Researchers Identify Where Stress Emanates In The Brain

Being stressed out is a very common human experience. Although stress is felt ubiquitously, the neurobiological mechanisms underlying such an experience have remained a mystery.

The ill-effects of high subjective stress include negative long-term consequences for mental and physical health, alongside detrimental effects on cognition. Therefore, there is a need to understand how these feelings arise and the role of the brain networks underlying this core human experience.

In animal models, researchers have identified brain networks that support the physiological responses to stress.

“We can’t ask rats how they are feeling,” Elizabeth Goldfarb, an associate research scientist at the Yale Stress Center and lead author of the study told Yale News.

Yale researchers have now discovered a neural home of the feeling of stress and this could help individuals deal with the debilitating sense of fear and anxiety that stressful feelings can evoke.

The study:

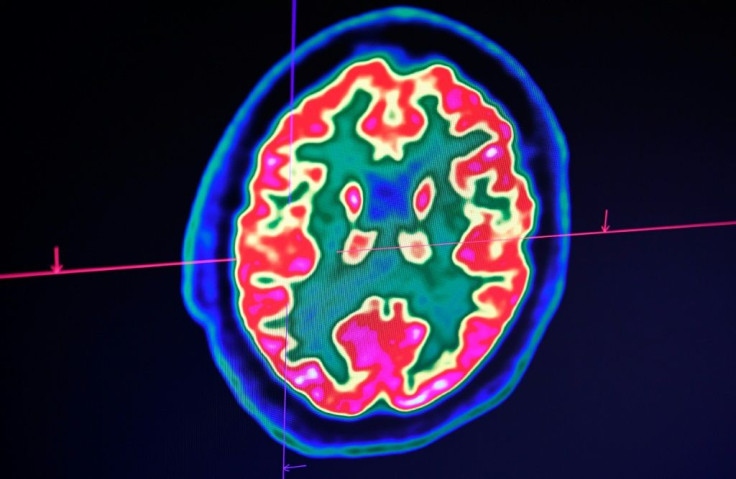

The researchers conducted a series of fMRI scans on people who were asked to quantify their stress levels when they saw troubling images including a snarling dog, mutilated faces, or filthy toilets.

Their findings revealed the following:

- Neural connections arising from the hippocampus region of the brain while viewing such troubling images not only reached the areas of the brain linked to physiological stress responses but also to those that are associated with higher cognitive functions and emotion regulation.

- When neural connections between the hippocampus and frontal cortex regions of the brain were stronger, the study participants reported feeling less stressed by troublesome images.

- Conversely, the study participants felt more stressed when the neural network between the hippocampus and hypothalamus was more active.

- People suffering from mental health conditions including anxiety might have difficulty receiving calming feedback from the frontal cortex regions of the brain during stressful times.

“These findings may help us tailor a therapeutic intervention to multiple targets, such as increasing the strength of the connections from the hippocampus to the frontal cortex or decreasing the signaling to the physiological stress centers,” Rajita Sinha, the Foundations Fund Professor of Psychiatry, and a professor in Yale’s Child Study Center and neuroscience department told Yale News.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.