Food Stamps May Be Cut, But Here’s An Ad For Wendy’s: Twitter Searches Reveal Promoted Tweets Fail

News that House Republicans voted to cut $39 billion from the federal food-stamp program over the next decade has no doubt sent many concerned recipients searching for more information on the Internet. But if they’re searching on Twitter, they might be inadvertently adding insult to their injury.

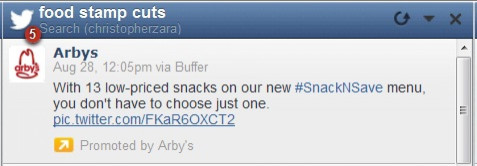

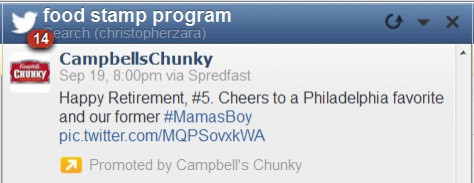

Twitter searches for “food stamps” and related terms are calling up promoted tweets from various food companies, restaurant chains and other food-related services, all without the slightest hint of awareness that many people searching for those terms may not be able to afford food.

The Campbell Soup Company (NYSE: CPB), Wendy’s Co. (NASDAQ:WEN) and the privately held Arby’s Restaurant Group Inc. are just a few major companies whose products and services are being hawked alongside searches such as “food stamps,” “food stamp cuts” and the like. One search turned up a photo of a bowl of Campbell’s SpaghettiOs and a tweet asking, almost mockingly, “Who is grabbing a snack this afternoon?”

Ads for Seamless, a privately held food-delivery service, were also plentiful. Searches for “food stamps” called up several promoted tweets from Seamless attempting to whet our appetites with guacamole and peanut butter and jelly puffs. One search for “food stamp drug testing” called up a Seamless ad saying, “Let’s make dinner awesome tonight. Shall we?”

Twitter Inc. describes promoted tweets as “ordinary Tweets paid for by advertisers who want to reach a wider group of users or to spark engagement from their existing followers.” The tweets reach users through a combination of targeting systems that use keywords, interests and Twitter usernames. Advertisers can also target users based on location, gender and the devices they use.

In this case, it’s clear that the keyword “food” is calling up the food-related ads from companies that did not anticipate searches for “food stamps.” And that could have been avoided, according to Twitter spokesman Will Stickney, who said companies have it within their power to avoid sending poorly targeted tweets that could be deemed offensive.

“We give advertisers three different matching options when entering keywords: exact match, phrase match, and basic keyword match,” he told International Business Times in an email. “We also allow for negative keyword match, so you can enter terms like ‘food’ but not ‘foot stamps,’ but it’s all up to the advertiser on how they manage those terms.”

Promoted tweets are the most pivotal component of Twitter’s business model. Their functionality, and in particular their limitations, will be under increasing scrutiny over the next few months as Twitter approaches its highly anticipated IPO. A food-stamp recipient worried about going hungry being ambushed by a picture of a ham sandwich will unlikely wield much influence over the perceived value of promoted tweets, but it does highlight how far Twitter still has to go before its targeted ad systems are on par with those of Google Inc. (NASDAQ:GOOG) or even Facebook Inc. (NASDAQ:FB). Search for “food stamps” on Google and you will likely see a Google ad related to food stamps.

The potential consequences of poorly targeted ads are not hypothetical, by the way. Earlier this year, Facebook faced a huge backlash from feminists and women’s groups who said the social network was too lax on posts that promoted violence against women and girls. In a massive boycott effort, the groups targeted Facebook advertisers, letting them know that their ads were appearing alongside offensive memes and rape jokes. Many of the companies, including Nissan Motor Co. Ltd. (OTCMKTS:NSANY) and the Zipcar unit of Avis Budget Group Inc. (NASDAQ:CAR), said they simply didn’t have enough control over where their ads appeared throughout the site. Facebook ultimately agreed to reevaluate its policies, but only after advertisers, recoiling from the bad publicity, started dropping out.

That’s unlikely to happen in Twitter’s case, but considering how quickly a poorly targeted ad can turn against a company, and how much Twitter relies on promoted tweets, it should be food for thought.

Got a news tip? Send me an email. Follow me on Twitter: @christopherzara

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.