Special Report: In Saudi Arabia, a clamor for education

Saudi teenager Abdulrahman Saeed lives in one of the richest countries in the world, but his prospects are poor, he blames his education, and it's not a situation that looks like changing soon.

There is not enough in our curriculum, says Saeed, 16, who goes to an all-male state school in the Red Sea port of Jeddah. It is just theoretical teaching, and there is no practice or guidance to prepare us for the job market.

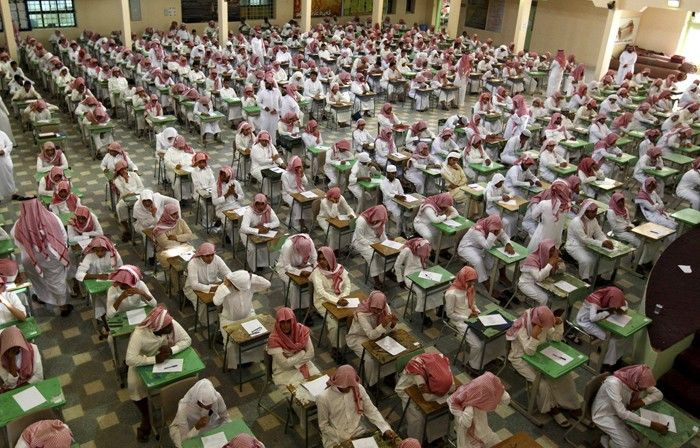

Saeed wants to study physics but worries that his state high school is failing him. He says the curriculum is outdated, and teachers simply repeat what is written in text books without adding anything of practical value or discussions. Even if the teachers did do more than the basics, Saeed's class, at 32 students, is too big for him to get adequate attention. While children in Europe and Asia often start learning a language at five or six, Saudi students start learning English at 12. Much time is spent studying religion and completing exercises heavy with moral instruction. One task for eighth grade students: Discuss the problem of staying up late, its causes, effects and cure.

In the face of rising unemployment, Saeed has taken parts of his education into his own hands. He learned how to use the internet on his own and sets himself research projects in his own time to try to make up for his school's shortcomings. The subjects available are not enough to carry us to the career or specialization that is needed for the job, he complains.

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia sits on more than a fifth of the globe's oil reserves and thanks to high oil prices it has almost tripled its foreign assets to more than $400 billion since 2005. The region's thinkers had a profound influence on the evolving western science of the Middle Ages. But from kindergarten to university, its state education system has barely entered the modern age. Focused on religious and Arabic studies, it has long struggled to produce the scientists, engineers, economists and lawyers that Saudi needs.

High school literature, history and even science text books regularly quote Koranic verses. Employers complain that universities churn out graduates who are barely computer-literate and struggle with English. So frustrated are some students, they have taken to the streets in protest.

Education in our country cannot be compared to education abroad, says Dina Faisal, mother of a 15-year old student in Jeddah. We have a lack of sciences, physics, and biology. That is what is needed to push the country forward. There has been some change but it is far from being complete.

Six years ago, alarmed by how many young Saudis were out of work, King Abdullah bin Abdul-Aziz launched an overhaul of state schools and universities. The effort is part of a raft of reforms designed to ease the influence of religious clerics, build a modern state and diversify the economy away from oil to create more jobs. The reforms are controversial, though, and nowhere more so than in education. Adding more science classes means scaling back on religion -- a direct challenge to the Wahhabi clerics who helped found the kingdom in 1932 and dominate vast parts of society.

The Saudi education system is particularly difficult to reform because it is traditionally one of the main areas where the clerics have influence, says Jane Kinninmont at the Economist Intelligence Unit. Asserting technocratic control over education may require a power struggle with the conservative clerics.

Many reform-minded Saudis were optimistic when Abdullah first announced the changes. Since then, though, the pace of reform has been slow. In the past few months the chance that Saudi's rulers will really take on the clerics has faded. King Abdullah, who is around 87, is recuperating in Morocco after two months of medical treatment in the United States. The slightly younger Crown Prince Sultan bin Abdul-Aziz has spent most of the past two years in Morocco and the United States because of an unspecified illness. Many Saudi observers believe Prince Nayef bin Abdul-Aziz, the veteran interior minister who has close ties to clerics and appears lukewarm on reform, has a good chance of taking over after his promotion to second deputy prime minister in 2009.

Reform? asks Simon Henderson, a Washington-based author of several studies on Saudi succession. It has been moribund... since Nayef became second deputy prime minister. Abdullah has also lost energy for it.

THE SPARK FOR CHANGE

Abdullah launched his $2.4 billion Tatweer initiative -- Tatweer is Arabic for development -- in 2005, promising to overhaul teaching methods, emphasize science and train 500,000 teachers. The king has repeatedly said that giving young people a better education is at the heart of his plan to build a modern state and fight religious extremism. Humanity has been the target of vicious attacks from extremists, who speak the language of hatred, fear dialogue, and pursue destruction, King Abdullah said in 2009 at the inauguration of the country's first mixed-gender university, a high-tech campus near Jeddah with an estimated budget of $10 billion. We cannot fight them unless we learn to coexist without conflict... Undoubtedly, scientific centers that embrace all peoples are the first line of defense against extremists.

Since then, the number of state and private universities catering to the 300,000 or so high school students who graduate every year has grown to 32 from eight before 2005, the ministry of higher education says. A large female-only university is under construction near Riyadh airport. Until the new universities take root, the government has given scholarships to 109,000 students to study in top universities mainly in the United States, Europe and the Middle East.

Schools too are changing. Within two years, all primary and high schools will get new mathematics and science textbooks that follow U.S. standards, the government says. Thousands of teachers are undergoing extra training. Primary schools will still focus largely on teaching Arabic and religion, but high schools will have more science and mathematics classes.

We don't say we have no problems but it is getting better. It's changing, says Nayef al-Roomi, deputy minister in charge of developing education, as he shows charts of curriculum changes in his office and tries to ignore the constant ring of his mobile and desk phones.

Education is not a factory. We will see at least three years to get results.

SLOW AND UNCERTAIN

So far, though, progress has been barely visible. A 2007 study by the respected Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) put Saudi students third-last in eighth grade mathematics. In the science category, the kingdom was fifth-last. Saudi Arabia also ranked 93rd of 129 in UNESCO's 2008 index assessing quality of education. Analysts say there has been no noticeable improvement in the kingdom's education standards in the past four years.

I think 10 years is a realistic option to see a real change if all plans are implemented, says a consultant who has worked for the education ministry and spoke on condition of anonymity because of the risks of challenging the official view.

A 2008 study by Booz & Company said progress had been made in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf Arab countries, agreeing that noticeable results can be obtained in a decade, even though realization of the full economic impact may require a generational period.

Even then, the changes will only go some way to overhauling the system. Take school textbooks. The government has started to cut comments that urged Saudis to kill infidel Christians and Jews. But the books still say Saudis should avoid non-Muslims. A reference in a new religious textbook seen by Reuters says that Prophet (Mohammed) has cursed Jews and Christians because they have built places of worship around their prophets' tombs.

In the past the textbooks used to refer to the infidels saying that they must be killed. Now it still refers to the infidels but says that we must not use violence in dealing with them, says Dina.

Changing that will require a mentality change, says the consultant. It's not just introducing new textbooks.

But clerics and conservatives dominate the education ministry, diplomats and education experts say. Conservative officials in mid-level positions sometimes delay or ignore directives from above. Textbooks and teaching methods appear not to change much.

We cannot really say that any comprehensive education reform program is underway, says the EIU's Kinninmont.

A QUESTION OF JOBS

The push to fix education is rooted in a fear that millions of young, unemployed Saudis -- 70 percent of the country's almost 19 million population is under the age of 30 -- is a recipe for radicalism. Fifteen of the 19 terrorists who attacked the United States on 9/11 were Saudis, while an al Qaeda bombing campaign inside the kingdom between 2003 and 2006 ended only after a massive government operation. Last year, 172 Saudis with al Qaeda links were arrested, proving Islamist groups are still actively recruiting in the kingdom.

The economy is ticking over nicely, and the U.S. ally has just unveiled its third consecutive record fiscal budget. The problem is, companies much prefer to hire expatriates instead of locals, in large part because of shoddy education. The number of expats working in Saudi Arabia has risen by 37 percent to 8.4 million in the past six years. Expats now fill nine out of 10 jobs in the private sector, according to John Sfakianakis, chief economist of Banque Saudi Fransi.

Labor Minister Adil Fakieh said on January 25 the government hopes to create five million jobs for Saudis by 2030 but economists think that's unlikely. Unemployment among Saudis has risen. Officially, the rate was 10 percent in 2010; the rate of female unemployment is probably triple that.

The state has introduced quotas on the percentage of local workers private firms must hire. But companies have become expert at circumventing the laws, by hiring lots of locals for low-level jobs, or breaking up firms into smaller entities just to have smaller quotas, says a banker in Riyadh.

In the past, many Saudis found work with the government. But the kingdom has one of the region's highest population growth rates so citizens no longer automatically get such jobs. In stark contrast to a generation ago, you can find Saudis working as taxi drivers, supermarket cashiers or private security guards, jobs which net as little as 1,500 riyals ($400) a month. I was surprised to see Saudis work in supermarkets. That would have been impossible 10 years ago, says a Western diplomat on his second posting to Saudi Arabia.

Nael Fayez, head of Injaz, a non-governmental organization that helps prepare students for the job market, believes education is the main problem. There is a rising gap between the requirements of the private sector and what state school produces, says. We need to fill the gap.

OPTION B

That gap is at least partially filled by a scheme to educate Saudi Arabia's brightest at foreign universities overseas. Officials who back the king hope the students will return with new ideas and a desire to shake things up. The problem: many prefer life abroad.

There are more things to do day-to-day: going to parks, cinemas, theater shows or restaurants with your friends or girlfriend, says Osama Zeid, a 23-year old Saudi studying in Boston. In Saudi, a teenager's spare time is filled watching television or going to a mall, where the religious police make sure no unrelated men and women meet at restaurants or cafes.

People are friendlier and everyone is socially accepted and more open-minded. In Saudi there is no entertainment. You need entertainment, says another Saudi attending the same university after graduating from high school in the U.S. city.

There is no data on how many Saudi students plan to stay overseas, but bankers in Riyadh say some of the best talent studying in the United States regularly ends up on Wall Street rather than heading home. Expectation-management is a big issue. Young people growing up with the internet won't be happy to sit at home even if the state guarantees a basic income, says a diplomat in Riyadh. They want to do something.

Saudi officials are also pinning their hopes on private schools and colleges at home which have sprung up in major cities in the past five years. A new technical college in a residential area of eastern Riyadh is one example. From the outside, the school looks like a typical state university -- high walls shielding white brick buildings clustered around a large mosque. Inside, the differences are radical. Germany's state aid agency GTZ, which gets paid for the project by the Saudi government, has installed laptops, Power Point presentation facilities, and electronic workstations. The aim of the 45 teachers who run the school is to turn out Saudi vocational teachers who can then transform how things work at more than 100 technical colleges around the country.

The students have already graduated from state technical high schools but feel they have entered a new world. It's totally different and better compared to the previous institute, the methods to try out things, the materials, says Mohammed al-Mansour, who came from Najran near the Yemeni border to study here.

Applications are piling up. Of some 2,000 requests the college has admitted 450 students so far but plans to expand to 2,000 by 2012.

It's just excellent, much better than had I expected, said 24-year old Ahmad Hamdashi from Riyadh, talking while his friends work on measuring power current on work stations at their desks.

The students' biggest surprise, perhaps, is to find that a teacher doesn't just have to read from a book. Let's do it again, says teacher Bernhard Homann, insisting everyone in the class tests the currents properly.

We want them to work out things on their own, says Raimund Sobetzko, vice dean at the school.

TOO MANY WRONG GRADUATES

Nayef al-Tamimi wishes he could have gone to such a college. Like thousands of other Saudis, al-Tamimi graduated from university as an Arabic language teacher but has struggled for years to get a job that pays a decent wage. At private schools, he makes about 2,000 riyals a month -- much less than the 8,000 he would get as a government teacher. At private schools I compete with foreigners. Egyptians, Jordanians, Palestinians. It's tough, he says.

This year he joined some 250 fellow graduates to organize a series of protests in front of the ministry of education in Riyadh, a bold move in a country that does not tolerate public dissent. Even though police quickly show up whenever the group gathers, Tamimi said the protests will continue until they all get the state jobs they so desperately seek. The government may eventually decide to hire the protesters just to end the demonstrations that have started to make global headlines.

But critics of the reforms, including political opponents, say the problems will remain until the ruling al Saud family allows more freedom and independent thinking -- the sort of progress that will depend on the future king.

Saudi Arabia has no elected parliament, but King Abdullah has forced Saudi society to open up ever so slightly. Saudi newspapers now debate reforms, women enjoy slightly more access to education and the job market. Would a more conservative king reverse those?

How can you reform education without democracy? asks Mohammed al-Qahtani, a veteran dissident based in Riyadh. I tell you that in five years there will be no improvement to education.

(Ulf Laessing reported from Riyadh and Asma Alsharif from Jeddah; Editing by Simon Robinson and Sara Ledwith)

© Copyright Thomson Reuters {{Year}}. All rights reserved.