Sputnik’s 55th Anniversary: A Milestone That Led to Curiosity And iPhone 5

Nobody alive on Oct. 4, 1957, will ever forget it: Russia, then the Soviet Union, launched Sputnik 1, the first successful earth-orbiting satellite. Americans who heard its tiny beeps on the radio and TV panicked because it proved the U.S. was technically behind what then was known as the U.S.S.R.

The world was different then: The U.S. and U.S.S.R. seemed as if they were eternal opponents in the Cold War. Almost daily, both nuclear powers were testing bigger and better atomic weapons in the atmosphere. Both were building bigger and better fleets of jets, missiles and submarines capable of blowing the other side to smithereens.

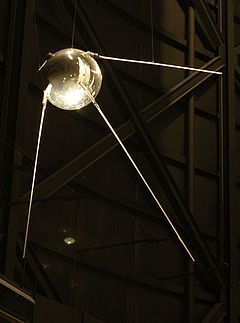

To be sure, the Soviets used an ICBM to launch the tiny, golden Sputnik into orbit. The satellite itself weighed only 184.3 pounds, was the size of a beach ball and orbited the earth every 98 minutes.

While the ostensible mission of Sputnik (Russian for “something that is traveling with a traveler”) was scientific as part of the 1957 International Geophysical Year, the America of President Dwight D. Eisenhower flipped out. Not only had the U.S.S.R. of the crude and boorish Prime Minister Nikita S. Khrushchev won the prize of being first in space, it proved it was tops in aerospace technology.

The national mood also fostered concern that if the Soviets could orbit a satellite so easily, what else could they do? Was America equipped to meet the challenge on the military side, too?

Within weeks, the Soviets were sending up dogs into space. Remember Laika, Belka and Strelka?

The Eisenhower administration reacted immediately. First, it reminded citizens that it, too, planned to launch the Vanguard satellite for International Geophysical Year. But the proposed Vanguard was a puny 3.5 pounds. Wernher von Braun, the former Nazi rocket scientist brought here after World War II, was immediately ordered to respond with the Explorer at the U.S. Army’s Redstone Arsenal.

On Jan. 31, 1958, the U.S. launched Explorer 1, which discovered the Van Allen Belts, which hold magnetic radiation around the earth. In July, Congress passed the Space Act, which established the National Aeronautics and Space Administration on Oct. 1, 1958.

In the days before a U.S. Department of Education, university presidents and state governors demanded schools do more to prepare students for science and technology, to make them better prepared for the new age. Testing was emphasized as well as new methods for teaching mathematics.

By coincidence, the whole affair took place only slightly after the transistor was invented at Bell Laboratories, then a unit of AT&T Inc. (NYSE: T), and the integrated circuit by two separate groups of engineers, at Texas Instruments (Nasdaq: TXN) and a forerunner of Intel (Nasdaq: INTC), now the No. 1 chipmaker.

In 1960, Sen. John F. Kennedy, D-Mass., used the technology gap and an invented “missile gap” with the Soviet Union to urge the country to “get moving again” and narrowly won the presidency over Republican Vice President Richard M. Nixon. Kennedy put Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson in charge of NASA and a space council, declaring space a vital frontier for U.S. technology.

In September 1962, Kennedy set the U.S. objective of landing a man on the moon by 1970. That was accomplished on July 20, 1969.

To get there, though, required new organs such as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and an electronic method of connecting the government, aerospace contractors, universities and laboratories. Today it’s called the Internet.

That effort also spurred Silicon Valley into existence, brought new advances in propulsion, metallurgy and telephony and led squarely to the miniaturization of electronics. Anyone who’s seen a model of a U.S. space capsule in a museum from the 1960s flights of astronauts like John Glenn is amazed by how primitive they are by 2012 standards.

Without Sputnik, though, Alan Shepard probably wouldn’t have been the first American in space on May 5, 1961 – three weeks after Russian Yuri Gagarin became the first person in space.

The old U.S.S.R. never landed a person on the Moon, nor sent landers to Mars, nor invented Intel. It collapsed in 1991. And Russia and its former satellites still have no equivalent of International Business Machines Corp. (NYSE: IBM), Apple or Hewlett-Packard Co. (NYSE: HPQ).

To its credit, though, the Soviet Union’s Sputnik mobilization provided a needed kick in the pants to an America that wasn’t ready for the future. Fifty-five years later, staying competitive and No. 1 in technology may prove more challenging than ever.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.