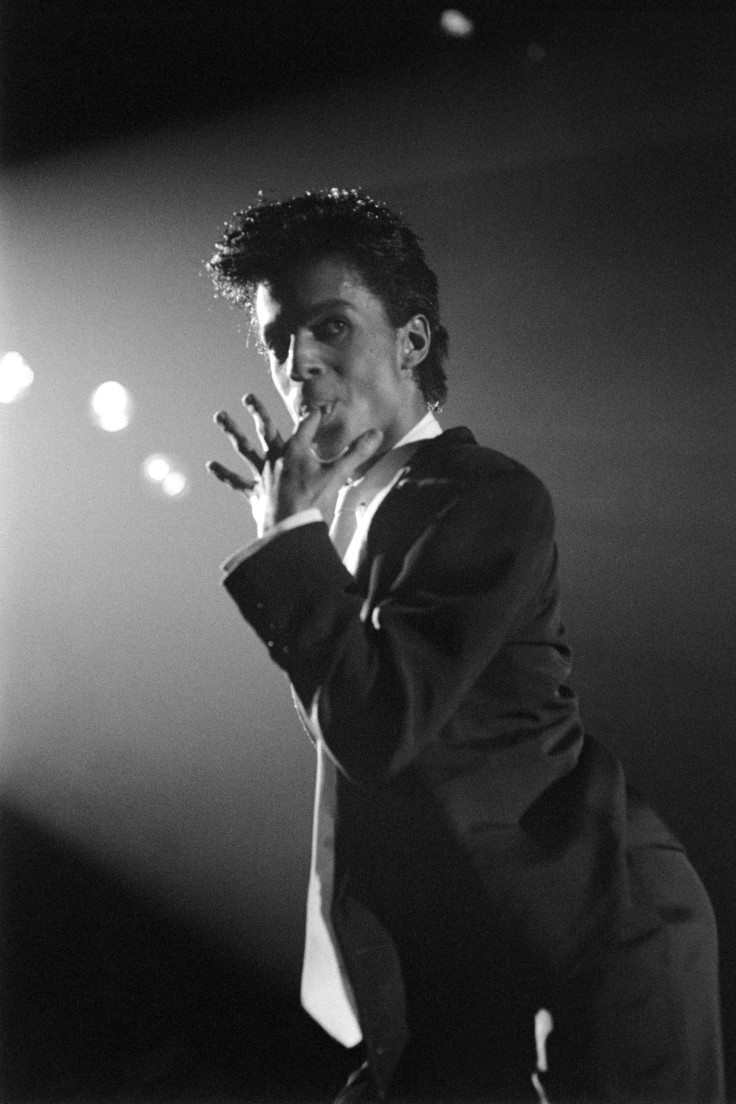

Prince, A Gender-Fluid Symbol, Pushed Boundaries Of Sexuality And Funk

Thelonious Monk once said true creativity is making something weird seem simple and self-evident. That is what Prince, the musician, songwriter, producer and pop culture auteur who died Thursday at 57, did for 40 years.

Born June 7, 1958, Prince Rogers Nelson was the son of jazz musicians who played in a group together in and around Minneapolis. He began teaching himself to play the piano at the age of seven, and by the time he was 14 he could also play the guitar and drums and was leading a band called Grand Central.

Six years later, in 1978, he had a record deal with Warner Bros., and the earliest versions of what would come to be known as the "Minneapolis sound," a lean hybrid of funk, rhythm and blues, pop, rock 'n' roll and disco that launched the careers of numerous acclaimed musicians, including the platinum-selling, Grammy-winning producers Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, Morris Day and the Time and Sheila E, came out of Prince in a torrent.

He released seven solo albums in seven years, each landing multiple songs on the Billboard pop and R&B charts, and also produced career-launching albums for the Time, a band cobbled together mostly with people that he knew from high school, and Sheila E.

Those albums, all but two of which ultimately went platinum, including such now- classics as “Purple Rain,” “Little Red Corvette,” “When Doves Cry,” “I Would Die 4 U,” “Let’s Go Crazy,” “Nasty Girl,” “When You Were Mine” and “Controversy.”

Today, pop music that borrows and synthesizes a number of genres has become commonplace. But in the late ’70s, with Disco Demolition Night just around the corner and musical genre conventions still segregating most music listeners from one another, hearing those sounds gyrate together was revolutionary.

And beyond the bold, visionary synthesis of genres, the music on those albums was also defined by a toe-curling sexuality. There were songs about incest, sleeping with a bride on her way to the altar, oral sex and threesomes that radio DJs couldn’t touch, but that burned themselves into fans’ ears anyway. On the road, Prince performed wearing bikini bottoms and a trench coat, dancing and performing with a volcanic yet androgynous energy — gay and straight, male and female, a romantic and a lothario. “Mick Jagger should fold up his penis and go home,” the rock critic Robert Christgau wrote of Prince’s second album, “Dirty Mind.”

Not everyone found his identity-testing persona appealing. “With his mass of carefully tended, black curly locks and his large, dark doe eyes, he looks, in repose, like a poster of Liza Minnelli on which someone has lightly smudged a mustache,” wrote the veteran New York Times critic Vincent Canby in 1984, reviewing “Purple Rain.” “When astride his large motorcycle, as he is from time to time, the image suggests one of Jim Henson's special effects from a Muppets movie: Kermit the Frog on a Harley-Davidson. In the depths of depression, pacing back and forth in his dressing room, he expresses all the pent-up rage of a caged mouse.”

Still, by 1985 Prince had won two Grammys, an Oscar (for the soundtrack to “Purple Rain”), released an album that topped the Billboard charts for three consecutive weeks, and publicly declared he had retired from touring.

That pronouncement, like many that Prince made over the course of his career, turned out to be short-lived, overruled by his own boundless creative energy. By 1987, he was touring again, behind a new geyser of music that included the albums “Parade” and “Sign O’ the Times,” considered by many to be his best. While this next run of material kept sexuality at the forefront, the songs also featured a powerful focus on political themes, with songs alluding to nuclear war and AIDS.

By the end of his career, he had released 39 studio albums, 16 of which went platinum. He also released 19 Top 10 singles on the Billboard Hot 100. He was inducted to the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame the first year he became eligible. “These numbers are impressive, but frankly, his true impact is completely immeasurable,” James Donio, president of the Music Business Association, said in a statement Thursday.

The freedom and boundary-breaking in his music was matched by his ferocious drive to protect his intellectual property. In the early 1980s, Prince formed his own record label, Paisley Park, which Warner Bros. distributed. That deal ultimately soured, and in 1994, just two years after naming Prince a vice president, Warner decided it would no longer distribute Paisley Park’s material. Prince launched an ugly fight to extricate himself from the major label, likening his contract with the label to slavery before the two finally parted ways in 1996. In 2013, he returned to Warner, on condition that he regain ownership of his back catalog.

That protectiveness also put him at odds with how the world began to consume music. Prince kept his music off iTunes for as long as he could, and filed numerous lawsuits against people who posted his music on YouTube, including one landmark case where he sued a woman who uploaded footage of her daughter dancing along to his hit, “Let’s Go Crazy.” That case wound up setting a precedent for fair use on the internet.

By the end of last year, Prince had begun to come around to the possibilities of streaming. He added his catalog to Tidal, the only streaming service to get access to it, and shared his two most recent albums there.

While those albums, along with the music he made in his later years, failed to register in the same seismic way as his earlier material, Prince never slowed down. In the days before he died, he was busy touring, playing through his catalog with nothing more than a piano, and readying a new album, which would have been his fortieth.

“I don't live in the past,” he told journalist and longtime Prince-watcher Neal Karlen in 1985. “I make a statement, then move on to the next.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.