The Uncounted

Since Hurricane Katrina, the New Orleans school system has been reborn. But somewhere along the way, an untold number of students may have been left behind.

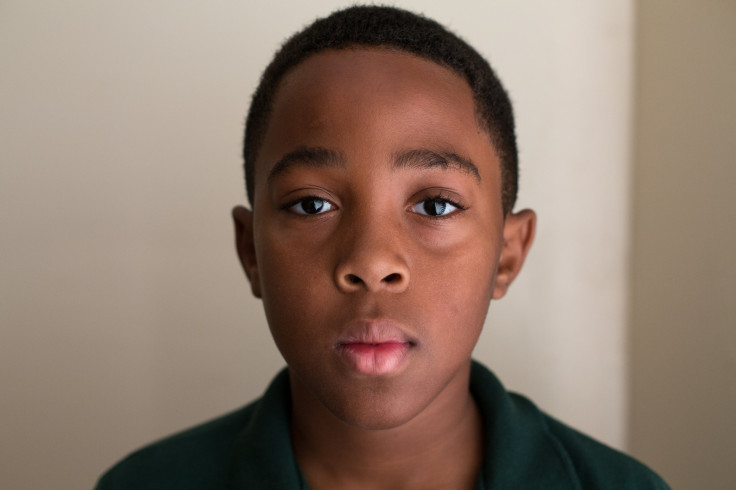

Donnis Osbey was nine months pregnant when Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans, forcing her and roughly a million others to flee the Gulf Coast. Her son Jeremiah was born 12 days later in Houston. When they returned in 2008, Osbey hoped the education reforms following in the wake of Katrina boded well for her son. Now, that hope is gone.

“I should have stayed in Houston,” Osbey sighs.

Jeremiah just started at his sixth school in six years. The fifth-grader, who has ADHD and autism, has struggled to fit in at New Orleans’ charter schools, which now educate more than 90 percent of the city’s public school children. Things reached a head at the charter Jeremiah attended last year, Osbey says. Upon hearing the school’s name, Jeremiah’s ever-present smile fades, and his hands shoot up to muffle his ears. “I used to cry every day when I came home,” he recalls.

“People ask me if things are better 10 years after Katrina. I say, 'Better for whom?'”

Just shy of 10 and full of restless curiosity, Jeremiah periodically springs out of his seat, soliciting patient correctives from his mother. Osbey, a substitute teacher, says the school failed to provide services adequate for Jeremiah’s needs. He often ended up in the “Reflection Room,” where disruptive students were housed. Jeremiah spent an average of two hours a day there last February, says Julia Wilson, a Tulane University law student who advocates for public school families. (By law, schools cannot punish students for behaviors related to their disabilities.)

As difficult as post-Katrina schooling has been for Jeremiah, it was hardly any easier for his mother. Class removals gave way to suspensions. “I was getting calls every day,” Osbey says. “I wasn’t able to work.”

As schools took on new management and families were compelled to choose between them, Osbey found herself navigating a bewildering terrain. Some schools promised to meet Jeremiah’s needs, Osbey says, only to recommend later that he leave. Others admitted up front that they couldn’t help him.

“That wears down on a parent,” Osbey says. “It’s been a journey.”

A decade after Hurricane Katrina spurred New Orleans to undertake a historic school reform experiment -- a shift to a virtually all-charter district with unfettered parent choice -- evidence of broader progress is shot through with signs that the district’s most vulnerable students were rebuffed, expelled, pushed out or lost altogether.

Broader measures show a rejuvenated school system. ACT scores in the state-run district increased from 14.5 in 2007 to 16.4 in 2014, and far fewer students in the majority-black district attend schools deemed failing. The proportion of Orleans Parish high school graduates enrolling in college has grown more than 20 percent since 2004.

But parents of children like Jeremiah feel left out. Critics worry that many children, particularly those with behavioral needs, fell through the cracks. And newly available data from independent researchers, corroborated by former district employees, suggest that due to misreporting, official graduation rates may be overstated by several percentage points.

In relinquishing oversight to independent charter operators, former employees say, district authorities lost sight of at-risk students. Under stiff pressure to improve numbers or face closure, schools culled students and depressed dropout rates. And as families muddled through a complex and decentralized system, a sizable contingent of at-risk students may have left the system unrecorded.

“With an open system like that, it’s relatively easy to misreport information and fudge it,” says Clinton Baldwin, who coordinated the district’s student data from 2012 to 2014. “It was definitely something that was prevalent.”

Meanwhile, for the parents of the most difficult-to-teach students, the notion of school choice seemed to become a mirage.

“It’s not what you decide,” Osbey says. “It’s what they decide for you.”

In The Wake Of Katrina

Few in New Orleans now argue for a return to the old days. Corruption was so rampant that the FBI had a desk at the local school board. As in many high-poverty districts, achievement rates were abysmal. In 2003, a school valedictorian infamously failed her high school exit exam. She passed on the seventh try.

“It’s hard to articulate if you weren’t here just how inequitable it was,” says Michael Stone, co-CEO of the nonprofit New Schools for New Orleans.

That state of affairs, along with the rest of the city, was upended on Aug. 29, 2005.

All but 16 of the district’s 128 facilities were damaged when the levees failed. In the Lower Ninth Ward, where floodwaters flattened homes and left cars perched in trees, teachers recall returning to the beloved Dr. Martin Luther King Elementary to find messages scrawled on the blackboards of the second floor -- the writings of survivors who sought refuge there.

But despite the devastation it wrought, Katrina created a unique opportunity for those intent on remaking the educational system.

“There was some progress before Katrina,” says Adam Hawf, a former assistant superintendent of the state department of education. “But the hurricane accelerated the shift.”

Katrina created a “political vacuum for a few powerful leaders to step in,” says Doug Harris, director of the Education Research Alliance at Tulane. “It wasn’t really a community decision.”

Within weeks, the district had laid off more than 7,000 school employees, positions filled largely by energetic and mostly white newcomers from Teach for America and similar programs. By 2010, the proportion of African-American teachers had dropped from over 70 percent to roughly half.

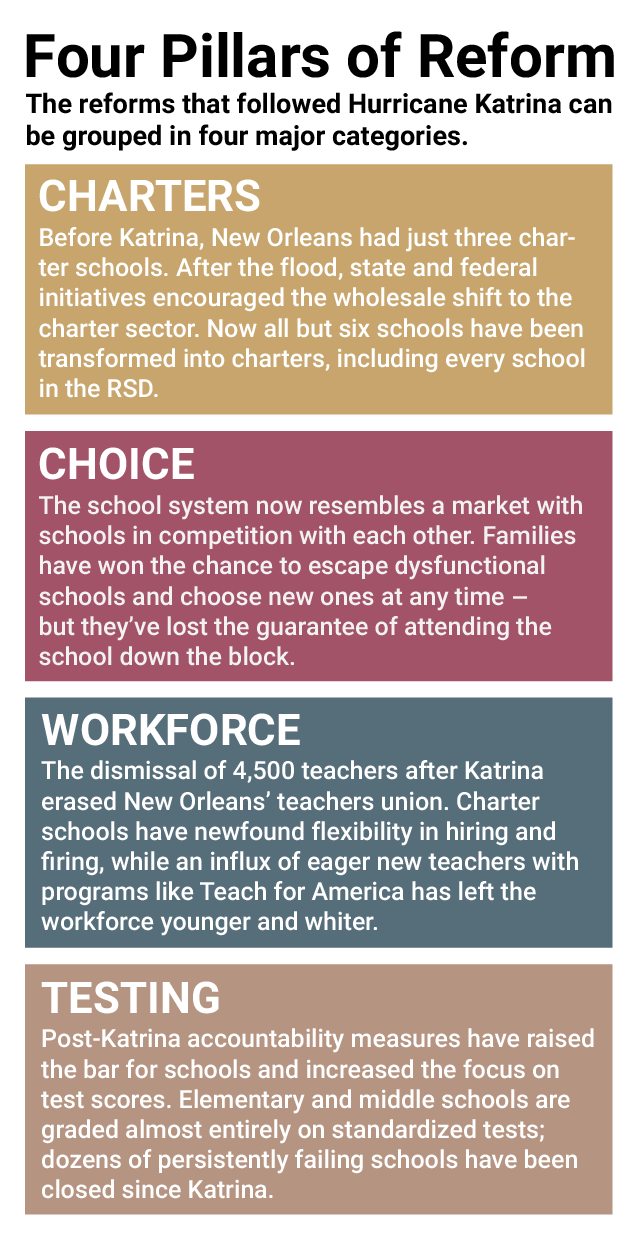

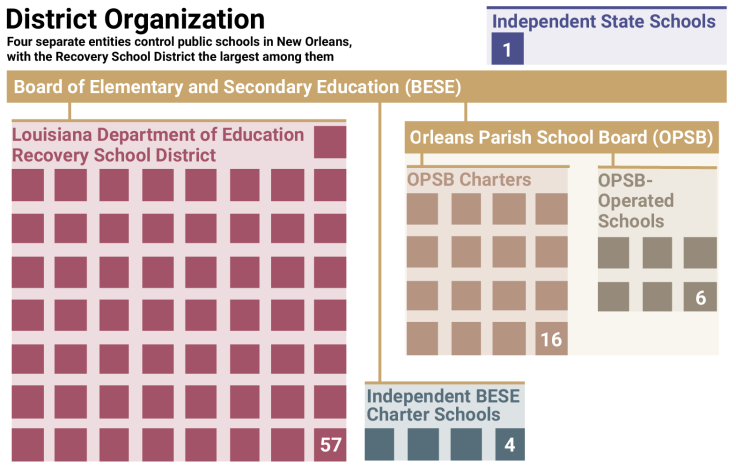

In November 2005, lawmakers empowered the state’s existing Recovery School District to take over schools performing below the state average. In all, 107 schools previously run by the Orleans Parish School Board were wrested free, to be turned over to charter operators. Today the RSD is the nation’s only district composed solely of charter schools, which receive public funds but are exempt from some regulations around staffing and discipline.

The pace of reforms, so soon after the flood, rattled some community members. Schools deemed failing were closed -- their staff fired and their students dispersed -- then reopened as charter schools. Millions of dollars flowed in to spiff up the new charter schools, which often had longer days, stricter discipline and steeper expectations of students.

But as families trickled back -- an enrollment of nearly 65,000 students in 2004 had plummeted to 26,000 in 2006 -- glimmers of hope appeared. By 2010, schools had become less chaotic and test scores were rising. Opinions vary widely, but many students saw improvements in everything from teacher quality to lunch options.

“Before Katrina I did not like school,” says Ke’Ante Robinson, 18. “After Katrina, the school system really did upgrade.”

'Better For Whom?'

But cracks in the system soon emerged. Returning students, many of whom were grappling with trauma, encountered tumult as schools repeatedly changed hands.

Facing post-Katrina instability and stringent discipline in the upstart charter schools, students shuffled around the district with alarming frequency. Suspension and expulsion rates climbed. By 2012, a few schools saw suspension rates topping 60 percent. The city as a whole logged more than 46,000 out-of-school suspensions in 2013 -- upwards of one per student.

Karran Harper Royal, a special education advocate and prominent parent leader, says the reforms shortchanged children with disabilities. “People ask me if things are better 10 years after Katrina. I say, 'better for whom?'”

Many new charter schools lacked the staff and experience to meet special education regulations, says Eden Heilman, an attorney with the Southern Poverty Law Center. “Kids would either be denied on the front end or they would go to the school and the school just wouldn’t provide services.”

Crystal Walker, a mental health counselor and mother of three children with special needs, knows that struggle well. She has been locked in a battle with charter school Akili Academy over what she claims is the school’s failure to meet her children's needs.

James, age 7, struggles behaviorally. Last year he was suspended for a laundry list of offenses, from running in the halls to throwing chairs. In six months of 2014, James was removed from his first-grade class on 85 out of 92 instructional days, including 30 out-of-school suspensions and a visit from the police.

“The solution was always suspension,” Walker says. Instead of finding a new path for James, Akili staff pushed to expel him, says his mother. Though the school eventually identified James with a disability -- emotional disturbance -- he is attending a different school this year while still technically an Akili student.

Walker lodged legal complaints with the state education department, but she has fought to keep her middle son at Akili. “It will just get worse at another school.”

Akili principal Allison Lowe says that in "extreme cases" the school will send challenging students elsewhere. "It's a very rare situation for us to say that it might not be the best placement at Akili," she says. "Until then, we are going to create the best environment at our school."

In the last two years, Akili has added two positions for staff to oversee behavioral interventions. In response to criticism, a group of six Akili parents wrote a letter in 2014 praising the school's special education services.

But Walker's experience isn't unique. In 2010, the Southern Poverty Law Center filed a class-action lawsuit over the state’s issues identifying and serving students with special needs. Since settling in 2014, the district has implemented sweeping changes. Earlier this year, the RSD closed a charter school for special education violations.

“The lawsuit is actually helping to make sure that people aren’t pushing out students,” says Patrick Dobard, superintendent of the RSD.

But with an accountability system that will close schools for subpar scores, principals still face pressure to manage student enrollments. In a recent study, nearly a third of the principals interviewed admitted to using marketing and selection tactics to reel in the best students and keep troublesome ones out.

"I have seen students getting kicked out,” says Ron Gubitz, principal of Renew Cultural Arts Academy, a charter school. “The enrollment game is the game in town. It’s how we get our funding.”

“Each individual school is doing what it needs to survive,” says Huriya Jabbar, the University of Texas education researcher who authored the study. “There’s a lot of concern that there are students who just aren’t accounted for in the system.”

Exit Code 10

If students were falling off the rolls, though, one would expect to see it in graduation data. Some, like former assistant superintendent Hawf, find it implausible that students disappeared. “We have fewer falling through the cracks now than before Katrina,” he says.

Official graduation rates in the RSD surged from just under 50 percent for the class of 2009 to 68 percent in 2012, before receding back to around 60 percent in 2014.

But activists weren’t the only ones raising alarms over students getting lost in the shuffle. By 2010, RSD data administrator Clinton Baldwin was privately growing suspicious of dropout data.

A New Orleans public school graduate from a “rough neighborhood,” Baldwin says he joined the RSD in 2009 to bring a local voice to data-driven conversations often dominated by white newcomers. “I wanted to be the person that kept the charters connected to the community,” Baldwin says.

Peering into enrollments over time, he made a disturbing discovery: Schools seemed to be hiding their true dropout figures.

Each student who leaves a Louisiana public school receives a so-called exit code. Some are dropouts. Others, labeled “legitimate leavers,” don’t count against graduation rates. The state could verify most legitimate leavers, like children who move a town over. But it couldn’t check transfers out of Louisiana. There arose a perverse incentive to designate students who disappeared with Exit Code 10: Transferred Out of State.

“It was well-known within the data circles,” Baldwin says.

Other data managers in the RSD recall how missing students received Exit Code 10. “If they said that the child went out of state, it was an easy way out,” says Dena Robateau, who worked at the RSD from 2007 to 2010. “That was the easiest thing to do.”

“I’m not a bleeding heart, but I’d like to know what has happened to these kids?”

Christina Long, who was a data manager from 2007 to 2011, says the problem was acute at charter schools. Auditors had direct access to publicly run schools, but charter data were self-reported. “We had no way of knowing their enrollment counts,” says Long, who labels the data from charters as “tainted.”

Former assistant principal Shawon Bernard says it came down to self-preservation: Low performance scores could get a school shuttered. “Part of your grade is based on your dropout rate, so you need to make sure those numbers are good numbers,” says Bernard, who stewarded data at her school.

Exit Code 10, Bernard says, provided cover. “Those were the children who disappeared.”

Baldwin’s analysis confirmed the data managers' concerns. He promptly alerted his superiors. “I was one of the people shouting from the rooftops,” Baldwin recalls. “It was a disservice for our population to have charter schools come in, collect money in October, then discard the student for the remainder of the year.”

Baldwin is reluctant to cry foul on particular schools, saying the practice wasn’t universal. But he demanded in private that the state take up the issue. (In an email, RSD deputy chief of staff Laura Hawkins told International Business Times, "No one from this administration was here in 2010 so we can’t know whether or not that happened.")

The state Education Department also declined to comment on the specific allegations, characterizing inconsistent exit codes as a statewide issue. "The Louisiana Department of Education manages enrollment, not individual schools," the department said in a statement to IBTimes.

The Education Department issued new guidance for exit codes in 2013, reinstituting audits that had been abandoned in 2008.

The issue was still evident for the class of 2013. For that group, the state audited a random sampling of exit codes throughout Louisiana. In the RSD’s New Orleans schools, all 14 records plucked for review lacked verification -- a failure rate of 100 percent, the highest of any district.

'What Has Happened To These Kids?'

Recently, researchers outside of the district have -- for the first time -- peered into the RSD’s post-Katrina graduation data.

The analysis comes from a small volunteer outfit called Research on Reforms, which formed after Katrina and soon grew critical of the changes. Eventually, the state began refusing its data requests. It took a multiyear lawsuit ending in late 2014 for the outfit to acquire state enrollment records. The group's report on student exits, published earlier this month, appears to vindicate Baldwin’s concerns.

Among freshmen entering RSD high schools in 2006, 8 percent were marked as out-of-state transfers over four years, the report says. For students who entered two years later, that proportion nearly doubled. More than 15 percent of students were marked as moving to different states.

For comparison, in the Orleans Parish district -- which includes selective schools with higher socioeconomic profiles and lower mobility rates -- Exit Code 10 held steady at around 5 percent.

Absent a complete audit, it’s impossible to know exactly how many of the students who left high schools between 2006 and 2012 were legitimate out-of-state transfers and how many had actually dropped out. But the numbers are significant. If half of the Code 10 exits in 2011-2012 were truly dropouts, RSD graduation numbers would be depressed by roughly 7 percent.

“I’m not a bleeding heart, but I’d like to know what has happened to these kids?” says Charles Hatfield, the retired district administrator who analyzed the data.

Ken Pastorick, a communications officer at the Louisiana Department of Education, told IBTimes that claims of students falling through the cracks are "tired lies that are repeatedly proven to have no basis in fact." The department did not comment on the exit code data in the report.

Doug Harris, the Tulane professor, says the report raises an “important potential issue,” but notes that it falls short of direct proof. “It's hard to say whether these numbers are alarming or not, but the data collection process is a legitimate concern,” he wrote in an email.

On the other hand, Harris says, the report might overlook another problem: “Some students may get 'lost' even before high school, numbers that wouldn't be audited at all.”

Reformers Reformed

The RSD, facing community pressure, has made substantial efforts to ensure students don’t get pushed out. A new enrollment system allows families to list their top eight picks. A lottery-like algorithm matches kids to schools so no one is excluded.

And a centralized expulsion system, designed in consultation with community groups, has curbed schools’ abilities to dump students for minor misbehavior, such as talking back to a teacher or violating dress codes. The state reports that expulsions dropped 39 percent last year.

“We listened to the community,” says Superintendent Dobard. “Parents have more opportunities now that the district is decentralized to make their voices and concerns heard.”

The efforts of people like Clinton Baldwin and Karran Harper Royal, the special education advocate, reflect a less-recognized current of reform that has characterized the post-Katrina recovery. Though outsiders largely defined the course of institutional reforms, native New Orleanians have made them more equitable.

“Many of the local critics of this system have led to dramatic changes,” says Stone, the head of the reform outfit New Schools for New Orleans.

That’s true in the charter community as well. “I've seen a big shift in the last five years,” says Gubitz, the principal at the K-8 Renew Cultural Arts Academy. “We are all listening more.”

At Renew, every student takes classes in music and art -- not a given in New Orleans charters. The school boasts both a marching band and a flag squad. Alex Reed, a New Orleans native and pre-kindergarten teacher who worked at the school before Renew took over in 2010, marvels at the transformation. “There used to be brawls twice a week,” he recalls as his students experiment with Play-Doh. “The whole culture of the school has changed.”

Gubitz and his staff have strived to create a humane environment. Unlike more disciplinarian charter schools, Renew doesn’t enforce total silence in hallways. In the morning, students belt out the school song, a poppy number accompanied by Gubitz on acoustic guitar. Suspension is only a last resort.

But many students never had a safety net. A hint as to the size of that population is the number people aged 16-24 who are neither working nor in school. Estimates of their ranks swelled from roughly 16,000 in 2011 to 26,000 in 2013.

After Katrina, programs to reach this population also expanded. The Youth Empowerment Project (YEP), for example, grew from a single classroom in 2006 to an alternative education program reaching more than a thousand young adults a year through GED classes and work training.

On a bright day earlier this month, a group of teenagers laugh as they fix bicycles in YEP’s retail bike shop, part of the employment skills program. Upstairs, staff members discuss their game plan for the coming year.

Staffer Darren Aldridge, who was 14 when Katrina struck, bounced through five high schools before dropping out and getting his GED through YEP. He now runs a YEP program that helps students pass high school equivalency tests.

Aldridge is ambivalent about the progress since Katrina. “When you see these 16, 17-year-old kids coming to get a GED, what does it mean?”

To Aldridge, the answer is clear. “They pushed a lot of kids out of the system.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.