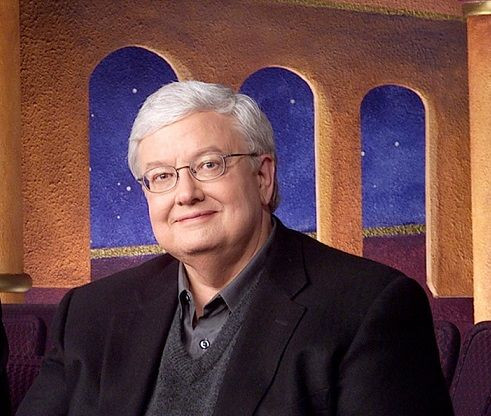

Roger Ebert And The Day Film Criticism Died: Movie Critic's Death Symbolizes The End Of A Profession

The death of legendary film critic Roger Ebert on Thursday has elicited an outpouring of emotion from Hollywood, the media industry and the public at large. From actors and directors to fellow critics and journalists, admirers of the Pulitzer Prize-winning cineaste wrote articles, blog posts and tweets expressing their grief. They lament the passing of a singular voice in American journalism, a movie critic who rose to the top of his craft -- and then broke the ceiling.

But perhaps the saddest thing about Ebert’s death is that there is no one left to take his place. No prominent film critic working today -- not A.O. Scott, Anthony Lane, Peter Travers, or anyone else -- is likely to take up the mantle of “the world’s preeminent film critic” now that Ebert is gone. It’s not just because they could never fill his shoes; it’s because there are no such shoes left to fill.

Ebert was the last of a now-extinct breed: a professional movie reviewer whose opinion actually mattered -- not mattered in a Rex Reed sense, where calling Melissa McCarthy a hippo can nab some headlines and rile people up on social media, but mattered in the spirit of public intellectuals like Jean-Paul Sartre, who believed his chief duty was to observe the world and speak out in accordance with his own conscience. If that type of conviction still exists, it’s been drowned out by Rotten Tomatoes, online trolls and the comments section on Comingsoon.net. Crowd-sourced criticism is calling the shots now, and if a movie has any hope of surviving beyond its opening weekend, it needs positive Facebook chatter and a pithy hashtag campaign. What it doesn’t need is a slew of glowing reviews from professional tastemakers, as evidenced by the inexplicable box-office success of “Oz the Great and Powerful.”

As for Ebert, whether you agreed with his tastes or not (Is "Herzog" really the apex of cinema?), it’s safe to say that there will never be a time again when a single movie critic will exert as much influence as he did in his day. Ebert and his contemporaries -- Pauline Kael, Gene Siskel -- wielded their pens at a time when print media set the national conversation and movies sat at the top of the cultural totem pole. Today, most newspapers are struggling for survival while the average moviegoer visits the cinema fewer than six times a year. Is it any big surprise that those who write about movies for a living have lost much of their clout to people with higher Klout scores?

Film criticism has been dying a slow death for years, and Ebert’s own slow death -- a decade-long battle that robbed him of his ability to speak -- encapsulated that. People who work in media know this. We’ve seen, in recent years, a number of prominent film critics ousted from legacy publications that no longer see value in what they do. Todd McCarthy at Variety, J. Hoberman at the Village Voice, the list goes on and on. Ebert himself posted an angry rant about McCarthy’s firing in 2010, writing that “if Variety no longer requires its chief film critic, it no longer requires me as a reader.” The fact that the mighty trade paper has since been sold to a digital publisher for a fraction of what it was once worth might seem like a nice bit of karmic payback, but the truth is, it’s not Variety’s fault that the world has changed.

To be sure, film criticism, like film itself, will always matter to some of us. We appreciate thoughtful analysis and an informed opinion, and we’ll love the movies until our dying day, even if the CGI-laden drivel being churned out by Hollywood refuses to love us back. The problem is, our numbers are dwindling. Anoint as we might a worthy Ebert successor, what chance does he or she have at breaking into the cultural mainstream in the way that Ebert did? How does one define a zeitgeist when none exists?

As the chief film critics for the New York Times, A. O. Scott and Manohla Dargis are the most likely candidates to fill Ebert’s position, but it’s hard to imagine either of them attaining “preeminent film critic” status in a world where the status of both film and criticism is in a state of free fall. When Roger Ebert died, he took with him the very soul of his profession. And that’s the biggest thumbs-down of all.

Got a news tip? Send me an email. Follow me on Twitter: @christopherzara

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.