Zika Virus Funding: States Feeling The Squeeze As Congress Holds Out On $1.8 Billion In Emergency Money

Dr. Edward Ehlinger is bracing himself for several tough decisions he may have to make in the coming months. Should the Minnesota Department of Health, of which he is commissioner, delay investing in new lab equipment to rapidly diagnose infectious diseases? Or, should it cut down on a stockpile of antibiotics that would prove crucial in the event of an outbreak?

Such sacrifices are distinct possibilities without an influx of federal funding, traceable directly to a battle in Washington, D.C., over the Zika virus.

As top officials at federal health agencies this week raised the alarm over the virus even higher, saying that the mystery of Zika poses dangers greater than they initially realized, federal funding to combat it could hardly be lower. The White House has scraped together $589 million, less than one-third of the $1.8 billion in emergency funding President Barack Obama requested in February that Congress has so far refused to approve. The funding squeeze has left state and local officials fearing they’ll soon be scrambling not just to protect people from Zika but also to sustain other vital public health programs as resources are diverted to the emerging disease.

“When Zika came along, it added another level of stress to an already underfunded system of emergency response,” Ehlinger said. In the two months that Congress has refused to approve emergency Zika funding, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention began scouring its budget for money to spend on mosquito control and other anti-Zika initiatives. It found $44.2 million for public health emergency preparedness, which it then cut from funding for local and state departments.

“We’re talking hundreds of thousands of dollars throughout our state,” Ehlinger said. “It’ll impact our overall emergency-preparedness efforts” for everything from Lyme disease to floods, he said.

Those same cuts amounted to nearly $3.6 million for Texas, where in Harris County, the Rhode Island-sized chunk of land surrounding Houston, the health department is ramping up its efforts to protect residents from Zika. This year, it is more than doubling the number of mosquito traps it puts out for the Aedes mosquitoes, which transmit the virus, from roughly 60 traps in 2015 to 135 now.

At $200 to $300 a pop, the traps themselves don’t constitute a major expense, said Dr. Umair Shah, executive director of the Harris County Public Health & Environmental Services. Rather, it’s the staff who pick them up and put them out, who test the mosquitoes caught in them for diseases, that consumes financial resources, Shah said.

Yet despite the fact that Zika is considered a national threat, local dollars fund 98 percent of mosquito control in Harris County, according to Shah. Over the next year, the department plans to spend anywhere from $2.5 million to $3 million fighting Zika, but that could change if the 12 confirmed cases so far countywide start to pick up. Already, the department is shifting more and more of its resources — and people power — to focus on the Zika virus.

“Over time, it starts to impact other activities,” Shah said, adding that people across the department, from communications to emergency preparedness to environmental health, were currently working on Zika.

“You end up taxing where those people are coming from,” he said. But Harris County, like everywhere else in the United States, has other health problems to deal with, such as chronic diseases like diabetes and high blood pressure, and infectious ones like HIV and tuberculosis.

“You sort of rob Peter to pay Paul,” said Josh Michaud, an associate director on the global health policy team at the non-profit Kaiser Family Foundation in Washington, D.C. “Relying on existing pots of money will likely damage public health in some way, shape, or form, if additional money is not provided,” he said. Of the $589 million that the White House cobbled together last week, $510 million of that came from funding for Ebola that was intended to help wipe out that virus for good and prevent future epidemics.

For many health officials and providers, the best solution remains for Congress to approve the White House’s requested $1.8 billion in extra funding, because ignoring Zika is not an option.

Part of what officials and the public alike find so alarming about the disease is the mystery engulfing it. The fact that it can be spread sexually is a recent discovery, and scientists have only just begun to understand the link between the virus and how it can damage the developing brains of fetuses. No vaccine for Zika exists, and even diagnostic tests remain unreliable.

For the majority of people, Zika virus is inconsequential; only one out of five people infected will suffer symptoms, usually mild ones, like a fever or a headache. For women who contract the virus during pregnancy, however, the potential implications are far graver. The virus has been linked to microcephaly and other potentially devastating birth defects in newborns, even as answers about what that means for women who are trying to become pregnant remain elusive.

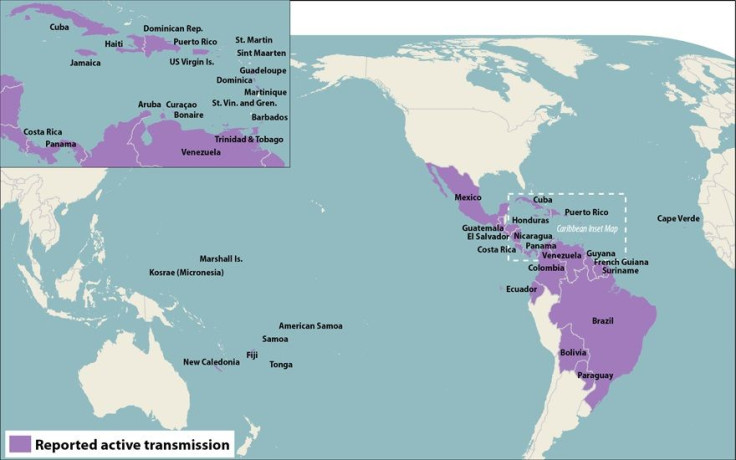

So far, more than three dozen countries and territories in Latin America, the Caribbean and the Pacific Islands have reported local transmission of Zika. Health officials fear that the U.S. will soon join that list. Already the continental U.S. has nearly 350 confirmed cases of Zika virus, all travel-related. Of those cases, 32 were pregnant women, and seven were transmitted sexually.

Every day, the staff at the 10 Legacy Community Health clinics throughout the Houston area field more and more questions from patients about the Zika virus. But they don’t know how to respond to many common queries, such as: “How long should I wait to get pregnant if my partner has been exposed to the virus?”

“We need more information,” said Katy Caldwell, the CEO of Legacy, which runs federally qualified health centers that often serve low-income patients. But without more funding at the federal level for crucial research, uncovering how the virus works and affects people is likely to come later rather than sooner, even as those questions remain urgent, and for many women, terrifying.

“The more definitive answers we can get, the better,” Caldwell said. “And the more rapidly we can get those answers, the better.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.