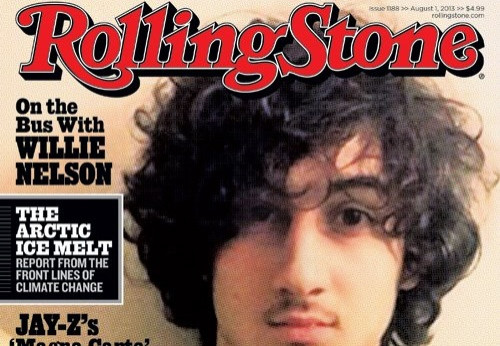

Rolling Stone Boston Bomber Cover: Was The Dzhokhar Tsarnaev Glamour Shot Unethical Or Just In Poor Taste?

The social media firestorm over Rolling Stone magazine’s Aug. 1 cover says far more about the intractability of Twitter-born outrage than it does about journalism ethics. But for media types who care about such things, it’s still worth asking if Jann Wenner’s storied music glossy has crossed an ethical line.

The cover, in case you missed it, features the Boston bombing suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, who has pleaded not guilty to 30 charges related to the bombing, including using a weapon of mass destruction to kill. The image prefaces an 11,000-word feature story on Tsarnaev’s transformation from nice guy to monster -- a story that hadn't even been posted online before the blowback began late Tuesday. Major drugstore chains, including Massachusetts-based CVS, have refused to sell the issue. On Twitter, outraged readers and even a few celebrities have been weighing in for the last day and a half. Donald Trump called for a boycott. The actor James Woods, a graduate of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, called the magazine a “s--t rag.”

Janet Reitman, the story’s author, complained via Twitter that people were sounding off on the cover before they had read the article, calling the prepublication backlash “astonishing.” But for those upset by the image, particularly people in the Boston area for whom the bombings hit home, the article was beside the point. It was the presentation by a rock ‘n’ roll magazine that seems to be glamorizing -- some would say fetishizing -- a terrorist. Bathed in soft light, Tsarnaev looks like a member of the Strokes. The photo appears to be a selfie Tsarnaev posted on social media but could just as easily be have taken by Annie Leibovitz.

It was a bold choice, to be sure, but was it unethical? The Society of Professional Journalists’ Code of Ethics, a set of guidelines voluntarily adopted by news professionals, includes a section on “Minimizing Harm.” Specifically, the code asks journalists to “show good taste and avoid pandering to lurid curiosity.” But those are highly subjective concepts, particularly in the kind of pop-culture journalism practiced by Rolling Stone.

Kevin Z. Smith, SPJ’s national ethics chairman, said readers should take into account that Rolling Stone frames its journalism differently than do general-interest newsweeklies such as Time or Newsweek -- which, it should be noted, have both featured controversial figures on their covers.

“When I first saw the cover, I thought two things,” he told International Business Times by email. “One, this seems to be keeping with Rolling Stone’s persona, and two, I’m old enough to remember Charles Manson being on the cover. So, this isn’t the first time they’ve tread on sacred ground. Wouldn’t you expect that sense of irreverence from a magazine born from rock and roll?”

At the same time, Smith said that, in terms of journalism ethics, intentions matter, even for Rolling Stone.

“If it chose this cover for shock value then that is wrong,” he said. “They have to also take into consideration the harm it would do in the presentation. It’s not sufficient to simply run the photo because you have it and the legal right.” (Though Rolling Stones doesn't appear to have licensed the photo.)

Katy Culver, associate director of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Journalism Ethics, agrees that Rolling Stone’s editorial should be viewed under a different lens than that of, say, the New York Times, which ran the same image of Tsarnaev. But she believes the magazine could have minimized the backlash by posting the image and the story simultaneously, thereby presenting the cover in the context of Reitman’s in-depth reporting, which wasn’t online until the following day.

“I think they made a mistake in releasing the cover on their social media and just a few hints on the piece, rather than releasing the piece as a whole,” she said. “They used a pretty standard approach to marketing an upcoming cover, and it blew up in their faces.”

The notion of putting a killer or suspected killer on a magazine cover is by no means new ground, nor is the idea of publishing images of notorious figures in certain contexts. Smith said it’s impossible to have the conversation without bringing up Time magazine, which in 1994 was accused of darkening a cover image of O.J. Simpson as a means of implying his guilt. Smith also pointed out that Rolling Stone itself is no stranger to this type of “visual editorializing,” as its 1970 star-like treatment of Charles Manson shows.

Culver, however, noted that the current media landscape is vastly different than it was four decades ago, and some news outlets, particularly print properties, haven't yet adapted to the idea of journalism as an ongoing conversation.

“When they ran the Charles Manson cover, they were a monologue,” Culver said. “They were one organization speaking out to many, many people. Those days are gone. They’re part of a new era in journalism. The audience, when they’re not happy, will speak back, and they’ll speak loudly.”

In the end, both Culver and Smith agree that Rolling Stone’s response to the controversy -- a one-paragraph statement defending its cover but offering scant insight into its decision-making -- fell short.

“The boilerplate comments don’t really help their cause,” Smith said. “Pulling back the curtain here and telling us how this came about is the transparency needed to create credibility.”

Got a news tip? Send me an email. Follow me on Twitter: @christopherzara

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.