New Luxor Governor’s Link To 1997 Temple Massacre Sparks Protests, Tourism Concerns In Egypt

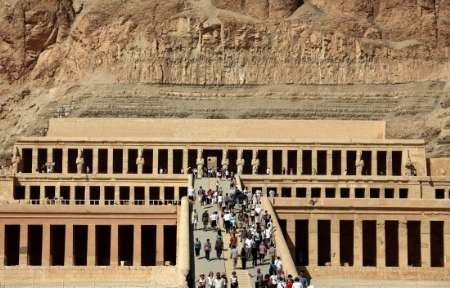

The entire world was shocked in 1997 when a hardline Islamist group slaughtered 58 tourists at the 3,400-year-old Hatshepsut Temple in Luxor’s Valley of the Queens. Sixteen years later, Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi stunned the world again when he appointed a member of that very same group, Adel Mohamed al-Khayat, as the new governor of Luxor.

Al-Khayat is a founding member of Gamaa Islamiya, the terrorist group responsible for some 1,200 deaths during a campaign of violence it, along with another militant organization, Islamic Jihad, perpetuated during the 1990s, when Hosni Mubarak ruled Egypt. Al-Khayat was also detained (but not charged) in the assassination of President Anwar el-Sadat in 1981.

Morsi’s decision to make the man governor of Luxor sent shockwaves through Egyptian tourism, culminating in the resignation of Tourism Minister Hisham Zaazou. Prime Minister Hisham Kandil has not accepted Zaazou’s resignation (and he remains at his post), but the gesture underscored a sharp divide in government and what many critics have called “the last nail in the coffin” to Egypt’s beleaguered tourism sector.

“When I heard about the appointment, I remembered the whole scene,” the head of Luxor’s Tourism Chamber, Tharwat Agamy, told the Associated Press. “With my own arms, I carried the blooded bodies of the women, children and men. … It is unimaginable that those who plotted, participated or played any role in the massacre of Luxor become the rulers, even if they renounced and repented it.”

Al-Khayat reiterated to Reuters Tuesday that he had no role in Gamaa Islamiya’s militant past, including the 1997 massacre, which was designed to cut off all tourist revenue to Mubarak's regime. He said his role in the group was restricted to university seminars, and added that all tourists visiting the region would be safe under his control.

“Luxor is open to all tourists from all over the world," he said. "They are my main concern and are looked after by the state, which is responsible for their security and their well-being."

Hundreds of protesters who gathered outside of the governor’s office for a second day Tuesday weren’t convinced. They carried signs that read, “The government has replaced an ambassador with a terrorist,” and announced plans to seal off the site to prevent al-Khayat from taking office.

Luxor is one of the crowning jewels of Egypt’s tourism industry and is home to ancient landmarks like Karnak and Thebes and important tombs, including that of King Tutankhamun. But the region celebrates the works of pre-Islamic Ancient Egypt, and many hardline groups deem the statues pagan idols that need to be demolished.

The Egyptian Coalition to Support Tourism fears that the site’s world heritage is now in danger. Ihab Moussa, the organization’s head, told Ahram Online that he would lodge an official complaint with Unesco if Morsi did not reverse his decision in 72 hours.

“We will inform Unesco that our antiquities in Luxor, which are considered world heritage sites, are in danger because the man in charge of them belongs to a terrorist group that committed the Luxor massacre,” he said. Meanwhile, Unesco released results last week of its mission to Timbuktu in Mali, where radical Islamists recently destroyed irreplaceable artifacts.

“The destruction caused to Timbuktu’s heritage is even more alarming than we thought,” said mission leader Lazare Eloundou Assomo of Unesco’s World Heritage Center. “We discovered that 14 of Timbuktu’s mausoleums, including those that are part of the Unesco World Heritage sites, were totally destroyed, along with two others at the Djingareyber Mosque. We estimate that 4,203 manuscripts from the Ahmed Baba research center were lost, and that another 300,000 were exfiltrated -- mainly to Bamako -- and are in urgent need of conservation.”

Beyond the fears of similar destruction in Egypt, there are concerns that many things vital to attracting Western tourists could change. Al-Khayat’s Construction and Development party, the political arm of Gamaa Islamiya, has already called for a stricter implementation of Sharia law, which could outlaw everything from bikinis and gender mixing on the beach to alcohol at the restaurants. None of these threats have become a reality, but looming uncertainty in Egypt ever since the overthrow of Mubarak in 2011 has taken its toll on the vital industry.

Tourism is the largest economic driver in Luxor, the main city in a province of about 1 million people. While Egypt’s tourism numbers bounced back from 9.8 million in 2011 to just over 11.5 million last year, visitors concentrated in the nation’s beachside resorts, rather than in Luxor’s Nile Valley.

Hotel occupancy dipped as low as 17 percent this spring, according to local reports, and visitor spending nationwide is down to an average of just $70.30 per night, compared to $85 in 2010 before the revolution. Arrivals for April showed a slight increase over the previous year at 5.2 percent, though the latest row (and the negative publicity it has created) is sure to bring numbers tumbling down once again.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.