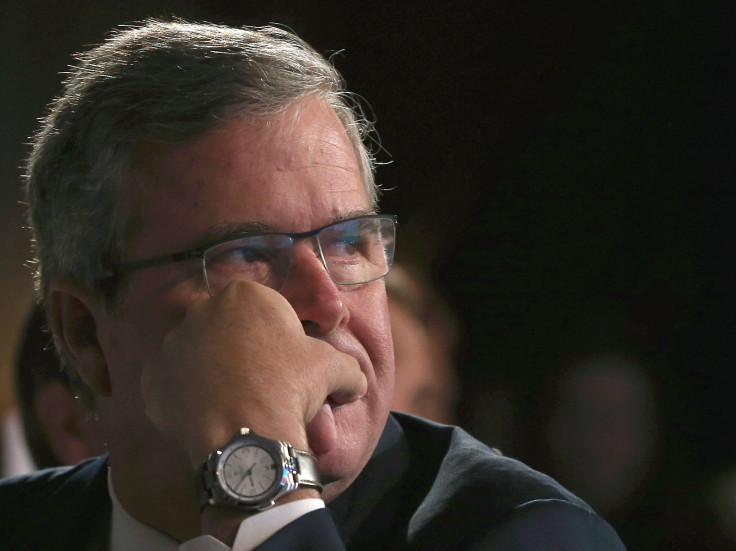

Jeb Bush Pressed Pension Officials On Behalf of Donor's Firm

Jeb Bush received the request from one of his campaign contributors, a man who made his living managing money: Could the then-governor of Florida make an introduction to state pension overseers? The donor was angling to gain some of the state’s investment for his private fund.

It was 2003, still a few years before regulators would begin prosecuting public officials for directing pension investment deals to political allies. Bush obliged, putting the donor, Jon Kislak, in touch with the Florida pension agency’s executive director. Then he followed up personally, according to emails reviewed by the International Business Times, ensuring that Kislak’s proposal was considered by state decision makers.

Here was a moment that at once underscored Jeb Bush’s personal attention to political allies and his embrace of the financial industry, which has delivered large donations to his campaigns. Email records show it was one of a series of such conversations Bush facilitated between pension staff and private companies at a time when his administration was shifting billions of dollars of state pension money -- the retirement savings for teachers, firefighters and cops -- into the control of financial firms.

Florida officials say Kislak’s firm was not among the beneficiaries of that shift. But verifying that assertion is virtually impossible for an ordinary citizen by dint of another hallmark of Bush’s governorship: At the same time that he entrusted Wall Street with Florida retirement money, he also championed legislation that placed the state’s pension portfolio behind a wall of secrecy.

The legislation, which Bush signed into law in 2006, shields key details of the state’s pension investments from Florida's open records statutes. The exemption benefited the financial sector -- the area of the economy that would ultimately employ Jeb Bush upon his leaving office. The law prevented pensioners, legislators and taxpayer groups from scrutinizing pension holdings or authenticating state officials’ statements about investments. It also impedes campaign finance watchdogs and political reporters from discovering whether Bush’s prospective 2016 presidential donors in the finance industry were the recipients of Florida pension deals.

Advisers for Bush did not respond to questions from IBTimes.

Two former Florida governors told IBTimes that Bush’s direct role in facilitating conversations between state pension overseers and firms seeking to manage pension funds breaches the norms of ethical government.

“You have to be careful not to delve in that arena,” said former Republican Gov. Charlie Crist, who as Florida attorney general served with Bush as a pension trustee. Crist switched parties to become a Democrat in 2012.

Former Democratic Gov. Buddy MacKay, who was defeated by Bush in 1998, said it “would have been considered out of bounds” to set up conversations between Florida pension officials and corporate executives seeking state investments. Doing so, he added, “would lend itself to people questioning whether that was undue influence.”

In recent weeks, as his expected entry into the presidential race approaches, Bush has portrayed himself as an ardent proponent of transparency in government. He pointedly criticized former Obama administration Secretary of State Hillary Clinton -- the near-presumptive Democratic nominee -- for handling her official correspondence with a private email address stored on a private server in her home. “Transparency matters,” Bush declared, touting his decision to release thousands of his own emails from his tenure as governor.

But some suggest that his own handling of Florida’s $149 billion pension fund -- the fourth largest in the country -- contradicts that talk, indicating that Bush himself is fond of secrecy when it serves his own political interests.

Republican Curtis Loftis, treasurer of the crucial GOP primary state of South Carolina, said Bush’s push for the exemption that let his appointees forge secret pension deals belies the former governor’s stated commitment to open government.

“Anyone running for president must reconcile their present pro-transparency statements with their previous positions, and signing laws that allow small groups of unelected bureaucrats to do business with Wall Street in a way that is completely opaque is bad business and very difficult to reconcile,” Loftis told IBTimes.

Crist said of the effort to exempt Florida’s pension investments from open records laws: “The public has a right to know what things are being invested in.”

The Bush administration's push to shift pension money to private firms came as public retirement systems all over the country were beginning to move state employees’ savings into private equity, venture capital, hedge funds, real estate and other “alternative investments” that beckoned with promises of greater returns in exchange for amplified risks and higher fees.

Bush’s moves also came amid heightened scrutiny of public officials using pension money to reward campaign contributors. Only a few years after he left office in 2007, high-profile pension corruption prosecutions in New York prompted the Securities and Exchange Commission to pass a federal rule effectively banning state and municipal pension investments in firms run by public officials' donors.

Bush himself seemed aware of the issues inherent in that future “pay-to-play” rule, telling the Miami Herald in 2003 that as an elected official, he “shouldn’t know about” individual pension investments so as to prevent political considerations from driving investment decisions.

But only a week after that interview, Bush arranged the conversation between Kislak and Florida pension officials, according to emails.

Those emails were among many showing Bush playing an active role in shaping Florida’s portfolio as the most prominent of three State Board of Administration (SBA) trustees who oversaw the pension system.

"Bush was always informed as to decision making around asset allocation, and took a leadership role in that area,” said Tom Herndon, who served as executive director of the SBA under Bush. “He wanted to be briefed fully on everything that was happening at the fund. He had always done his homework. He did a great job overseeing the fund, and was proactive in knowing as much as possible about what we were doing."

The strategy pursued by the Bush administration involved investing Florida pension money through opaque vehicles known as funds of funds -- essentially, pools of money that comprise pieces of other funds. The administration's larger shift into alternative investments fell short of the returns for retirees projected by state officials, but did benefit one well-positioned group: It generated millions of dollars worth of transaction fees paid during Bush’s time in office to private financial firms that won contracts to manage public pension money.

One of the financial firms interested in that lucrative state business was Milcom Venture Investments, a Maitland, Florida-based company seeking to commercialize military technologies. In 2001, the firm’s president, Matt Bigge, was one of a number of private equity investors who met with Bush to talk about venture capital. In an email after the meeting, Bigge told Bush: “As a fellow border-line libertarian, I wholeheartedly concur with your belief that the market, not government, should dictate the shape and complexion of the economy.”

Despite that libertarianism, Bigge then pushed Bush to direct government pension money into a “venture capital allocation.” He also informed the governor that he was interested in having the Bush administration invest public employees’ retirement money in his company, telling the governor that the firm would like an “opportunity to make the state some money.”

“Thank you Matt for coming up to Tallahasse [sic] to lend a hand,” Bush wrote back, blind-copying Coleman Stipanovich, who succeeded Herndon as the pension agency’s executive director. “Let me know how I can be of assistance for Milcom.”

That year, Bush also received an email from Kislak, who had previously served as a deputy undersecretary in the Department of Agriculture during George H.W. Bush’s presidential administration. Kislak wrote that his business partner at Antares Capital Corp. had recently met with SBA staff and discussed a proposal to invest pension money in venture capital firms in Florida.

“I certainly agree that Florida's State Board of Administration should have an exposure to venture capital as part of its alternative asset class,” Kislak said, urging Bush to support the plan. “In addition to Antares,” Kislak added, “there are other Florida-based venture firms with attractive track records and capabilities to properly invest this capital.”

Bush soon spearheaded an initiative to transfer more state workers’ pension money into alternative investments. That shift was endorsed by the SBA in early 2003, when state documents show Bush brushed aside the objections of Crist, who raised concerns about the risks of venture capital investments and cast the lone vote against the overall plan.

Months after that vote -- and one day after the governor and other Republicans gathered in Tampa to launch the Florida branch of President George W. Bush's re-election campaign -- Bush received another email from Kislak.

“What a great presentation last night. It was a wonderful low key presentation of the choice before the country. We are so blessed to have you represent us....your brother, too,” wrote Kislak, who by that point had made maximum $500 contributions to both of Bush’s gubernatorial campaigns, $3,000 to his brother’s presidential campaigns and $16,100 to the Republican Party of Florida.

“You suggested I contact you about our newest venture capital fund,” Kislak continued. “I would appreciate it if you could direct us to the proper people to review whether Antares Capital Fund IV would make an appropriate portfolio investment for the State.”

Bush emailed Kislak back and copied the pension agency’s executive director. “I am passing your email to Coleman Stipanovich for his followup,” Bush wrote.

A few weeks after Kislak’s outreach, Bush checked in with Stipanovich, emailing him: “Has this been handled?”

Stipanovich let Bush know he had spoken with Kislak and reported that he “now has a clear understanding of our newly created VC program that will utilize a fund of funds strategy.” Once the state finished deals with the fund of funds managers, Stipanovich said, “we will put a process in place to introduce credible FL based VC firms to these managers.” These firms could then receive funding through a “competitive process,” Stipanovich said.

Bigge and Kislak did not respond to IBTimes' requests for comment.

In 2004, the Florida pension system ratified Bush’s plan to commit $350 million of public workers’ retirement money into venture capital investments. Within months, Bush received an email from Dr. Athanasios Maroglou, then an executive at BioInnovation Partners, after the governor spoke at a biotechnology industry conference. Maroglou told the governor he “would like to take you up on your kind offer to introduce us to the funds of funds selected to invest the Florida pension money into venture capital funds.”

“Thank you for your followup,” Bush replied. “I am asking that Coleman Stipanovich contact you and get the venture firm to contact you as well. Let me know how it goes.”

Stipanovich then wrote to Maroglou, requesting he send information to agency staff, who would pass it along to the Florida-focused fund of funds manager to “begin the review process.”

Maroglou said the investment in his company didn’t materialize. “We never moved forward with that fund,” he said, “because there was no interest at the time of investing into new venture capital companies.”

IBTimes’ attempts to reach Stipanovich for comment were unsuccessful.

During Bush’s two terms in office, Florida more than doubled its investments in private equity, moving a total of over $6.8 billion into alternative investments. The strategy did not deliver outsized gains: While Bush was governor, Florida’s private equity portfolio delivered returns that mirrored those of low-fee stock index funds, but that fell billions of dollars short of the benchmarks set by state officials.

The investments, though, were a jackpot for the financial industry. The number of private equity funds getting pension investments jumped seven-fold during Bush’s governorship (and that does not include other firms getting state business as secondary subcontractors in “funds of funds”). In all, the pension paid almost $1 billion in disclosed financial fees in that time -- including $9.5 million in fees to the four investment firms selected to oversee venture capital projects.

SBA officials say the state did not invest in BioInnovation Partners, Antares Capital or Milcom Technologies. But verifying that assertion, identifying all firms that received state investments and determining whether the governor’s political allies benefited from the fees is all but impossible.

That is partly because Bush’s signature venture capital investment program opted to make its investments through “funds of funds” whereby state money is given to financial managers, and then distributed to other undisclosed financial managers. That built-in opacity was intensified by a Bush-backed law that exempts Florida’s entire alternative investment portfolio from the state’s landmark open records law, thereby allowing the state to conceal most details about these deals.

Bush’s administration was involved in the secrecy initiative from the start. In a 2003 email, a Bush aide informed the governor that administration officials were “working very hard to file legislation that would exempt certain [venture capital] investments at the SBA from the Sunshine Laws.” In another state document obtained through an IBTimes open records request, SBA officials argued that “maintaining the information advantage of highly skilled private equity managers is vital.”

Bush did not just back the concept: He backed a plan to have his administration help organize a corporate lobbying campaign for the bill.

In an email, one of Bush’s aides informed the governor of a proposal “to bring Florida-based VCs up here to spend a day during session lobbying their respective legislators on the need for the SBA to receive this exemption.” The aide told the governor that, with his blessing, the administration would focus on “coordinating the lobbying efforts of Florida-based VCs on the disclosure legislation.”

Bush personally endorsed the aide’s proposal, calling the idea a “good plan.” A bill was introduced that year in the legislature, and a similar one passed unanimously in 2006. By that time, Bush had raised more than $2.4 million from the finance, real estate and insurance sectors for his gubernatorial campaigns, according to data compiled by the National Institute on Money In State Politics.

Since Florida passed its open records exemption, other states have passed similar exemptions for financial firms. At the same time, the legacy of the state's push into alternative investments and Bush's disclosure policies have generated controversy.

State documents obtained by journalist Gina Edwards in 2013 showed that six of Florida’s big private equity investments on the books during Bush's governorship trailed the stock market by more than $1 billion. A Tampa Bay Times investigation concluded that because of Bush’s law, “no ordinary retiree can monitor dozens of private investments bought with $20 billion of public money.” Meanwhile, in 2011, the state used Bush’s open records exemption to try to block state Sen. Mike Fasano, a Republican, from seeing the details of an investment in a firm that had done business with the pension system’s top official.

“I could never understand why they tried to hide from the public what they were investing in,” Fasano, now Pasco County’s tax collector and a Bush supporter, told IBTimes. “I mean, heck, you know more from an investment firm of what they’re investing in than the SBA. Here’s a public entity and you couldn’t get the right time out of them.”

IBTimes asked the State Board of Administration for a list of firms in Florida’s funds of funds, to see if they include any connected to Bush’s business ventures or campaign contributors. State officials declined to release the information, saying the documents are “subject to redaction by fund managers” under the 2006 law exempting them from Florida disclosure laws.

IBTimes asked Dennis MacKee, a spokesperson for the SBA, if retirees should have the right to see all the details of state investments made with public pension money. “As fiduciaries, yes,” he said, but only "within the maximum bounds of [the] law.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.