How to Measure Galaxy's Distance From Earth?

The speed and direction of a distant galaxy can be easily measured by analyzing light coming from the galaxy. But to determine the galaxy's distance from Earth was much more difficult.

This has been done until now by observing the brightness of individual objects within the galaxy and using what we know about the object to calculate how far away the galaxy must be.

Recently, Florian Beutler, a PhD candidate with the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) at the University of Western Australia, has produced one of the most accurate measurements ever made of how fast the Universe is expanding by using the Hubble constant.

The approach of measuring a galaxy’s distance from Earth by observing the brightness of individual objects within the galaxy was based on some well-established assumptions but is prone to systematic errors. This led Beutler to tackle the problem using a completely different method.

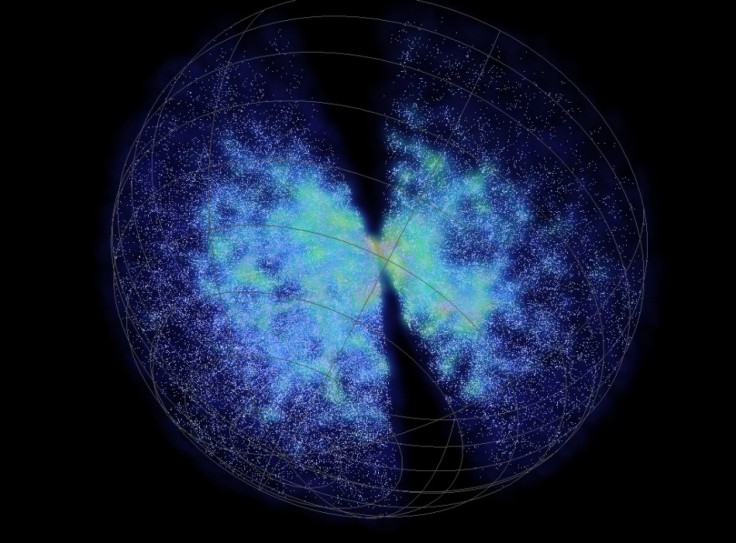

Beutler's work draws on data from a survey of more than 125,000 galaxies carried out with the UK Schmidt Telescope in eastern Australia. This is the biggest survey -- called the 6dF Galaxy Survey -- to date of relatively nearby galaxies, covering almost half the sky.

"The Hubble constant is a key number in astronomy because it's used to calculate the size and age of the Universe," said Beutler.

Galaxies are clustered but not spread evenly through space. Using a measurement of the clustering of the galaxies surveyed, plus other information derived from observations of the early Universe, Beutler has measured the Hubble constant with an uncertainly of less than 5 percent.

"This way of determining the Hubble constant is as direct and precise as other methods, and provides an independent verification of them," said Matthew Colless, Director of the Australian Astronomical Observatory and one of Beutler’s co-authors. "The new measurement agrees well with previous ones, and provides a strong check on previous work."

The measurement can be refined even further by using data from larger galaxy surveys. "Big surveys, like the one used for this work, generate numerous scientific outcomes for astronomers internationally," said Lister Staveley-Smith, ICRAR’s Deputy Director of Science.

Beutler's work was published Wednesday in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.