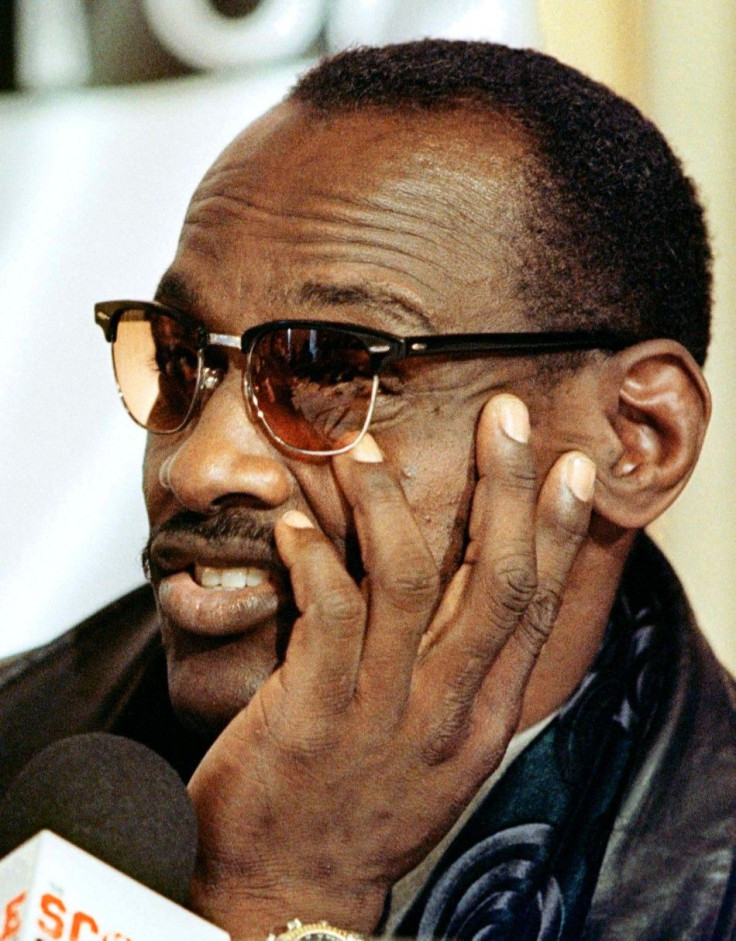

Walter Payton Book Review: A Bit of ‘Sweetness’ Goes a Long Way

Sweetness: The Enigmatic Life of Walter Payton has provoked mixed reactions from fans of the late Chicago Bears running back. Payton's abuse of painkillers, fathering a child out of wedlock, and the depression he felt when his professional football career was over are aspects of his life that had not yet been explored, and were found unwelcome knowledge by some.

Indeed, it would have been far easier for author Jeff Pearlman to just stick with writing about Payton's professional football career. But Pearlman does a huge service to fans, as he goes through the various phases of Payton's life in explicit detail, from his days as an African-American kid growing up in the South during the country's transition to desegregation to his time at Jackson State College (today's Jackson State University), to his post-NFL life.

One of the qualities that Pearlman captures especially well is the younger Payton's sense of humor, which makes for several laugh-out-loud moments in the book. One is when Payton, newly-recruited into the NFL, and his agent, Bud Holmes, decided to mess with sportscaster Brent Musburger and Bears officials by pretending they were a couple of small-town bumpkins.

Pearlman describes the way Payton and Holmes acted when disembarking from a plane in Chicago's Meigs Field on a cold winter day right before meeting Musburger for an interview:

He stuck his head out the door, crinkled his nose, and screamed, Uh-uh, no way. I ain't playing in this mess. What is that stuff? Is that cotton?

No Walter, Holmes said. That's snow.

Snow! said Payton. Well, I ain't ever seen that before.

Boy, bellowed Holmes, get your ass off that airplane!

Uh-uh, Payton replied. I ain't stepping into that mess. Mama told me I could come back to the house if I don't like it here. I wanna to go on back home now, Mista Bud.

Having never prepared for a life that did not include playing football, Payton is seen sort of milling about after his retirement, trying to figure out ways to save himself from boredom. He is seen taking over a variety of ventures, from restaurant ownership to racecar driving. He continued to pursue a multitude of women and ignore a son he fathered out of wedlock while maintaining his public image: that of a devoted father and husband.

To this effect, one of the most suspenseful parts in Pearlman's book is about Payton's induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. What was supposed to be a great honor turned into a nightmare. Payton's lover at the time, a woman Pearlman identifies by the pseudonym Lita Gonzalez, insisted she attend the event as his girlfriend. Payton's wife, Connie, would be there as well.

Payton's longtime assistant, Ginny Quirk, whom Pearlman credits on his Web site as one of the major keys to his book, was in charge of the details.

Four full days, she said, Pearlman wrote. Four full days, and Lita and Connie were like two ships passing in the night. If Connie was scheduled to come late, I'd make sure Lita was there early. If Connie was coming early, Lita would be there late. I can't describe the horror of that trip. It was the worst thing ever.

Pearlman writes that Quirk and Kimm Tucker, the head of Payton's foundation, were Payton's closest confidantes when his football career was over. They and Holmes spoke to Pearlman of Payton's mood swings, suicide threats, and the times he would call them in various states of mind.

Pearlman wrote: It was like having a husband, said Tucker, without the intimacy. He was terribly lonely. People loved Walter. People were drawn to him. But he never had the love of a partner who filled him up. It was tragic.

Pearlman's findings yielded several contradictions made by Payton's wife, Connie, and even by Payton himself. Pearlman noted that Connie and her husband did not, as she has said on numerous speaking occasions, have a loving marriage. He wrote that Linda Conley, a friend of Payton and his family, told Connie about her husband's out-of-wedlock son and suggested she talk to him about it before he passed away.

She told me she'd once asked Walter if he had any other children, and he said no, she recalled. Connie said she believed him. I don't see how she could have, but she said she believed him. Maybe she just didn't want to believe the entire truth, because it killed her whole narrative.

Pearlman's more controversial revelations of Payton may stir up feelings of loyalty, and a bit of antagonism, in die-hard Payton fans, but he has done them a huge service. The book goes into the darker aspects of Payton's life, but there is also much good in it, making for a compelling read. Pearlman explores the Walter Payton who never turned down a fan, the Walter Payton who acquired autographed sports memorabilia to raise money for sick children, the Walter Payton who liked to joke, and the Walter Payton who never gave up hope when he became sick.

I love him, Pearlman wrote in his acknowledgements. I love what he overcame, I love what he accomplished, I love what he symbolized, and I love the nooks and crannies and complexities.

Half of the truth about Payton would have been interesting, but to read the whole truth has been fascinating.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.