The Other Libyan Terrorism Case: After Years Of Waiting, Victims Still Seek Justice

On Sept. 26, 1986, a married couple with four children encountered terrible tragedy on the tarmac of Jinnah International Airport in Karachi, Pakistan.

Seetharamiah Krishnaswamy and his wife were on their way to the United States for their daughter’s wedding. They had flown to Karachi from Mumbai, India, and from there they planned to catch a flight via Germany to New York City.

But after landing at Jinnah, the airplane was hijacked by militants from the Abu Nidal Organization, an international terrorism outfit. The assailants tried and failed to reroute the plane to Israel, killing 20 innocent people in the process. “I lost my father and my mother was wounded,” said the late Seetharamiah Krishnaswamy’s son, Prabhat Krishnaswamy, who now resides in Ohio.

The lead hijacker was sentenced to life in prison in 2004, at which time Krishnaswamy learned from press reports that the Moammar Gadhafi regime had supported Abu Nidal and was implicated in the atrocity. “That’s when we decided to hold Libya responsible,” he said, by entering into a lawsuit against the country.

But no justice has yet been delivered for Krishnaswamy. For him and other victims of Libyan terrorism, the struggle for a resolution has stretched on for more than 15 years.

Today, at long last, a resolution seems to be close at hand – but only for those who were American citizens at the time of their injury or loss. And even they are still holding their breath; given the years of runaround endured by the victims of Libyan terrorism, there is still reason to suspect their compensation may yet be delayed by some unforeseen bureaucratic holdup.

As for Prabhat and dozens like him who became U.S. citizens only after the tragedies occurred, the battle is far from over.

Death and Delay

During his 42-year reign, Gadhafi supported militant groups from various countries. The situation was at its worst during the 1980s, when a series of attacks killed hundreds of people. Pan Am 73, the 1986 flight from Pakistan, was only one of many tragic incidents.

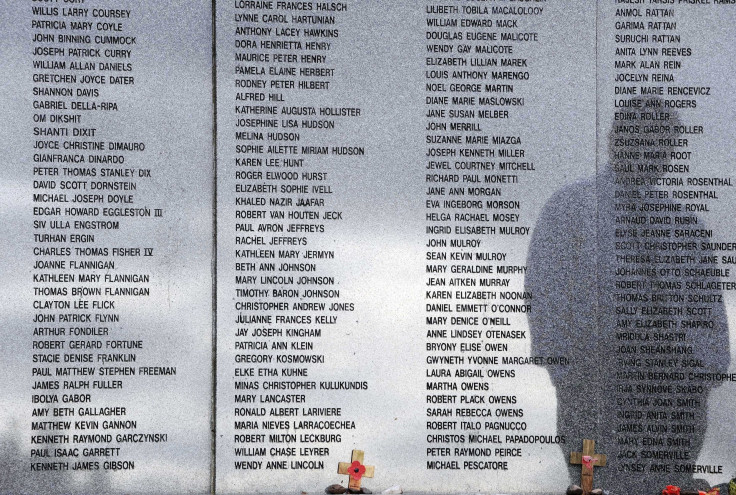

On April 5, 1986, a bomb exploded at La Belle, a West Berlin discotheque frequented by American troops, killing three and injuring more than 200. On Dec. 21, 1988, Pan Am Flight 103 from London to New York City exploded over Lockerbie, Scotland, killing all 259 people on board and 11 people on the ground. On Sept. 19, 1989, Pan Am Flight 772 exploded over the Sahara Desert, killing all 170 people on board.

As a result of these and other incidents, military actions were taken, severe sanctions were imposed and Libya was placed on the American list of state sponsors of terrorism in 1979. But in 2006, the administration of U.S. President George W. Bush dropped that designation. Gadhafi had apparently distanced himself from terrorist actors, renounced efforts to acquire weapons of mass destruction and engaged in secret negotiations with American officials. In 2008, the U.S. and Libya resumed diplomatic ties and Gadhafi agreed to pay $1.5 billion as part of the Libyan Claims Resolution Act, or LCRA, to compensate American families affected by attacks. In exchange, Libya’s legal liabilities to American citizens were effectively nullified.

Shortly after Libya delivered the funds, American victims of the most high-profile incidents -- including Lockerbie and the discotheque explosion -- received their compensation, leaving an estimated $400 million still available for disbursal. The remaining victims and their family members had to argue their claims in order to receive compensation; they were referred to the Foreign Claims Settlement Commission, a division of the Justice Department.

Some 252 claims have been filed with the FCSC since 2008, and awards were eventually granted to 141; the rest were denied. Total awards amounted to $370.8 million, but that money has yet to be delivered. Those 141 victims and families have been lost in a bureaucratic maze of false leads and dead ends. Egregious delays left many wondering where their money had gone, and whether it would ever be disbursed.

The reason for these hang-ups remains hazy, and neither the FCSC nor the Treasury will comment on the details. It could result from a range of factors including outsized claims from insurance companies, ongoing appeals, or disputes about reimbursing claimants like Krishnaswamy who were not American citizens at the time of the terrorist attacks.

Once those decisions were finalized, the Justice Department bowed out. According to an FCSC spokesperson, the organization “does not play any role in the payment process… it is the Treasury Department’s responsibility to make payments on certified awards. Beyond certifying awards to Treasury and State, the FCSC does not officially interact with those agencies regarding dispersal.”

Ever since their cases were decided, the 141 claimants have been struggling to keep track of their award statuses with the Treasury and the State Department. Meanwhile, Krishnaswamy and dozens more former foreign nationals were left out in the cold. “Our civil action was dismissed as a result of the LRCA in 2008, and only Americans as of the date of the attack were eligible to file claims before the FCSC,” he said.

Battling Bureaucracy

The Treasury tried to calm frayed nerves in 2011 by offering initial payments of $1,000 plus 20 percent of awarded amounts to those who were awaiting funds. But some found that decision alarming; it seemed to suggest that the funds procured from Libya in 2008 would not be enough to make good on the FCSC’s promises, fueling speculation about misappropriation.

The State Department has been reticent to address this subject for years -- even with prodding from the U.S. Congress. In two letters to then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in September 2011, politicians from both sides of the aisle in the Senate and the House of Representatives called for a resolution to the Libyan funds conundrum.

Assuming that the amount left over from Gadhafi’s initial $1.5 billion transfer had been depleted, these officials suggested another, more controversial source of funds -- the approximately $30 billion of assets that were seized from Gadhafi during Libya’s 2011 revolution.

“The families of those who were victimized by Qaddafi-sponsored terrorism deserve every cent that they are owed, and the United States government is in a unique position to do just that from Libyan assets currently frozen in the U.S.,” said Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., in the Senate letter.

This idea threw yet another wrench into the proceedings. The assets seized by the United States in 2011 were not intended for the compensation of Americans, and Libya’s transitional government asserts its own right to the assets to help fund the reconstruction of a battered country. The fate of those monies is apparently unresolved; the Treasury referred questions about their status to the State Department, which could not comment and suggested querying the Treasury.

Good news finally came on June 6, when a post on the website of the Treasury’s Financial Management Service suggested that the assets need not be involved after all.

“Treasury calculates that there are sufficient funds available under the Libya program to support making final payments to awardees in amounts that, when added to previous payments, will total 100 percent of their award amounts,” it said.

Endings and Beginnings

A spokesperson confirmed that the Treasury is now sending out letters to the 141 claimants still awaiting their compensation as awarded by the FCSC, kicking off the process by which victims and their loved ones can finally acquire the money that has been promised them. The letters began arriving at claimants’ homes in mid-June.

As of this writing, at least one American claimant has not yet received notice that funds are forthcoming; it would seem that further delays for some wouldn’t be entirely out of the question, especially given the history of bureaucracy surrounding the Libyan fund.

And then there are those like Krishnaswamy, whose battle for recognition and compensation is ongoing. There should still be some money left in the LCRA account once all the claimants are paid, though the Treasury cannot reveal how much. Krishnaswamy is hopeful that some of that could be used to compensate the dozens of people in his situation.

“We are aware that there will be funds left over after all awards from the FCSC are paid in full,” he said. “And we are strongly urging the State Department to address our claims as well, given that we are American victims of a Libyan sponsored terrorist attack on an American flagship carrier, who are also seeking justice and have no other government to represent us!”

Today, the international focus on Libya has much more to do with recent terrorism – the 2012 attack that killed four Americans including U.S. Ambassador Chris Stevens in Benghazi – than with the incidents that took place under Gadhafi. The dictator has been killed by the people he used to rule, and Libya is dealing with its own security issues in the wake of a violent revolution.

But what happened all those years ago is still not over – far from it. Some American victims are only just now getting the compensation they were promised. Some, like Krishnaswamy, still have nothing.

And even if justice is finally delivered, the tragedy can never be undone. The murderous actions of Gadhafi and his terrorist beneficiaries still manifest themselves today as deeply felt absences – losses that no amount of compensation could ever begin to address.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.