Fat-Shaming And Body-Shaming, A History: Author Talks Thigh Gaps, 'Dad Bods' And Why We Hate Fat

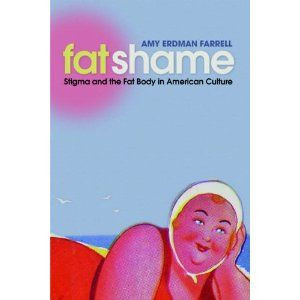

When body-shaming cartoons that a Lilly Pulitzer employee posted near her cubicle went viral on Wednesday, the Internet exploded with self-righteous indignation. But as Dickinson College professor Amy Farrell's book "Fat Shame: Stigma and the Fat Body" (NYU Press, 2011) makes clear, fat- and body-shaming can be traced back to mid-19th century England, when the first modern dieting book was published.

While fat became public enemy number one, it was women's bodies that largely became the site of cultural, racial and class anxieties of which fat phobia is a sign. These anxieties and their contradictions are alive today, in a culture that, on one hand, tells women that "Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels" and celebrates "thigh gaps" in photos. On the other hand, it tells women that it's the age of the butt or that they need large breasts -- not often found (naturally) on ultra-thin bodies.

Men, meanwhile, get to have "dad bods."

"Having a superior body is how we demonstrate we’re superior," Farrell told International Business Times. "Culturally, there becomes a whole group of people who aren’t superior: the fat people, which links up to race, class and gender. We don’t call it that, though; we say we want to be healthier."

The very same behaviors that would identify a thin person as having an eating disorder, Farrell noted -- restricting food, obsessive attention to diet and exercise, obsessive attention to body weight -- is what gets "prescribed" for a fat person. (She writes more about this "Fat Chance: The Line Between Health and Shame Is Becoming Increasingly Thin.")

International Business Times: How did you start writing about fat-shaming?

Amy Farrell: I work on the history of women and feminism, and had just completed a history of Ms. magazine. I was looking for another subject, and began researching the history of dieting. It got pretty boring. There have been milk, all-protein, grapefruit diets going back to the 19th century. What was interesting was how all the diets talked about fat.

I thought the dieting industry started in 1920s. It looks like that because there were so many ads for diets then. But it started among middle-class white people -- with the growth of the middle class. Fat was the evil antagonist, the sign of an uncivilized and "primitive" body. It was linked with "scientific" racism that [attempted] to prove that African people and indigenous people were inferior. One sign? Fat: the atavistic, primitive trait. And it continues today. I’m not surprised that someone would have those pictures up at Lilly Pulitzer.

IBTimes: So if the fear of fatness is related to racism, can we assume that because Jennifer Lopez and Beyonce’s bodies are idealized, particularly their backsides, and women are even getting butt implants to emulate them, that there’s no longer a connection between certain races and ethnicities with fat?

Farrell: It [privileging of bigger backsides] is connected [to that racist discourse]: a sign of wild sexuality. I would argue it’s same thing. Because the butt still has to be shaped in a particular way. If we go back in time, the bustle would have been the same thing: over your skin, instead of under.

It's like tanned skin. It’s ironic that it has been historically a sign of wealth and beauty, because dark skin is often seen as inferior. It's a desirable thing if kept within its bounds. It's like the difference between a "redneck" versus a bronzed beauty, whose tanned skin would be a sign of her elite status, a sign of leisure.

IBTimes: Did you see shifts in body types over the 20th century? Were there reasons?

Farrell: I found less a shift than an increasing, strengthening feeling about fat. It’s rather that one strand took hold more strongly. In the middle of the 19th century, fat was suspect. It was still a sign that you’re healthy and fertile, well-to-do. But for men, the “fat cat” had a lot of power. Just think of images of a man with a big belly and pocket watch, like the horrible banker Potter in "It's A Wonderful Life."

What became increasingly the case, for middle-class people aspiring to a higher standard of living, was that the thin body was important. Thinness proved one was disciplined, civilized. That became increasingly true. A few presidents were fat, but it'd be harder to be a fat president now. Grover Cleveland was teased for being fat.

IBTimes: What were some signs of the shift to fat-shaming and fat-phobia in the mid 19th century?

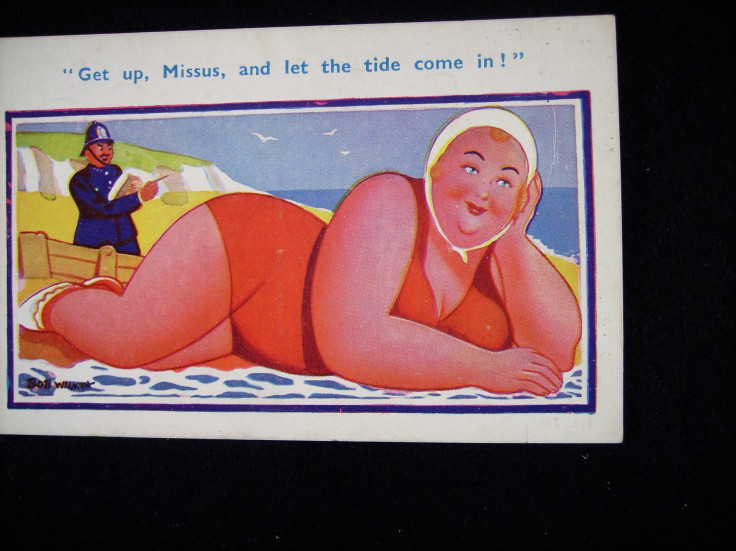

Farrell: The first diet book was published in England, in mid 19th-century. And in the late 19th century and into the 20th century, you started seeing "fat women" postcards. Dieting materials from that period were addressed to white men, saying to them, "We know that in less civilized, primitive cultures, fat women are considered beautiful. We are not Hottentots or Moors. For us, a fat body doesn’t hold an allure." What's interesting was that it was teaching white men to not like fat women. It's like the attractiveness of fat women had to go underground.

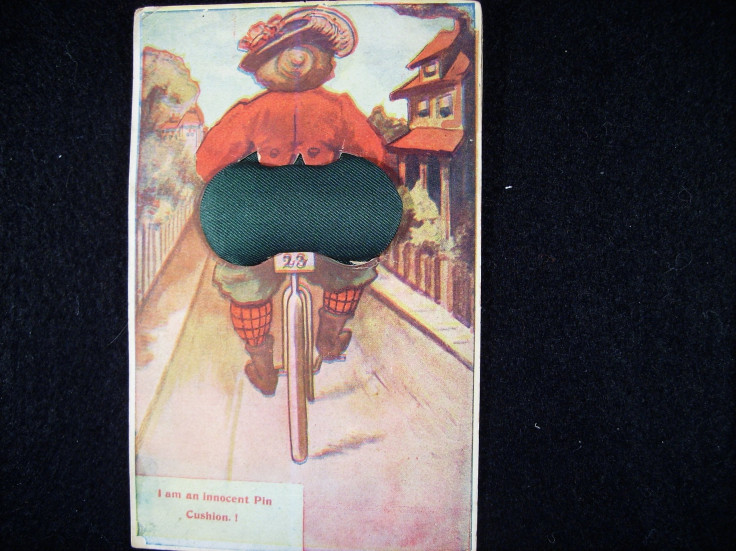

IBTimes: Who was buying these postcards?

Farrell: They were postcards people would pick up at tourist sites. Instead of texting, they’d send postcards they bought at the corner pharmacy. The postcards were like memes today. The postcards would show a fat butt, sometimes as a pincushion. Joking about the fat butt goes way back, back to the "science" surrounding African people and the Venus Hottentot. [Saartjie Baartman was the so-called Hottentot Venus, a woman whose large buttocks caused her to be exhibited as a "sexual freak-show attraction" in 19th century Europe.] After she died, Doctor Georges Cuvier dissected her body to see that she was human, and wasn't a missing link between beast and people. And it was because of her fatness. Those buttocks were enticing and interesting, and read as a sign of primitiveness.

IBTimes: And before mid-19th century? Was fat OK?

Farrell: Having a little plumpness was a sign of fertility, wealth. Diseases like tuberculosis made you thin. Thinness has been about not crossing a line. I didn’t see evidence of a time when fatness was celebrated. I wanted to find it, but I haven't seen it.

IBTimes: Did fat-shaming apply equally to men and women?

Farrell: The father of the diet movement, William Banting, was upset about his own body being fat. It’s not that men have been outside the diet industry or its pressures, but the most public ridicule and emphasis has fallen and continues to fall on women’s bodies. There’s more of a window for men’s bodies. They can become bigger before crossing into unacceptability. There's no cultural place for her to take up a lot of place, but taking up space is considered a right for men.

I would never want to say men are immune, though. Chris Christie had weight-loss surgery, and he doesn’t seem the type to worry about taking up space. But there is cultural pressure on the national stage to get the body “under control.” But when it comes to the weight-loss industry -- surgery, diets, diet products -- it's mostly women. And they're getting younger and younger. It's like the person’s fat body doesn’t have a right to exist.

IBTimes: Just recently, we were all told that "dad bods," bodies of men that seem to work out a little bit but still have a gut -- are in. We don't hear much about "mom bods."

Farrell: It’s connected to the “allowance” men get to take up more space, for example, "manspreading." Fatness in men, up to a certain level, allows them to be "Everyman," human, approachable. There's more of an allowance for men than there is for women.

IBTimes: Is there a cultural driver for moments when thin is more in? Like in the 1920s with the flapper's body, or Twiggy in the 1960s -- or now, compared to the supermodels of the 1980s, when size 6 was considered OK?

Farrell: Even size 6 is very little. It seems that the more rights women got, there was a cultural pressure for size to go down. Thinness as sign of civilized body. People often talk about "healthiness," but it's really a cultural anxiety about the fat body. People know they’re discriminated against, so they'll do a lot: Diet pills, surgery. There are complications from what happens to their bodies after surgery. They can’t absorb nutrients and even become malnourished.

I also think money is factor. We have a $67 billion diet industry. That works because people hate their bodies.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.