Donald Trump Executive Order: Syrian Man, Pregnant American Wife Almost Fled US Over Immigration Ban

A year and a half ago, Raji Alatassi, a Syrian-born businessman, and Mara Andersen, an American educator, were married in her home state of Colorado with their Muslim, Jewish and Christian relatives gathered around them, sharing traditional folk dances and sweets. Not long after, Alatassi took his first steps toward realizing two more of his dreams - becoming a father and becoming a citizen of the United States.

Those dreams were threatened Jan. 27 along with the those of at least tens of thousands of others whose visas were revoked when President Donald Trump signed an executive order barring immigration from seven Muslim-Majority nations in the Middle East and Africa. Alatassi's native Syria was one of them. While it was not immediately apparent whether the order affected people already within the U.S., the idea of having to fight to stay in the country was not a situation the couple had imagined as they prepared to start a family. Andersen was due with their first child in a matter of weeks and she and Alatassi feared they would be forced to leave home over Alatassi's immigration status.

"A year and change ago was a time of so much hope for us," said Andersen, the executive director of an organization dedicated to internationalizing universities in Colorado. "We had family from all over the world dancing circles around us, saying this is who we are. After this weekend, we had to look at ourselves and say, 'Is this who we are?'"

Alatassi and Andersen's story is just one among countless other immigrants who have expressed their fear of how the Trump administration's policies will affect their path to citizenship in the U.S. as well as the political climate they will endure for at least the next four years. Trump's executive order has since been suspended by a federal judge, however, the White House is expected to argue on behalf of the travel ban until it reaches the Supreme Court.

Alatassi was born in Damascus and grew up in Aleppo before visiting the U.S. for the first time when he was 12. He vowed to return. He left Syria for Canada at age 16 and later got his business degree from Valparaiso University in Indiana. He received his Canadian passport, and decided to work abroad in the oil and gas industry across the Middle East and North Africa.

While working in Abu Dhabi, he met Andersen, who then was an assistant public affairs officer at the U.S. Embassy in the United Arab Emirates. The two hit it off, but work would keep them apart - geographically at least - for the next six years until they reunited in Houston, where they reside to this day. Alatassi works as a business development manager at Honeywell Automation under an H-1B visa for skilled workers. The document expires in May and, without work, having to leave the country in the next few months was a very real possibility.

"I'm gonna be on the run again? I have to find somewhere else to live? That's kinda crap," Alatassi said, recalling that his emotions ranged from anger to fear to shock when he first heard of the executive orders.

Alatassi said he had already prepared for the worst upon hearing the news of Trump's electoral victory and had even heard whispers of a new, formidable law affecting immigrants from the Middle East prior to the executive order being passed. All the more reason that Alatassi was anxious to get his green card application recognized. It was one of over 300,000 family-based status adjustment applications received that year.

He attended his USCIS interview in November and submitted extra medical documents in December. The process was in its final steps, awaiting a decision by the USCIS officer, when Trump announced his executive order. Both Alatassi, 36, and Andersen, 38, scrambled to find answers, but found information was scarce even among immigration lawyers and activists.

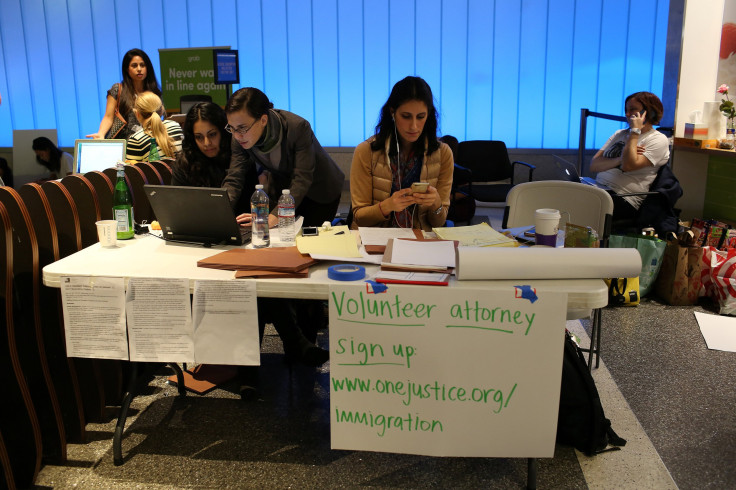

Firms specializing in immigration law flocked to the nation's airports to support immigrants whose travel visas had been invalidated overnight. Mass panic ensued as arriving passengers were questioned, detained and, in some cases, forced to return. Meanwhile, visa holders and permanent residents already in the U.S. anxiously waited to hear how this new, sudden law might apply to them.

"They were not supposed to hold or freeze these cases," Joe Perez, an attorney at Houston's Foster immigration law firm who Alatassi consulted explained. "All of this was done in a haphazard way. The president just sort of did this unilaterally without consulting any other government agencies."

When Trump signed the executive order temporarily banning citizens of Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen, he reportedly neglected to adequately consult other federal authorities. Not even USCIS was entirely informed of the scope of the new law. As a result, Alatassi's green card application was frozen. He and his wife were taken aback by the news.

The following week consisted of reaching out for community support, consulting immigration lawyers and formulating backup plans to move as far away as East Asia, where Alatassi maintained business contacts from her State Department work in Hong Kong. Neighbors offered to shelter the couple in the worst case scenario and countless letters were sent to local politicians and organizations. Finally, USCIS informed them last week that Alatassi's green card was being adjudicated after all.

While the couple said the outpouring of support from family, friends and even strangers uplifted them, the traumatic experience has given them cause for concern over the direction of the U.S. Raji likened his feelings to the atmosphere of the country after 9/11 when he first began to question whether the country he wanted so bad to be a part of actually wanted him.

Following the 2001 attacks, federal authorities documented a record 481 hate crimes. The next highest spike was 2015, with 260 recorded hate crimes, raising fears among the immigrant community that the trend would only worsen under a Trump presidency.

Andersen breaks down when she imagines her husband's journey to the U.S. and at the thought of him feeling rejected by what she calls an "arbitrary" piece of legislation that targets people for where they came from and not who they are. She refers to recent political events as a "wheel of misfortune" that one week points to immigrants such as her husband, but next week could turn on other minority communities of different backgrounds or sexual orientations. She said the U.S. was a "resilient country," but that "it felt like dark times."

Alatassi said he fell in love with the U.S. because it opened its arms to people of all backgrounds and offered a unique opportunity for freedom. It housed a number of his relatives who themselves left Syria in the 1980s to emigrate, an impossibility under Trump's executive order. Now, Alatassi wonders whether Trump's pledges to "make America great again" are all that different from the rhetoric he remembers hearing from certain Arab World governments growing up, which he described as always looking backward, recalling past glories and allowing current problems to fester.

"I think one of the most alarming things I’ve seen in this country is that they’re looking to the past," Alatassi said. "When Trump was elected a lot of people said this was just campaign rhetoric. I grew up in Syria. I know the difference."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.