Crafty Commonwealth: Canada, UK To Share Foreign Embassies, Not Policies

At first glance, Canada and the United Kingdom don’t seem like strange bedfellows. But a new union between the two sovereign states could go less smoothly than expected.

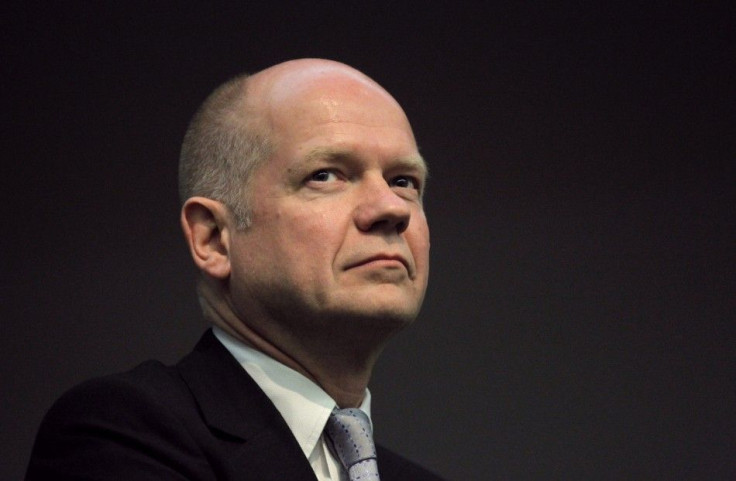

UK Foreign Secretary William Hague traveled to Ottawa on Monday, where he will announce a plan to share foreign embassy and consulate buildings with Canada.

He called Britain and its former colony, which still has the queen as its head of state, “first cousins” on Monday.

“We have stood shoulder to shoulder from the great wars of the last century to fighting terrorists in Afghanistan and supporting Arab Spring nations like Libya and Syria,” Hague told Agence France-Presse reporters in Ottawa, adding that joining embassies would be a cost-saving move.

Officials have not specified where these joint embassies and consulates will be, so details remain vague. Statements so far indicate that if either country builds an overseas consulate or embassy from now on, the efforts, costs, and space may be shared if it is mutually beneficial. Staff at these joint facilities may collaborate on administration and security, but there is to be no increased diplomatic coordination.

It all sounds practical enough, but this consolidation involves more than finding someone to share the rent. In terms of diplomacy, Canada could be getting the short end of the stick -- but budgetary woes leave little in the way of alternatives.

Kicking the Relationship Up A Notch

The decision to share office space is not entirely unprecedented. British and Canadian diplomats already share space in Mali, for instance, where the embassy in the capital city of Bamako is technically under Canadian control. The reverse is true in Myanmar, where Canadian diplomats work within the walls of the British Embassy in Yangon. Some other nations also share facilities; the most famous example is the sprawling, glass-paneled complex called the 'Nordic Embassies' in Berlin, which houses diplomats from Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden.

Furthermore, Canada and Great Britain already share formal governmental links. Both are members of the Commonwealth of Nations, a 54-member collection of sovereign nations, successor of the Britsh Empire, that operates under a set of guidelines for democracy and human rights, as outlined in the Singapore Declaration of 1971.

The two countries even have a monarch in common. Queen Elizabeth II heads the Commonwealth and is the nominal head of state for 16 countries, including the United Kingdom and Canada.

But in terms of diplomacy, Canada is keen to defend its sovereignty. Unlike the United Kingdom, it has no history of colonialism and is rarely interventionist when it comes to foreign affairs.

Despite the exhortations of then-British Prime Minister Tony Blair in 2003, for instance, Ottawa refused to join the invasion of Iraq, offering non-combat assistance instead. Canada did contribute to NATO forces in Afghanistan beginning in 2001; it currently has about 500 troops there. The United Kingdom has 9,500.

These differences have some experts, like Canada’s representative to the United Nations Paul Heinbecker, wondering whether diplomatic cohabitation is a good idea.

“The idea that we have a sufficient amount in common with the British that it makes sense that we share premises as a matter of routine, that, I think, is a mistake,” he told the Globe and Mail of Toronto, adding that such an arrangement would not benefit Ottawa.

“We have an incompatible brand with the U.K.”

Taking a Sacred Vow

Embassies are more than buildings to house diplomats’ offices. They are a physical manifestation of the relationship between sovereign nations, and are therefore as symbolic as they are functional. No wonder that the current wave of protests in the Middle East, which erupted largely in response to an offensive film produced on American soil, has centered around Western embassies.

Building or removing an embassy in a foreign nation is therefore a matter of great diplomatic significance.

In May, for instance, the United Kingdom announced new plans to open an embassy in Haiti and reopen a closed venue in Paraguay, as part of a larger effort to build ties in the Caribbean and Latin America. (It is possible, though not confirmed, that Canadian diplomats will make use of these facilities in accordance with Monday’s agreement.)

On the flip side, both the United Kingdom and Canada have lost embassies in Iran due to an increasing disharmony between the Islamic Republic and the Western world. Canada announced a decision to shut down its own Tehran embassy earlier this month, citing the Islamic Republic’s support for the Syrian regime, among other offenses. The United Kingdom lost its own Tehran embassy last year when an informal militia stormed the building to protest British sanctions.

If the removal or addition of embassies is so diplomatically significant, could the UK-Canada combination of embassies herald something important, like a stronger alliance or a consolidation of power?

Some think so.

Working Out the Differences

The United Kingdom is far smaller than Canada in area, but larger in both population and national GDP. That gives London far more international clout than any of its Commonwealth ‘cousins’ could hope for.

That’s exactly why some have criticized the embassy-sharing plan -- it could conflate the two countries’ diplomatic identities and thereby diminish the independence of Canada, which is by no means in accordance with the United Kingdom on every foreign policy issue.

There are indeed whispers that the consolidation was designed to strengthen British influence -- not to the detriment of Canada, but of the European Union. (Though the United Kingdom is a member of the EU, it has not adopted the euro and is keen to maintain its status as an independent global power.)

The EU has already pursued diplomatic consolidations of its own, launching the European Union External Action Service in 2010. This body has delegations in countries all around the world.

One unnamed British diplomat told the Daily Mail that the plan to join forces with Canada would eventually also include Australia and New Zealand -- these countries, too, claim Queen Elizabeth as the official head of state.

“For all the grandiose talk of European unity, we have so much more in common with many Commonwealth countries than the EU-- and not just the English language,” said the diplomat.

“There is a saying in the British diplomatic corps that ‘the French want to do us over, the Germans want to lord it over us and the Italians are all over the place.’ We would never dream of trusting them with intelligence secrets, but we share everything with the Canadians, Aussies and Kiwis.”

But other British sources have denied these motives, and there is no reference to Australia and New Zealand in official comments about the embassy-sharing agreement.

Instead, argue Hague and other supporters of the plan, this is a smart way to cut costs and share resources in the middle of a global recession.

Both Canada and the United Kingdom are making big cuts to their foreign affairs budgets, according to the Globe and Mail. Ottawa needs to save $170 million this year, while London is looking to slash $160 million. But neither country wants to dilute its presence in emerging markets around the world, most notably in Asia, where more consulates will ease the transfer of people and investments.

In short, it’s all about the bottom line. Critics of the plan worry that this will inhibit Canada’s century-long effort to emerge from the colonial shadow -- but the tighter funds are, the harder it is to argue on principle.

As Hague asserted on Monday, “It is natural that we look to link up our embassies with Canada’s in places where that suits both countries. It will give us a bigger reach abroad for our businesses and people for less cost.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.