Secondhand Chemo Is Real: How Jim Mullowney Is Dealing With ChemWaste Crisis From Both People and Business Point of View

There are hidden costs in modern cancer treatment that few are willing to talk about, and fewer still have the courage to solve. But for Jim Mullowney, CEO and founder of Pharma-Cycle, ignoring them is not an option. After nearly two decades battling regulatory resistance and institutional silence, he's created a business-ready solution with the potential to transform how chemotherapy waste is handled, not just as a healthcare imperative, but as a smart, scalable business move.

"People ask, 'Who's going to pay for it?'" Mullowney says. "And I always say: it pays for itself."

At the center of Pharma-Cycle's innovation is a patented packaging system designed to safely collect and manage human waste contaminated by chemotherapy drugs, waste that continues to emit cytotoxic chemicals long after a patient leaves the clinic. Mullowney, with a background in hazardous and medical waste management, was uniquely positioned to spot the blind spot in the system. "There's over a $40 billion hazardous waste industry and around a $39 billion medical waste industry," he explains, "but the space in between, the overlap, was being completely ignored."

That blind spot comes at a price. Chemotherapy drugs don't just pass through the human body harmlessly. In fact, most of those chemicals are excreted in urine, feces, and sweat within days of treatment. These cytotoxics, designed to destroy rapidly dividing cancer cells, pose serious risks to non-cancerous cells, too, especially for caregivers, healthcare workers, and family members.

Mullowney's TED Talk, We Put a Man on the Moon, But Can't Solve This?, explores the dangers of what he calls "secondhand chemo." It's not just an abstract concept; it's personal. His daughter was three when he first started noticing the gap in oversight. "I had guys in my warehouse opening drums with syringes filled with some of the most dangerous chemicals ever invented," he recalls. "At the same time, my daughter was playing in the next room. That's when it became real."

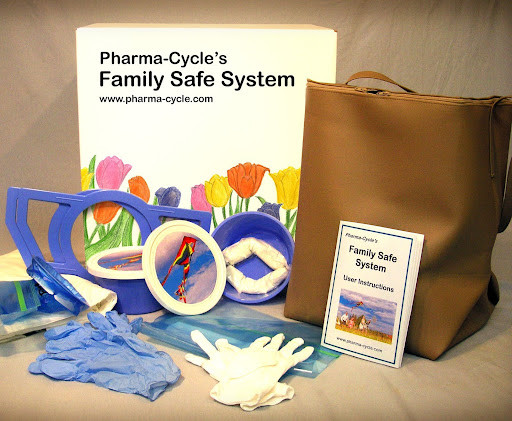

Pharma-Cycle's solution is deceptively simple: a two-foot square kit shipped directly to patients undergoing chemotherapy. Each kit includes everything needed to safely collect waste for two days post-treatment. The package is stabilized, odorless, and secure, and is returned via parcel services for proper disposal. It protects not only the patient's family but also the environment, especially in rural areas where many homes rely on septic tanks and wells, allowing cytotoxic waste to leach into groundwater.

What Mullowney is pushing for is a shift in the standard of health care. He believes these waste kits should be bundled with the drugs themselves, just like sharps containers are with injectable medications. "We are not asking to replace chemotherapy," he says. "We are saying, if you are going to send people home with these drugs in their bodies, you need to send them home with a way to protect everyone around them."

It's a bold task, but not without traction. Mullowney has been in conversations with several major pharmaceutical companies and international healthcare leaders. "We have had discussions with some of the largest players in the industry," he says. "There's interest. They understand the problem. But the question always comes back to cost."

That's where the business case comes in. From potential lawsuits against hospitals for occupational exposure, to the environmental fines and water contamination risks, to long-term generational health effects, ignoring chemo waste is not just dangerous. It's expensive. "You don't need to care about public health to see the ROI here," Mullowney points out. "You just need to care about your bottom line."

The pharmaceutical industry has been slow to respond. Regulatory bodies are even slower. Mullowney was ignored by policy-makers. At times, he's been accused of being "just in it for the money" because Pharma-Cycle is a for-profit company. But his motivations could not be more personal.

He says, "I'm in this because I couldn't stand the idea that families, my family, could be exposed to something so dangerous and not even know it."

After personal setbacks, including a years-long legal battle and the loss of his historic family home, Mullowney is doubling down on his mission. "I'm back," he says. "And I need people to listen. Not because I'm angry, but because this is solvable. We can do something about it right now."

Pharma-Cycle is currently re-engaging with potential partners and investors. The system is patented, operational, and already supported by major logistics networks. The science is there. The risk is clear. And the market, cancer care, is unfortunately only growing.

"This is not about whether chemo should exist," Mullowney says. "It's about how we manage its aftermath. If we can control exposure in the lab, if we use robots to compound these drugs in million-dollar cleanrooms, why are we sending people home to excrete them into their sheets and their families?"

The answer is not more awareness campaigns. It's infrastructure. And with Pharma-Cycle, the infrastructure exists.

"We solved the technical problem," Mullowney says. "Now, we just need the will to implement it."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.