NASA’s Study Of Pulsars, Neutron Stars Under Way With NICER Instrument

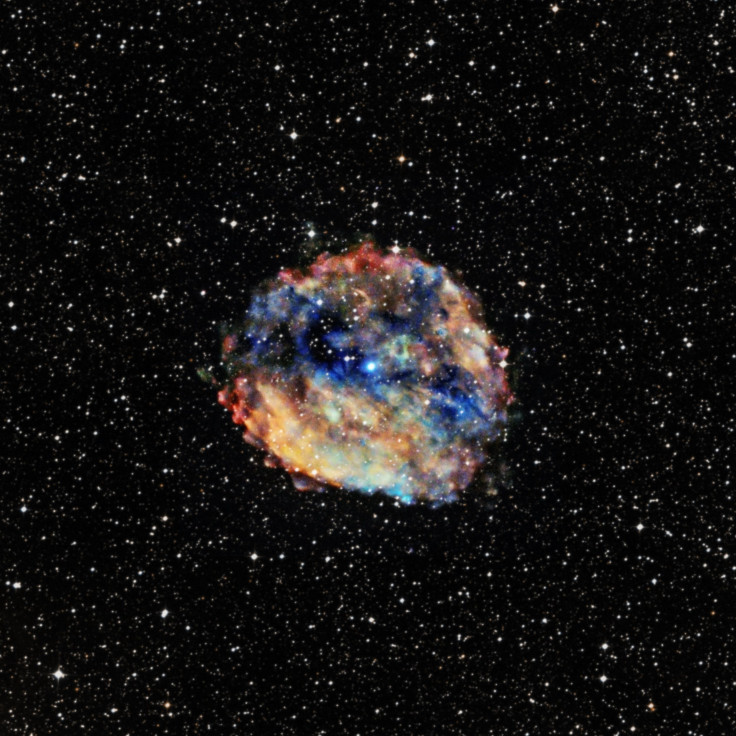

Over 2,000 pulsars — first discovered accidentally 50 years ago — are known by scientists today, and while we have learned some facts about these “beacons” in space after studying them for five decades, there is still a lot we don’t know about these collapsed stars. With its recently started NICER mission, NASA hopes to learn a lot more about pulsars, including what’s inside them.

The Neutron star Interior Composition Explorer, or NICER, was sent to the International Space Station aboard the last SpaceX Dragon capsule in June. From its ISS vantage point, the mission observed PSR B1919+21, the first pulsar observed in 1967. Now, it is observing other pulsars in the X-ray spectrum to see “how nature’s fundamental forces behave within the cores of these objects, an environment that doesn’t exist and can’t be reproduced anywhere else.”

Read: NASA Sends NICER Instrument To The Space Station To Study Neutron Stars

Keith Gendreau from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and the principal investigator for NICER, said in a statement Tuesday: “Many nuclear-physics models have been developed to explain how the make-up of neutron stars, based on available data and the constraints they provide."

"NICER’s sensitivity, X-ray energy resolution and time resolution will improve these by more precisely measuring their radii, to an order of magnitude improvement over the state of the art today,” he added.

Current theories about the make-up of neutron stars and pulsars involve particles we are already familiar with — neutrons, electrons, protons, and maybe even quarks. But how these particles will behave under the extreme conditions of pressure and density inside these bodies is something we don’t understand.

Pulsars are highly magnetic, fast-rotating neutron stars, and therefore have very short and regular rotational periods. This makes their radiation beam appear pulsating, with very regular intervals, much the same way you can see the sweeping light shining from a lighthouse. They start off as stars with masses between seven and 20 times that of the sun, and can spin up to hundreds of times per second. They are tiny in comparison to the stars that they used to be, only a few miles across, but are extremely dense, and their solid surfaces have temperatures of one million degrees.

Read: Pulsars Could Be Causing Excess Gamma-Ray Radiation At Milky Way’s Center

But astronomers have no concrete ideas about what lies at the cores of these stellar objects.

via GIPHY

Another use that NICER is being put to is for the demonstration of Station Explorer for X-ray Timing and Navigation Technology (SEXTANT), a two-in-one mission with NICER. The “demonstration will use NICER’s X-ray observations of pulsar signals to determine NICER's exact position in orbit,” which in turn will “pave the way for future space exploration by helping to develop a Global Positioning System-like capability for the galaxy,” according to the NASA statement.

Zaven Arzoumanian, also from Goddard, explained: “You can time the pulsations of pulsars distributed in many directions around a spacecraft to figure out where the vehicle is and navigate it anywhere. That’s exactly how the GPS system on Earth works, with precise clocks flown on satellites in orbit.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.