NYC Salmonella Cases Rise In 2012 Despite Restaurant Letter Grades

[Updated: 10:22 a.m.]

New York restaurant-goers are eating up the city’s three-year-old grading system, but its effect on public health is still a bit of a mystery taste test.

Salmonella infections in New York City rose more than 4 percent in 2012 to 1,168 cases, up from 1,121 cases the year before, according to the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. The uptick follows a much-publicized 14 percent decline in salmonella infections in 2011, the first full year that the letter grades were implemented. City officials had touted the initial decline as an early sign that the letter-grade posting may be contributing to a reduction in foodborne illnesses.

According to city health officials, the annual number of salmonella infections is a useful indicator of trends in food-related illnesses: Salmonella cases occur relatively frequently and about 95 percent of them are believed to be caused by eating contaminated food.

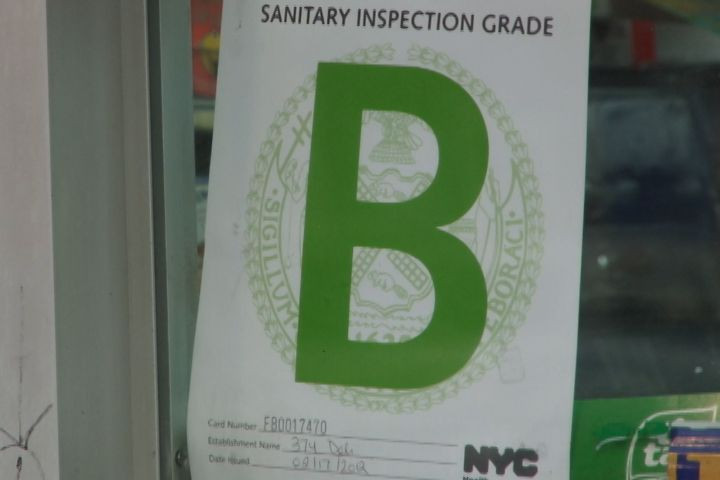

New York’s letter-grading system -- in which restaurants are required to display a large A, B or C grade in the window of their establishment -- was instituted in July 2010. Since that time, the Health Department has published a progress report every six months, updating New Yorkers on the system’s effectiveness. But those reports stopped coming after 18 months: the last one was published in January 2012.

Asked why the reports stopped, the Health Department told International Business Times that city officials “continue to evaluate the letter-grading initiative and are looking at the impact of the improved inspectional program on restaurants and on hospitalizations and emergency visits for foodborne illnesses.”

While popular with the public, the grading system has been described as unnecessarily burdensome and even humiliating by restaurant owners and food handlers who complain of steep fines, arbitrary inspections and bloated hearings procedures.

“I think it really is a punishment for small business,” Patti Jackson, a veteran New York chef, said. “A lot of it is discretionary, and a lot of it is so opaque. A lot of those fines are based purely on judgments by the adjudicators.”

Jackson recalled a time when a restaurant she worked in was cited for multiple violations related to food temperature. According to the city health code, potentially hazardous food requiring cooling must be reduced between 120 to 70 degrees within two hours. In this case, however, Jackson said an inspection was performed within the two-hour window -- the dish in question had just been prepared. But she said the burden of proof was on her to appeal the violation at the city’s Health Tribunal.

“It was a full day of work that was missed to contest things that were not violations of the health code to begin with,” she said.

As Mayor Michael Bloomberg was quick to point out in an interview with New York magazine last month, New Yorkers overwhelmingly support the grading system. But determining whether the letters have any objective effect on public health besides making us all feel better may not be as easy as A-B-C. Salmonella infections are still down when compared to before the grades were implemented, but it’s still early to tell if the uptick in 2012 was more than an anomaly.

Jackson said there has been a national rise in salmonella rates due to such issues as poor processing and cheaply slaughtered feedlot meat, and she doesn’t believe that New York City restaurants can do much to change that outside of what the Health Department already requires. But she acknowledged, too, that many of the city’s restaurants aren't up to snuff, and maybe in the end a little public shaming can’t hurt.

“The grades are punitive and silly, but I don’t think they’re the worst thing that’s ever happened,” she said. “They’re just a giant throbbing pain in the ass.”

Got a news tip? Send me an email. Follow me on Twitter: @christopherzara

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.