Obama Reversal On Offshore Drilling In Atlantic Ocean Reflects Surge In US Shale Oil Production

The Obama administration’s decision Tuesday to cancel plans to drill off the U.S. Atlantic coast was spurred in part by the nation’s onshore oil and gas boom, officials said.

The U.S. Interior Department said it determined that scrapping a proposal for the single oil lease wouldn’t undermine America’s ability to access affordable, reliable energy supplies. Given the surge in onshore shale oil and natural gas output in the last decade, removing the Atlantic lease would lower U.S. oil production by only 0.1 percent, the agency estimated.

“Ensuring energy security even without this lease sale — we have done that,” Abigail Ross, director of the Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, said on a call with reporters. “That’s one of the ways market conditions play into that decision.”

The Interior Department in January 2015 proposed to open much of the southeastern Atlantic coast — including Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia — to offshore drilling for the first time in decades.

In the last year, the agency held nearly two-dozen public meetings and received more than 1 million comments from citizens, business groups, energy companies, elected officials and other federal agencies. Interior Secretary Sally Jewell said Tuesday that most of the feedback raised concerns about drilling in the Atlantic.

Environmental groups and thousands of residents and businesses expressed fears that an oil spill or drilling-related accident could damage ecosystems and disrupt coastal economies. Many drew connections to the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, which smothered coastal states in millions of gallons of oil and pummeled the commercial fishing and tourism sectors. Other critics warned that offshore drilling would undermine President Barack Obama’s efforts to reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels.

The oil and gas industry had broadly supported the Atlantic drilling proposal. Proponents argued the drilling could be done safely and would open up more of America’s vast energy reserves.

The offshore production would add to the explosive growth across onshore oil fields. In recent years, hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, has enabled U.S. producers to grow oil output by nearly 90 percent from 2007 to 2015, federal data show, driving down net oil imports.

U.S. crude production averaged 9.4 million barrels a day last year, with more than half of output coming from fracked wells, the Energy Information Administration said Tuesday. In 2000, by contrast, fracked wells accounted for just 2 percent of total output. While oil output is declining this year as lower oil prices force drillers to scale back, shale production is still expected to double within two decades, BP forecast in February.

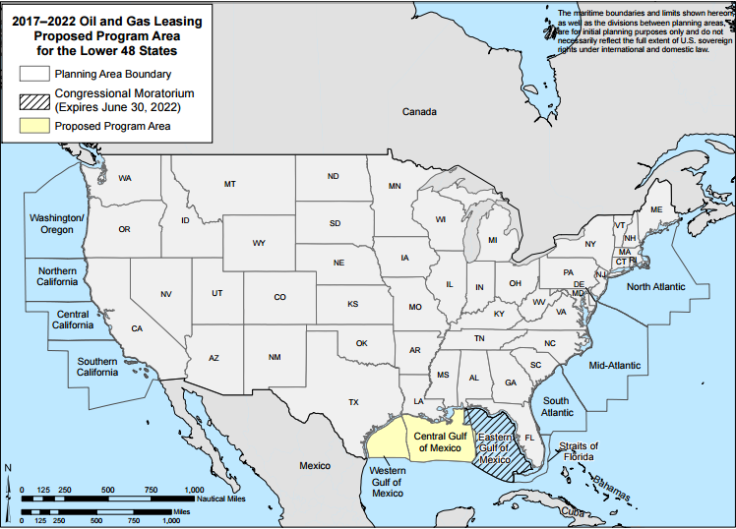

On the press call, Jewell cited the energy market conditions and local opposition as among the reasons for canceling the Atlantic lease plan, which was part of a five-year proposal for the period 2017 to 2022. “This was not the right time for leasing in the Atlantic,” she said.

Supporters of Atlantic drilling rejected the idea that the U.S. onshore fracking boom could offset the need for offshore energy supplies.

Nicolette Nye, a spokeswoman for the National Ocean Industries Association, a trade group, noted that onshore shale wells typically dry up at a much faster rate than larger, offshore discoveries. She added that global oil demand is expected to rise in coming decades as the world population swells and economies expand.

“For the U.S. to truly be a long-term global energy leader, it needs diversification in both energy sources — traditional and nontraditional — and geographical location,” Nye said. “U.S. consumers would be better served by keeping the Atlantic [lease] … and judging the conditions in 2021, rather than taking it off the table in 2016.”

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management manages roughly 5,000 active leases on the outer continental shelf, spanning more than 26 million acres in the Gulf of Mexico, Alaska and the Pacific Coast near California. Last year, the leases accounted for about 16 percent of domestic oil production and 5 percent of domestic natural gas production, the bureau estimated.

Environmental groups hailed the Interior’s decision to scrap the Atlantic lease as a victory for coastal communities and the climate.

“This is a courageous decision that begins the shift to a new energy paradigm, where clean energy replaces fossil fuels, and where we can avoid the worst impacts of decades of our carbon dioxide emissions,” Jacqueline Savitz, Oceana’s vice president for the U.S., said in a statement.

Critics of offshore oil and gas drilling said the fight isn’t quite over. The Obama administration Tuesday upheld its proposal to lease 10 parcels in the Gulf of Mexico plus three lease sales in the Alaskan Arctic, including one sale each in the Chukchi Sea, Beaufort Sea and Cook Inlet. The Interior said it expected to finalize its “proposed program” for the outer continental shelf later this year.

“We’ll continue fighting any new drilling moving forward,” said Rachel Richardson, program director for the drilling program at Environment America. She added the canceling the proposed leases in Arctic and Gulf waters would solidify Obama’s legacy on climate change in his last year in the White House.

“He has a really great opportunity to demonstrate the need to keep [fossil fuels] in the ground, and the next thing he can do is reject any new drilling in the Arctic and in the Gulf,” Richardson said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.