Donald Trump Echoes Ross Perot’s Anti-Insider Rhetoric, Expands His White Male Base

Before there was Donald Trump, there was H. Ross Perot.

If pundits and political operatives appear both dumbstruck and shell-shocked by the rise of the New York casino mogul to presidential front-runner, it may be that they have short memories. After all, only a quarter-century before Trump blowtorched Jeb Bush into political oblivion, Perot helped bludgeon Bush’s father into early retirement — with a similar message and coalition. Both men appealed to voters eager for a champion from outside the Beltway. The key difference is that by running as a third-party general-election candidate, Perot left his mark on only one election. Trump’s primary campaign threatens to harness the old Perot constituency, brand it and use it to reshape an entire party for years to come.

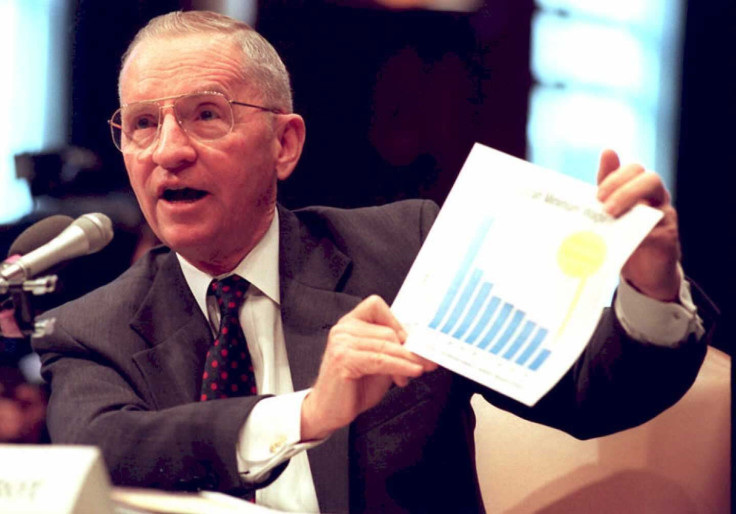

Trump has largely been depicted as an unprecedented phenomenon, and beyond their profiles as fast-talking moguls who built their own business empires, Trump and Perot are not obviously similar. The former is a tall, ostentatious New York reality TV show star with a penchant for inflammatory slogans that gloss over policy details. The latter was a diminutive Texas-twanged Warren Buffett, a buttoned-up, all-business wonk whose version of letting it fly was maybe adding a colorful metaphor or two to his long-winded descriptions of his low-tech (and ubiquitous) graphs. Among Perot's most memorable zingers came when he derided reporters for wanting him to "sound bite" his responses into "an easy, six-second answer, and America needs more than six-second answers.''

But appreciating why Trump has been successful — and how he may represent something more complicated than the typical Republican standard-bearer — is to understand the Perot-tinged roots of the political coalition that Trump has so far marshaled.

The two used their swashbuckling, anti-insider personas — and vast personal resources — to mount insurgencies at similar historical moments. Channeling a populist distrust of what has once again emerged as an epithet — the establishment — both Perot and Trump built their presidential bids around voters’ intensifying angst about globalization, corruption and America’s precarious economic standing. Their candidacies found resonance after painful economic slowdowns brought on by high-profile financial crises, and their biting critiques of politicians, corporations and crony capitalism attracted big audiences after twin eras of government bailouts.

Perot and Trump present their personal fortunes as both a firewall against the influence of special interests and as proof of the kind of business acumen they would bring to governance. Both suggest they’re uniquely positioned to clean house and save the country from economic turbulence and mismanaged government. Having built their own commercial empires, Trump and Perot also positioned themselves as independent critics of the corporate establishment, expressing contempt for high-paid executives who work their way up the traditional company ladder.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the threats of foreign economic competition, deindustrialization and domestic job losses were becoming a major political and cultural issue. And Perot’s criticism of the Bush-sculpted (and later Clinton-backed) North American Free Trade Agreement fueled his appeal among working-class voters threatened with economic dislocation.

Twenty four years later — after millions of U.S. manufacturing jobs moved overseas — Trump has appealed to those same fears, berating the Obama administration’s proposed Trans Pacific Partnership as a raw deal for American workers. Just as Perot would come to tout the idea of tariffs to protect the American economy, Trump has promised to support such trade barriers if he wins the White House. He was rewarded with an overwhelming win in South Carolina and solid support in the Deep South and Appalachia, where trade-related job losses have wreaked havoc on local economies.

The focus on international trade is part of the candidates’ stoking of some Americans’ fears of foreigners. Perot warned of the “giant sucking sound” of U.S. jobs moving south into Latin America. Trump has promised to build a wall to prevent immigrants from flooding north over the border and into the United States; exit polls show he won the most support in South Carolina among voters who said they want undocumented immigrants deported from the United States. Trump’s efforts to spotlight such fears no doubt gained traction from post-9/11 America’s focus with international terrorism and the recent attacks in Paris and San Bernardino.

Not surprisingly, Perot and Trump appeal to a similar voter base. Exit polls from 1992 primaries and the general election showed that Perot forged a base of disproportionately white, male and independent-leaning voters. Among Democrats, Perot seemed to appeal to more conservative blue-collar “Reagan Democrats.”

Likewise, polls during the 2016 campaign cycle have shown Trump doing well with more white, male and independent-leaning GOP voters. The New York Times recently reported that one of Trump’s strongest bases of support is voters who “are self-identified Republicans who nonetheless are registered as Democrats.”

Other demographic similarities abound. Exit polls, for instance, showed the income group most strongly supporting Perot’s campaign were those making between $30,000 and $50,000 a year, roughly the same income demographic that polls show have been enthusiastic about Trump.

“There are significant similarities in the support profile of Trump and Perot,” University of Virginia political scientist Larry Sabato wrote last year. He also saw overlap with 1992 Republican primary candidate Patrick Buchanan, writing: “ Unquestionably, elements of style link Trump, Perot and Buchanan: brashness, bluntness, and straight talk. All three men were more than willing to push hot-button issues that stirred many voters’ passions. In this respect, they were Barry Goldwater-esque, providing a choice, not an echo, to voters.”

Within the GOP, wrote National Journal’s James Barnes at the time, Perot won the support of voters who were dissatisfied with the Republican establishment and pessimistic about the economic direction of the country. That outlook is also reflected in the Trump coalition. A Rand Corporation survey found that the strongest predictor of support for Trump among Republicans is if they believe “people like me don't have any say about what the government does" -- 86 percent of GOP voters who say they agree with that statement say they support Trump.

Courting these disaffected voters, Perot and Trump engaged in high profile fights with Republican Party leaders: Perot accused them of dirty tricks, and Trump has complained they have not treated him fairly.

While there remains debate over whether Perot’s 19 million votes actually swung the 1992 general election to Bill Clinton, it’s clear that his criticism of the Republican establishment and party leader George H. W. Bush contributed to the incumbent’s troubles that year. But his campaign built no enduring institutions, limiting the impact of his two presidential runs.

Trump, though, is aiming to effectively take over the GOP, running a Perot-like independent insurgency within the party itself. If successful, that tactic could put him in a far more advantageous position than Perot ever achieved.

The two major parties have strong roots and infrastructure all over the country. In the past, independent candidates have run third-party campaigns, in part, to avoid trying to mount what they perceived to be unwinnable intra-party fights. But the Faustian bargain of such a strategy is being left to wage a nationwide general election campaign without any party machinery and thus a diminished chance to win. Trump instead saw a crowded GOP field with no singular ideological heir and a chasm between party elites and rank-and-file voters — and consequently an opportunity to acquire that machine for his own ends, potentially putting himself in a far more powerful position than a typical third-party candidate.

If successful, the implications of such a strategy could be far-reaching, because it enables Trump to put his mark on a national Republican machine that will exist well past the 2016 election.

A Trump-run Republican Party, for instance, could see a changing of its elite guard, whereby longtime power brokers and donors used to calling the shots are replaced by the billionaire’s handpicked apparatchicks. With Trump’s views defying the traditional policy prescriptions of GOP elites, the party could be forced to confront its previous orthodoxy on everything from Wall Street taxes to trade policy to its views of the Iraq War — and pre-emptive wars in general.

Some Republican operatives still believe they can stop that fearsome scenario by denying Trump the party’s nomination — and therefore access to its infrastructure — through a contested convention. But others say party elites no longer have the power to grind grassroots momentum to a halt.

“There is no mechanism,” former Utah Gov. Michael Leavitt, a Republican, recently told the New York Times. “There is no smoke-filled room. If there is, I’ve never seen it, nor do I know anyone who has. This is going to play out in the way that it will.”

If that proves true, the giant sucking sound could be the din of Trump pulling in GOP voters to his new brand of Republicanism.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.