ahead of a scientific peer review. Part of their findings shows that 20% of patients who received high-antibody plasma within three days after being diagnosed with the infection died within 30 days compared with 30% of patients later treated with low-antibody plasma.

The FDA, for its part, is closely looking at the evidence of such treatment. They might allow emergency use of convalescent plasma if the evidence looks good enough. FDA officials did not reply to requests for comment on the findings of the Mayo Clinic researchers.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.