NASA’s Spitzer Telescope Finds Possible Exoplanet Which Is Smaller Than Earth, Extremely Hot And Incredibly Close

Scientists have found evidence for a new planet that could be the nearest world to our solar system. Yes, NASA astronomers using the Spitzer Space Telescope have detected what they believe is a planet two-thirds the size of the Earth.

The exoplanet candidate, dubbed UCF-1.01, is just 33 light-years away from our home planet and is the first to be identified by the Spitzer telescope. The discovery points to a possible role for Spitzer in helping discover potentially habitable, terrestrial-sized worlds.

We have found strong evidence for a very small, very hot and very near planet with the help of the Spitzer Space Telescope, said Kevin Stevenson from the University of Central Florida in Orlando. Stevenson is the lead author of the paper, which has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal. Identifying nearby small planets such as UCF-1.01 may one day lead to their characterization using future instruments.

According to NASA, exoplanets circle stars beyond our sun. So far, only a handful of smaller-than-Earth exoplanets have been found.

UCF-1.01 was found unexpectedly by scientists while studying the Neptune-sized exoplanet GJ 436b, already known to exist around the red-dwarf star GJ 436. In the Spitzer data, the astronomers noticed slight dips in the amount of infrared light streaming from the star, separate from the dips caused by GJ 436b. A review of Spitzer archival data showed the dips were periodic, suggesting a second planet might be blocking out a small fraction of the star's light.

This technique, used by a number of observatories including NASA's Kepler space telescope, relies on transits to detect exoplanets. The duration of a transit and the small decrease in the amount of light registered reveals basic properties of an exoplanet, such as its size and distance from its star.

In UCF-1.01's case, the possible exoplanet's diameter would be approximately 5,200 miles (8,400 kilometers), or two-thirds that of the Earth. UCF-1.01 would revolve quite tightly around GJ 436, at about seven times the distance of the Earth from the Moon, with its year lasting only 1.4 Earth days.

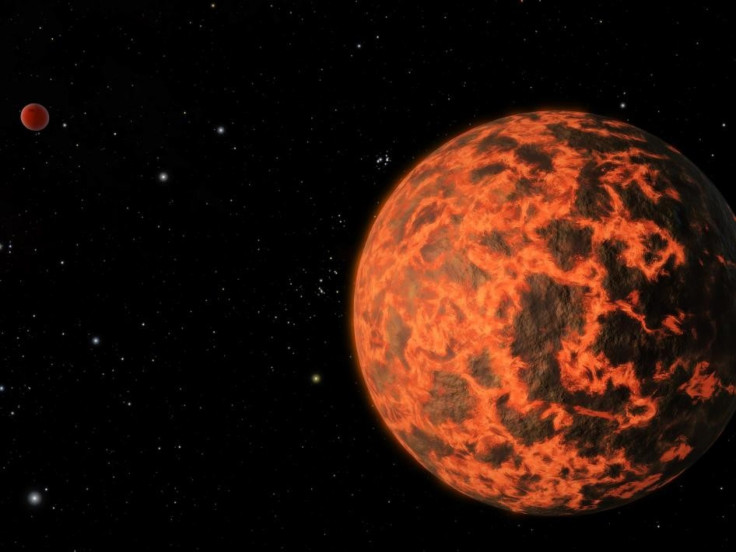

Based on UCF-1.01's proximity to its star, far closer than the Mercury is to the Sun, the exoplanet's surface temperature is expected to be more than 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit (almost 600 degrees Celsius). If the planet ever had an atmosphere, it almost surely had been evaporated, making it a cratered, mostly geologically dead world like Mercury, according to the scientists.

Joseph Harrington of the University of Central Florida and principal investigator of the research, who also co-authored the paper, suggested another possibility. He said that the extreme heat of orbiting so close to GJ 436 has melted the exoplanet's surface.

The planet could even be covered in magma, Harrington said.

Apart from UCF-1.01, scientists found hints of another planet, dubbed UCF-1.02, orbiting GJ 436. However, even the most sensitive instruments are unable to measure exoplanet masses as small as UCF-1.01 and UCF-1.02 and given that, knowing the mass is required for confirming a discovery, both the bodies are being called as exoplanet candidates for the time-being.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.