NBA News: The Data Behind The 'Sophomore Slump,' If It Exists At All

Imagine an NBA team drafts a young prospect. Expectations are high for his first season, and for the most part, he lives up to the hype.

Perhaps he finishes in the top three of the Rookie of the Year vote, and moves into the offseason on the heels of a successful debut campaign. After time to digest his first year, a writer, or a coach, or a pundit, or “league sources” project this young star to have a dip in production. Rationalizations for the expected drop-off start flying: defenses will figure him out, his body will break down, he’s not mentally tough enough to adjust, he can’t keep up with the NBA lifestyle, and so forth.

A dreaded phrase gets thrown around—the player is due for a “sophomore slump.” The term describes a commonly held belief that, oftentimes, a good first-year player will regress in his second season, for any of that bevy of reasons. The idea, however, is largely based off anecdotal evidence. If a young player is perceived to be struggling, a sustained slump is an easy conclusion to draw, especially if a player has a bad game, week, or even month—as NBA players often do.

But what does the data show? What is the hard evidence for or against the general trend of a sophomore slump? Do most good rookies slump in their second year or do they improve?

The data suggests that the sophomore slump, as an over-arching trend, does not exist.

This conclusion was drawn by studying the win-share value, according to basketball-reference.com, of players who received at least one Rookie of the Year vote dating back to the 1983-1984 NBA season. Players who received ROY consideration qualified for the data because a player cannot “slump” if they were never good to begin with. The win-shares statistic is an estimate of how many wins a player contributed to his team over the course of a season, and while it is imperfect, like most statistics, win shares is a good measure of overall performance.

The total win-share value of each player’s rookie season was collected and then compared with the corresponding sophomore season’s value. Win-shares-per-game (or an average) was not used because the data needed to reflect games played to account for injuries.

So, simply put—each player’s rookie season performance was compared with the corresponding sophomore season performance to see if there was a “slump.” The result: of the 141 qualifying players, 91 improved their second season while 50 regressed. The sophomore class as a whole accounted for 747 wins, while the freshman class accounted for just 618.5.

On average, a team could expect a star rookie to garner an impressive 33 percent more wins their sophomore season compared with their rookie year. By every measure, the trend was that second-year players were worth more wins than they were in year one.

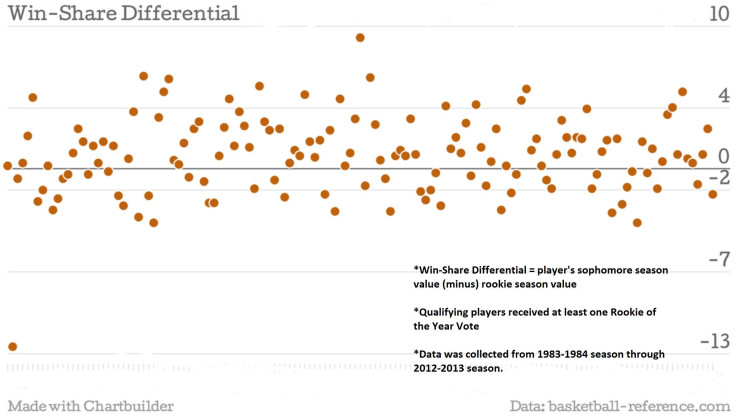

Below is a scatter plot marking the win-share differential (sophomore year value minus rookie year value) of each the 141 qualifying players from 1983 to 2013. The differential value indicates by how many win shares a player improved or regressed. If you were to connect the dots on the graph, it ends up looking like a seismograph reading, which goes to the show the relative randomness with which slumps come or go.

But an important thing to notice is that the majority of the graph is plotted on the positive side of the x-axis. Most players improved. (Here's a link to very basic data, to see specific players win-share values)

For further proof of the randomness of slumps, however, consider the fact that the largest drop-off from year one to year two belonged to Michael Jordan. He got hurt year two and was worth just 1.5 wins after being worth 14 wins in his rookie season. The steepest positive change belongs to LeBron James who improved by 9.2 wins. So an improvement or regression doesn’t necessarily project a career.

As another interesting aside, Adam Morrison actually improved his win-share value his second season by not playing in a single game because of an ACL injury. He went from being worth -1.5 win shares to zero. The graph show the year-to-year change in the 141 players and it’s interesting to see how quickly some young stars ascended or descended.

Projecting any given player’s second season is still a difficult task. Even the extremely small sample of Morrison, Jordan and James hints at that fact. But the data shows that as a whole, rookies might actually struggle more than sophomores.

“The rookie wall,’ I think, is really an issue,” Minnesota Timberwolves and 2015 Rising Star Game participant Shabazz Muhammad told International Business Times on Saturday. “I don’t think I really got that ‘sophomore wall’ yet. Hopefully, I don’t get it.”

Again the data backs up Muhammad’s theory. Rookies were worth 4.39 wins on average, while sophomores were worth 5.29 wins on average. Why might that be?

One reason might be a growth in maturity and a better understanding of an NBA lifestyle in a player’s sophomore season. Sophomores also have experience dealing with the heavy travel schedule and might have turned a corner physically to deal with the stresses of playing so much basketball.

“The games a grind and it’s not a two-hour workday,” Mike Procopio, Dallas Mavericks player development coach and former personal coach to Kobe Bryant, told IB Times. “It’s going to be a five-six, six-and-a-half hour workday, minimum.”

There is a certain amount of growth that needs to happen for young players to become comfortable with the lifestyle.

“Getting their NBA routine down, their daily routine, that takes time,” Procopio said. “To me it’s going to take you at least 18 months to stabilize for most players.”

Eighteen months would put a player comfortably into their second season. Stabilizing physically would allow a player to have more games played with top-level energy.

That isn’t to say that slumps don’t exist or that players don’t sometimes regress in their second year. Again, 50 of the 141 qualifying players in the data set regressed. But perhaps even higher expectations for sophomores who impressed in year one makes observers perceive a slump, even if the player is improving. Procopio, however, has his theories on the types of players who might be more inclined to actually slump.

“It’s probably going to be more, sort of the less skilled, active player that plays in the fullcourt, plays in transition,” he said.

“I think players that are just sort of, those pogo sticks [who] go 94-feet on the floor, make great plays in transition, those guys once you slow the game down, they’ll be a little more successful.”

Slowing the game down mentally takes time and more skilled players can fall back on doing small things correctly to counteract mental breakdowns. In other words, in year one “energy guys” might find success, but in year two the player might need more to their game. Skilled, more polished players shouldn’t have that problem. In theory, they would likely improve on those strengths. The idea is that a player who is less skilled, or perhaps has a lower basketball IQ, will be “found out” quicker.

Some big jumps upward in win shares from rookie year to sophomore season did, in fact, come from very skilled players.

Portland Trail Blazers big man LaMarcus Aldridge, who has a prolific post game, improved his win shares by 83 percent (3.4 to 6.2). Stephen Curry, winner of the 2015 3-point shooting contest, improved by 1.9 win shares or about 40 percent. James, who had the biggest jump in win shares, is known for his genius-level ability to see the floor and his high basketball IQ.

A player with a high IQ would find it easier to add to his game. While a simple idea, that’s the best way to counteract any loss in production because of opponents’ adjustments, according to Procopio. A sophomore-season-player might have fewer opportunities to make plays because of increased defensive attention and will have to do more with the decreased chances.

“We have to development other parts of their game, especially without the ball in their hands,” Procopio said, “the rebounding, the passing, penetrating into the lane, creating a problem without dominating the ball.”

The data shows that these little additions to a player’s game mean a lot and that most good rookies figure out how to improve their game in year two.

If nothing else, NBA teams have to back their young players up. A watchful eye will help ensure a team’s solid rookie will follow the overall trend of sophomore-season improvement. Ultimately, slumps are hard to predict and young players need to be coaxed into a successful NBA careers.

“If you just leave rookies alone and you don’t talk to them,” Procopio said. “That’s like playing Russian roulette.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.