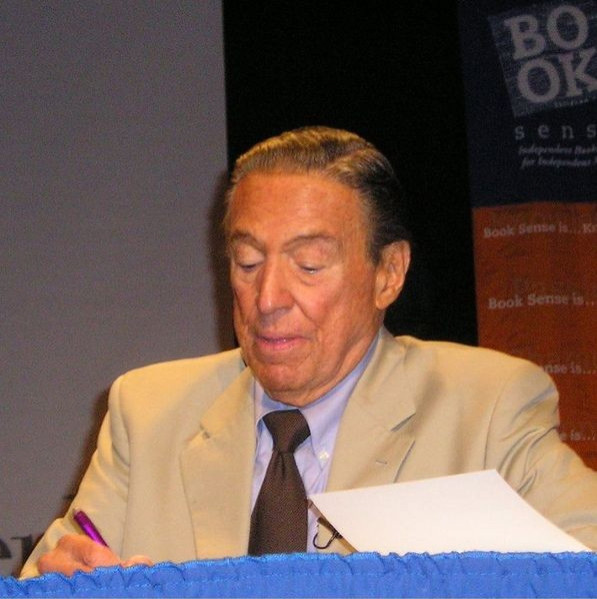

Mike Wallace, TV News Legend, Dead at 93

Mike Wallace, a game show host and tobacco pitchman who went on to personify the hard-nosed and often skeptical journalism of CBS's 60 Minutes, died Saturday after a long illness. He was 93.

Wallace died Saturday night, CBS spokesman Kevin Tedesco said.

He passed peacefully surrounded by family members at Waveny Care Center in New Canaan, Conn., where he spent the past few years, CBS said. He also had a home in Manhattan.

Wallace, who was outfitted with a pacemaker more than 20 years ago, had a long history of cardiac care and underwent triple bypass heart surgery in January 2008, the New York Times reported.

It is with tremendous sadness that we mark the passing of Mike Wallace. His extraordinary contribution as a broadcaster is immeasurable and he has been a force within the television industry throughout its existence. His loss will be felt by all of us at CBS, said Leslie Moonves, CBS president and CEO.

A special program dedicated to Wallace will be broadcast on 60 Minutes next Sunday, April 15.

Wallace built his reputation through sometimes contentious interviews with major and often controversial public figures like Malcolm X, Louis Farrakhan, Muammar Quaddafi, Richard Nixon, Ayotollah Khomeini, Lyndon Johnson, Ronald Reagan, Gen. Manuel Noriega and Gen. William Westmoreland.

His reputation was so fearsome that it was often said that the scariest words in the English language were Mike Wallace is here to see you, as the Washington Post noted.

His late colleague Harry Reasoner once said, There is one thing that Mike can do better than anybody else: With an angelic smile, he can ask a question that would get anyone else smashed in the face.

Occasionally he became part of the controversy. In 1985 Westmoreland sued CBS News after Wallace interviewed him for a special that alleged the military falsified body counts during the Vietnam War. The case was settled during the trial when CBS apologized.

Wallace later said that lawsuit sent him into clinical depression. But he did not back away from the blunt verbal sparring that helped establish the no-nonsense reputation of 60 Minutes, where he and Harry Reasoner were the original coanchors on Sept. 24, 1968.

I had the white hat and the black hat, said the late producer Don Hewitt, who created 60 Minutes. Harry was the guy who came from the heartland and brought Iowa to New York, and Mike was the tough guy in the trench coat.

Wallace eventually became the show's lead correspondent, a position he held until he stepped down to part-time status in 2006.

Among his later contributions, after bowing out as a regular, was a May 2007 profile of GOP presidential hopeful Mitt Romney, and an interview with Jack Kevorkian, the assisted suicide doctor released from prison in June 2007 who died June 3, 2011, at age 83.

In December 2007, Wallace landed the first interview with Roger Clemens after the star pitcher was implicated in the Mitchell report on performance enhancing drugs in baseball. The interview, in which Clemens maintained his innocence, was broadcast in early January 2008.

Critics faulted Wallace for ambush interviews and showmanship, and in 1999 accused him of killing a story on deception in the tobacco industry by giving in to corporate pressure.

In one memorable exchange with Nixon aide John Ehrlichman during Watergate, Wallace said in his trademark staccato style:

Perjury. Plans to audit tax returns for political retaliation. Theft of psychiatric records. Spying by undercover agents. Conspiracy to obstruct justice. All of this by the law-and-order administration of Richard Nixon.

Ehrlichman paused and said, Is there a question in there somewhere?

No, Wallace later conceded.

Conservative groups often called Wallace a poster boy for slanted reporting, with the Media Research Council summarizing his career as too many minutes of liberal bias.

Wallace dismissed this charge many times over the years. In a 2005 interview with his son Chris, a Fox News reporter, he called it damn foolishness.

Many of his industry colleagues seemed to agree. Wallace won 20 Emmy awards, including a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2003. His numerous other awards included three Peabodys and three DuPonts.

Wallace's career was more remarkable because he came to television news relatively late.

Born Myron Wallace in Brookline, Mass., to Russian-Jewish parents, he graduated from the University of Michigan in 1939 and worked in Midwestern radio until he joined the Navy in 1943.

After the war he landed in Chicago radio, where he announced professional wrestling shows and action dramas like Sky King and The Green Hornet.

In the 1950s he moved to New York and hosted a series of CBS television game shows, including the pilot for what would become To Tell the Truth. He also tried his hand as a Broadway actor, with a leading role in the modestly successful 1954 comedy Reclining Figure.

He left CBS in 1955 and launched several late-night interview shows on DuMont, Metromedia and ABC. The most influential would turn out to be Nightbeat, later called one of the first interview shows with attitude because Wallace would ask challenging and sometimes adversarial questions.

Hewitt indicated Nightbeat was one of the elements he incorporated into the concept for 60 Minutes.

Wallace worked in a variety of TV areas into the 1960s, hosting the award-winning Biography series while becoming equally well known as the voice of Parliament cigarettes (a man's mildness).

After the death of his oldest son Peter in a mountain-climbing accident in 1962, he asked CBS for a full-time news position, reportedly taking a dramatic cut in pay, and in 1963 he began anchoring The CBS Morning News.

Wallace's feisty on-air persona could at times be matched off-camera. In 2004 he received a summons for disorderly conduct after allegedly confronting New York police officers who were giving his driver a ticket for double parking.

Wallace wrote two autobiographies, Close Encounters in 1984 and Between You and Me in 2005.

He was married four times. He is survived by his wife Mary, son Christopher and one daughter, Pauline.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.