Missing Meles Zenawi: Ethiopia’s Power Vacuum Threatens Western Interests In Africa

ANALYSIS

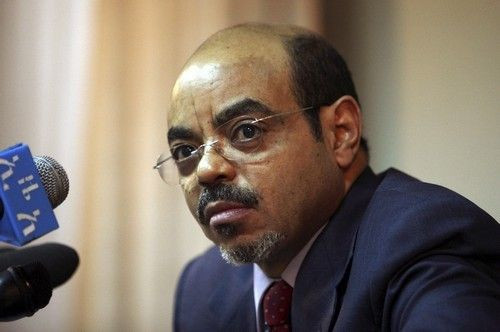

Meles Zenawi, prime minister of the East African nation of Ethiopia, passed away Monday night at a hospital in Brussels. The 57-year-old died of a "sudden infection" preceded by months of illness, according to the BBC.

Meles had been the dominant political figure in Ethiopia since his forces overthrew the communist Mengistu regime in 1991. As the head of Ethiopia's preeminent political party, the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front, he was elected as prime minister for the first time in 1995.

Meles went on to win the next three general elections, holding onto power despite accusations of increasing authoritarianism over the years.

Under Meles, Ethiopia was a reliable ally to the West in East Africa. Now, that may change.

One of the deceased prime minister's most exceptional skills was to steer political dialogue in a way that benefited both the EPRDF and the West.

Richard Dowden, director of the Royal African Society, told the Guardian that Meles was "the cleverest and most engaging prime minister in Africa -- at least when he talks to visiting outsiders."

"I found him funny, charming and self-deprecating," he added. "But then someone told me that, when addressing Ethiopians, he's dogmatic, severe and dictatorial."

It is this dichotomy that made Meles such a pivotal -- and controversial -- figure. His passing has great implications not only for Ethiopia, but for Western diplomacy across the African continent.

Warrior for the West

Meles, with his wire-frame glasses and trim goatee, had the quiet demeanor of an academic. He held two masters' degrees in business and economics, one from Open University in the United Kingdom, and another from Erasmus University in the Netherlands. He was soft-spoken and always sharply dressed in Western attire -- it is hard to find photos of him in anything other than a well-tailored suit and tie.

According to some reports, he rarely smiled.

Meles was a staunch ally of the West -- and of the United States especially. Under his leadership, Ethiopia partnered with the U.S. military and CIA to combat militants linked to al Qaeda in neighboring Somalia . The U.S. Department of State reports that Ethiopian "defense forces have participated in U.S.-sponsored training and engagement, including peacekeeping operations, professional military education, management, and counterterrorism operations."

With U.S. assistance, Ethiopia has become one of Africa's most active nations in terms of peacekeeping and international military assistance. For years, its military initiatives have been aligned with U.S. interests in the region.

A remote airport in the southern forested regions of Ethiopia has even become home to a small fleet of U.S. drones. Last year the White House confirmed the presence and operations of these drones, but claimed they were for surveillance purposes only.

Armed or not, these drones became a useful tool in the fight against al-Shabaab, a Somalia-based terrorist group that threatens to destabilize the Horn of Africa.

Ethiopia's Western alliance goes far beyond military cooperation. Under Meles, Ethiopia abandoned the Soviet ties it had forged under its former communist government and opened up to Western assistance that continues to this day.

In 2012, the United States is slated to spend more than $580 million on Ethiopian development. The World Bank has planned to lend about $520 million for various initiatives including electoral system assistance and women's development, and the United Nations has also pledged millions of dollars for various programs from ameliorating hunger to combating AIDS/HIV.

An Uphill Climb

This assistance has helped to spur Ethiopia's impressive economic growth over the last decade. The government under Meles was a resounding success when it came to fiscal matters; the EPRDF administration implemented effective development programs and kept corruption to a minimum.

Ethiopia saw its average real GDP grow by 11 percent over the last six years consecutively, even amid the global recession. And much of this revenue has been put to good use, according to a 2012 World Bank report.

"Over the past two decades, there has been significant progress in key human development indicators," said the report.

"Primary school enrollments have quadrupled, child mortality has been cut in half, and the number of people with access to clean water has more than doubled. More recently, poverty reduction has accelerated."

Meles was a driving force behind these accomplishments. He often played down the role of foreign assistance in Ethiopia's development -- a justifiable stance, since international aid amounts to little in the hands of an inept or corrupt government. Foreign funds may have fueled progress, but Meles was the man at the helm. And it was his relatively transparent use of those funds that continued to attract investment over the years.

"We have taken full charge of our destiny, devised our own strategy, and maximized the mobilization of our domestic resources to achieve the [development goals]," he said during a 2010 speech.

"We made the best use of the limited available international assistance to supplement our own efforts."

Progress notwithstanding, Ethiopia still faces monumental challenges. Inflation and a high cost of living due to the global recession have not helped the nation's poor -- nearly a third of the population is under the poverty line. Climate change and recurring droughts threaten the food supply, not to mention the livelihoods of agricultural workers who make up 85 percent of Ethiopia's workforce. Malaria and AIDS remain serious threats, despite successful government initiatives to improve the country's health care infrastructure.

But the fact remains that the country has been headed in a positive direction for the past decade, and Meles can be credited with the liberalization and stabilization of one of Africa's most vulnerable economies.

Wrong on Rights

On the other hand, it's easier to steer a nation efficiently when you have an iron grip on power.

For all their economic successes, Meles and the EPRDF have a poor record for human rights, and this has affected the legitimacy of the national government. Ethiopia was meant to be a multi-party democracy, but over the past several years it has effectively become a one-party state where opposition groups have little chance of shaking the status quo.

Meles first became prime minister in the general elections of 1995. He and his party emerged victorious once again in 2000, and again in 2005, and once more in 2010. But with each passing term, the voices of dissent grew louder and louder. Opponents contend that Ethiopia's political process effectively bars other parties from having a fair chance at success.

Things turned violent following the 2005 elections, when mobs of protesters took to the streets in the months following the May vote, which they claimed was rigged.

The EPRDF government clamped down hard, using excessive force that many observers called a "massacre." Security forces originally said that only 58 people had died, but it was later leaked that at least 193 had lost their lives -- many of them minors.

Another 763 people were wounded, and 20,000 were arrested during the protests, according to the BBC.

Meles has never admitted to his party's use of intimidation, violence or other illegal tactics against political opponents.

Recent years have also seen restrictions on free speech. A 2009 anti-terrorism law gave the government broad powers; it has since placed severe limits on free speech and the press. Several journalists have been sentenced to jail terms for "participation in a terrorist organization," according to the New York Times, as have hundreds of opposition supporters.

There have also been government-sponsored suppressions of rebellious groups, including Somalia-linked dissenters in the eastern region of Ogaden, the Anuak ethnic group near the border with South Sudan, and the Afar people close to the border with Eritrea, a country that has had a tense relationship with Ethiopia since it seceded in 1993. Border wars between the two countries have cost more than 70,000 lives since 1998, according to Al Jazeera.

Into the Abyss

These facts cast a long shadow over the legacy of Meles Zenawi. Now that he has passed away, a dangerous power vacuum looms. Can any successor to Meles exhibit the strength to keep up Ethiopia's economic growth while disavowing the government's brutal suppression of dissent?

As a matter of protocol, the baton has been passed -- at least temporarily -- to Deputy Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn. He will be acting prime minister at least until an EPRDF meeting in September, according to the Associated Press, and could hang onto the post until regularly scheduled elections take place in 2015.

Hailemariam has moved up quickly in government ranks over the past few years, but is not a central figure in Ethiopian politics. There is a chance he will become Ethiopia's next long-term leader, but it is also quite possible that power struggles will quickly unseat him.

"I believe he will face a great challenge of being taken seriously by his subordinates for three reasons," said Jawar Mohammed, an Ethiopia scholar at Columbia University, to AP. "First, as he never exercised real power at national level, there is little established fear and respect about him. Second, most of his subordinates are going to be individuals with longer experience and personal stature than him, which means they will overshadow him."

Many African politicians, like Kenyan Prime Minister Raila Odinga, are worried that Ethiopia will descend into instability without Meles at the helm.

"One fears for the stability of Ethiopia upon his death, because you know that the Ethiopian state is fairly fragile and there is a lot of ethnic violence," Odinga said, according to the Guardian. "I don't know that [Ethiopian politicians] are sufficiently prepared for a succession: this is my fear - that there may be a falling out within the ruling movement."

Meanwhile, the al-Shabaab militants who have been the target of Ethiopian military for years celebrated the passing of Meles.

"We are very glad about Meles's death. Ethiopia is sure to collapse," said spokesman Sheikh Ali Mohamud Rage to Reuters.

Ripe for Realignment?

The potential for unrest has broader implications throughout the global community. Now, Ethiopia's international backers may have to face the fact that the government they supported for decades has created a potentially volatile situation in East Africa.

Suppliers of financial and military assistance -- the United States first and foremost -- have turned a blind eye to Ethiopia's human rights abuses for years. Economic development has been encouraging, but the increasing authoritarianism of the EPRDF was no secret.

Ultimately, this support could come at a price. If the absence of strongman Meles results in instability, revolts or even an eventual overthrow of the one-party government, the United States could lose its most valuable African ally.

It's a scenario we've seen plenty of times before, as when the U.S.-backed Shah of Iran was overthrown in 1979, or just last year when the U.S.-backed presidents of Egypt and Tunisia were ousted.

Ethiopia could be a similar case.

Meles was a complex figure: a competent steward of the Ethiopian economy with little tolerance for dissent. Evidently, this was the sort of strongman Western powers wanted on their side. Now that he is gone, the inherent risks of supporting a human rights offender are becoming painfully clear.

For the first time in two decades, the future of Ethiopia hangs in the balance -- and with it, the fate of Western interests in and around the Horn of Africa.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.