Pet Shop Bans In San Diego, LA, Albuquerque And Elsewhere Underscore Escalating War On Puppy Mills And Commercial Dog Breeders

Remember that doggy in the window? The one with the waggly tail? In some places, he would now be illegal -- no matter how much he costs.

With a new ordinance becoming effective this week, San Diego is now the second-largest city in the U.S. to ban the retail sale of companion animals. Passed almost unanimously by the San Diego City Council in July, the ordinance makes it unlawful for pet shops and other retail businesses to display, sell or even give away live dogs, cats or rabbits -- unless the animals are obtained by an animal shelter, an animal-control agency, a humane society or a nonprofit rescue organization.

In curbing retail dog sales, San Diego joins Los Angeles, Albuquerque, N.M., Austin, Texas, and more than two dozen municipalities across the country. The bans, all of which have taken effect in the past three years, are evidence of a rapidly growing movement to put an end to so-called puppy mills, a term used by opponents to describe high-volume commercial dog breeders. Animal-rights groups say such facilities, which can move more than 2,000 dogs a week, supply the vast majority of pet-shop dogs. Unsurprisingly, the San Diego ordinance and others like it have attracted fierce criticism from breeders and pet-shop owners who say the anti-pet-shop movement is just plain rabid.

“It’s absolutely absurd,” said David Salinas, owner of the pet shop San Diego Puppy. “It’s the result of an animal-rights-extremist type movement. Nothing we’re doing is illegal.” In a phone interview, Salinas spoke with all the raw acrimony one would expect from a business owner whose livelihood has just been outlawed with the stroke of a pen. He frames the pet-shop ban as a consumer-rights violation, an instance of an overzealous city government butting in where it doesn’t belong. “We’re not Communist Russia,” he said. “Americans should have a right to choose where they can shop.”

Most animal-rights organizations disagree. While differing in their tactics, groups such as the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), and the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS), all share a similar viewpoint when it comes to buying puppies from pet shops: Don’t do it. Ever.

Is that animal-rights extremism? Cori Menkin, senior director of ASPCA’s Puppy Mills Campaign, says no. “To characterize a response like this as ‘extreme’ is unfair,” she told International Business Times. “When you look at the conditions inside many of these breeding facilities, where pet stores are sourcing their puppies, that’s extreme.”

Menkin called substandard dog-breeding facilities a “systemic problem,” a consequence of inadequate protections in the Animal Welfare Act and poor enforcement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, or USDA, which regulates dog breeders. She said “inhumane” conditions at dog-breeding facilities are not simply a case of a few bad apples -- they’re a widespread problem. “We’re talking about an industry that, across the board, is extremely cruel,” she said.

To provide a visual representation of that cruelty, ASPCA this summer launched a database of photographs taken by USDA inspectors at licensed breeding facilities where violations have been found. The growing collection of more than 10,000 images includes breeders’ names, locations, USDA license numbers and information about specific offenses. Users can even look up their neighborhood pet shops to see whether their suppliers have been cited. The images range from mildly disquieting (pictures of overgrown weeds near dog cages) to graphically disturbing (dogs suffering from eye and skin diseases). But together they paint a picture of an industry that seems to, as a rule, put profits ahead of the needs of dogs.

Dog-Whistle Politics?

Pet-shop owner Salinas believes campaigns such as ASPCA’s database of photos are cogs in a powerful propaganda machine. He said such image collections are typical of today’s media-savvy advocacy groups, which he said routinely use selective graphic imagery and television commercials that fail to paint a complete picture. According to Salinas, the goal is not to provide accurate information, but to win public support for an overreaching agenda.

“We all know politics,” he said. “Whether it’s the politics of trying to ban pet stores, or mining, or fur, or any other extremist-type movement, these people are going to do whatever they can to sway the general-public consensus.”

But not all criticism of dog breeders is coming from animal-rights groups. The Office of the Inspector General carried out an audit of the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service’s Animal Care unit, the arm of the USDA that is responsible for enforcing the Animal Welfare Act. According to a scathing audit report published in May 2010, the office said it found “major deficiencies” in the unit’s enforcement practices, including overlooked violations and “lenient practices against repeat violators.”

The report provides explicit details of overcrowded facilities, tick-infested and disease-ridden animals, and graphic images to accompany the descriptions. At one facility, inspectors said they found dogs so starved that they had resorted to cannibalism.

Salinas, who also runs a pet shop in Oceanside, Calif., far north of San Diego’s city limits, acknowledged irresponsible breeders are a problem in the industry. But he said pet-shop bans go too far, punishing shop owners who play by the rules and obtain their dogs from responsible breeders. He added that San Diego Puppy does not do business with breeders that have even a single “direct” USDA violation -- that is, a violation that directly affects the welfare of the dog. However, he admitted that he will do business with breeders that have “indirect” violations. “An indirect violation would be something like the food bowl isn’t covered or there’s a dead fly on top of the food,” he said.

Unimpressed with Salinas’ policy, ASPCA’s Menkin said indirect violations can also include housing conditions. “There can be fecal waste all throughout the cage,” she said. “That is not a direct violation.”

Unleashing A Movement

Five years ago, the notion of banning retail pet sales would have seemed almost ridiculous, at least to the average person. After all, pet shops were once very much a part of Americana. But then so were pet rocks. As evidenced by the above-mentioned ordinances, many of which were passed overwhelmingly, the tide of public opinion is changing -- and quickly.

So why the shift? The Companion Animal Protection Society, or CAPS, takes credit for ushering in the modern movement. Founded in 1992, the nonprofit group exists solely to investigate pet shops and the dog-breeding industry, according to its founder and president, Deborah Howard. In a phone interview, Howard told the IBTimes that the city of West Hollywood, Calif., passed a pet-shop ordinance in February 2010 as a direct result of a CAPS investigation. It wasn’t the first such ordinance, but, at the time, it came with the highest profile.

“We had international publicity on it because it’s West Hollywood,” Howard said. “That’s what opened the floodgates.”

As CAPS notes on its online site, other municipalities followed the lead of West Hollywood, many in Southern California, where CAPS worked with officials in Glendale, Irvine and elsewhere to pass similar ordinances. A CAPS investigation is cited as the impetus for San Diego’s ordinance, as well. The investigation was presented to the city’s Public Safety Committee in March of this year. At the time the ordinance was passed, San Diego had only two remaining pet shops that still sold puppies, one of which was Salinas’ San Diego Puppy. In contrast, Los Angeles had more than 30 pet shops when its local law was adopted.

Howard said that because these ordinances directly affect local businesses, they are exceedingly difficult to pass. She said city council members are swayed only after being presented with overwhelming proof of substandard conditions, either in pet shops or at the breeding facilities that supply them. Her description of the process flies in the face of Salinas’ notion of an irrational, ban-happy animal-rights movement.

“We don’t just go around willy-nilly passing ordinances,” Howard said. “We gather evidence first. Not only do we go undercover to pet shops, but we’ve investigated more than 1,000 puppy mills, most of them USDA-licensed.”

Is Responsible Breeding An Oxymoron?

Dogs are unique among our companion animals. Their genetic code is unusually mutable -- a trait specific to canine DNA, which makes the species subject to rapid evolutionary changes over a short period of time. This trait has allowed humans to mold dogs into whatever style we want, from the towering Great Dane to the tiny Chihuahua, in a matter of decades. In fact, 80 percent of today’s dog breeds didn’t exist before the Victorian era.

But all that molding has come with a price for man’s best friend. Honed over generations for hyperspecific traits, purebred dogs are susceptible to a host of genetic diseases. For instance, the same gene that gives Dalmatians their white fur also puts them at risk for hereditary deafness. It’s no wonder the ostentatious world of pedigree pups is marred by controversy that was highlighted by a BBC documentary in 2008, as noted by the Bark magazine.

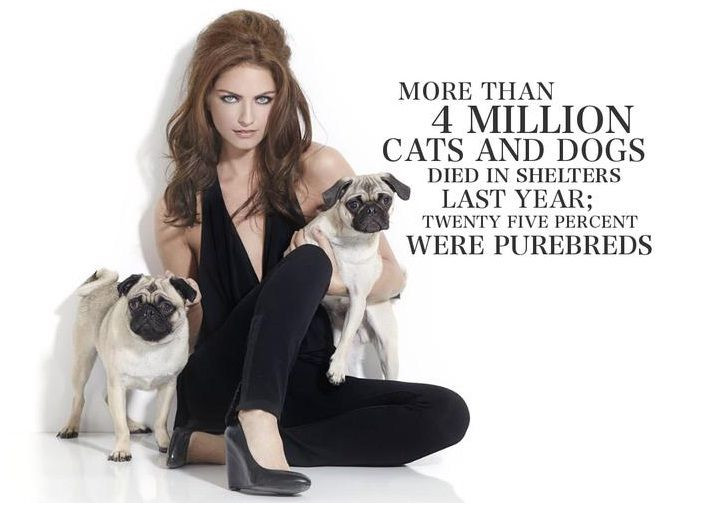

Further fueling the debate is the overcrowding of dog shelters and rescue facilities across the country. HSUS has estimated between 3 million and 4 million dogs and cats are euthanized in the U.S. every year. The gross overcrowding not only represents a failure of the basic tenets of animal welfare, but also burdens taxpayers, as CAPS’ Howard pointed out. It’s another component of the issue that convinces municipalities to agree to retail bans.

“Taxpayer dollars are going toward keeping animals in shelters and to euthanize animals,” Howard said. “So how can we justify all these animals coming out of commercial-breeding facilities?”

Pet-shop owner Salinas doesn’t believe such arguments are presented with the best intentions. He said the real goal behind the anti-pet-store movement is to put an end to purebred dogs entirely, and he believes animal-rights groups will not be happy until all dog breeding is banned.

“These folks believe that breeding is wrong and that you should only adopt,” Salinas said. “The sad thing is it can lead to purebred-puppy extinction.”

At ASPCA, Menkin denied that charge. “That’s an agenda that is attributed to us over and over again, and it’s simply untrue,” she said, pointing to ASPCA’s official position statement for responsible breeding. “We’re not against breeding. We simply want it done responsibly.”

You might ask yourself, then, why the two sides can’t meet in the middle? Couldn’t retail pet sellers peacefully exist if they agreed to sell dogs only from responsible breeders? Therein lies the snag. According to ASPCA’s criteria, a responsible dog breeder is one who deals directly with the person to whom he or she sells. Serving as proverbial middle men, pet shops don’t allow for this.

“As a breeder, you’re giving up the opportunity to screen where the puppy is going, to make sure it’s going to a good home,” Menkin said.

It’s something to think about the next time you encounter a pet store that bends over backward to convince you that its puppies come from the canine equivalent of a country club. Most will -- at least as long as they’re legally allowed to operate. And what are the chances that we’re moving toward a federal ban on retail pet sales? Even Howard doesn’t see that as a particularly realistic endgame, if only because of the commercial breeding industry’s sheer size and lobbying power. But don’t take that to mean that a pet-shop ban isn’t coming to a city near you.

“I do think this ordinance movement is going to continue to grow,” Howard said. “We’re trying to get it passed on the county level now, and if that starts happening, I think more counties will move forward.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.