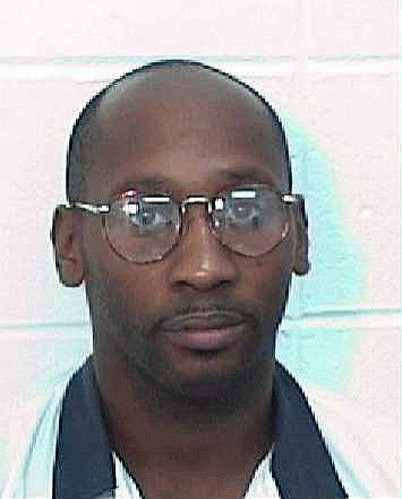

The Troy Davis Case Fuels Debate on Reliability of Eyewitnesses

Georgia officials executed Troy Davis last week for a 1989 murder case that was almost entirely based on eyewitness testimony. Now, more than 20 years later, legal experts say Davis' story is another example in a debate about how reliable are eyewitnesses' testimonies, especially in death penalty cases.

Hundreds of thousands of supporters of Davis, which included ordinary citizens, death penalty advocates and human rights organizations, were left outraged that the state of Georgia put to death a possibly innocent man in a controversial case where no DNA evidence and murder weapon were found.

There's going to be some broader discussions about whether the death penalty is viable at all, but before that happens there's going to be efforts to reform and see what can be done in states that believe in it and regularly use it, Richard Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, which opposes capital punishment, told USA Today.

Prior to Davis being executed last Wednesday, some stated had already reduced their reliance on testimonies from eyewitnesses.

The USA Today article noted that last month, the Supreme Court of New Jersey issued a ruling to make it much easier for criminal defendants to get pre-trial hearings that challenge the credibility of eyewitness evidence.

That court, which abolished the death penalty in 2007, also made it a requirement for judges to give juries more detailed instructions regarding the potential flaws in eyewitness identifications, according to the USA Today article.

Similarly, Maryland lawmakers back in 2009, barred prosecutors from pushing for death as a punishment to a crime unless they have DNA evidence. They are also requiring a videotape of the crime or a videotaped confession from the suspect.

Eyewitness testimony is so horribly inaccurate - even under the very best of circumstances, Rob Warden, director of the Chicago-based Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University, told USA Today. We should never depend on eyewitness testimony in death penalty cases.

The center told USA Today that of the 138 defendants sentenced to death for murder and then later exonerated nationally since the mid-1970s, 32 were convicted as a whole or partly based on erroneous eyewitness testimony.

The state of Georgia accused Davis, 42, of murdering police officer Mark MacPhail in 1989. He was convicted of the crime in 1991.

Since his arrest, Davis has maintained that he was an innocent man, and in the death chamber his pleas didn't change.

While on his death bed Davis told the officer's family that he was sorry for your loss, but I did not personally kill your son, father and brother. I am innocent.

The incident that night was not my fault, I did not have a gun, Davis continued saying to all who had gathered for the execution.

Realizing there was no escaping his judicial killing, even after defense attorney filed a last-minute request to have Davis take a polygraph test, Davis urged people to continue to fight and look deeper into this case so you can really can finally see the truth.

When the state of Georgia tried Davis for murder nine witnesses testified seeing his pull the trigger, Since then, seven of nine witnesses have recanted their testimony, saying police forced them to identify Davis as the triggerman.

I got tired of them harassing me, and they made it clear that the only way they would leave me alone is if I told them what they wanted to hear, said Jeffrey Sapp, one of the witnesses who later recanted his story. I told them that Troy told me he did it, but it wasn't true. Troy never said that or anything like it. When it came time for Troy's trial, the police made it clear to me that I needed to stick to my original statement; that is, what they wanted me to say. I didn't want to have any more problems with the cops, so I testified against Troy.

From the way the officer was talking, he gave me the impression that I should say that Troy Davis was the one who shot the officer like the other witness [sic] had... I felt like I was just following the rest of the witnesses, said Dorothy Ferrell, another witness in the case. I also felt like I had to cooperate with the officer because of my being on parole...I told the detective that Troy Davis was the shooter, even though the truth was that I didn't see who shot the officer.

USA Today interviewed Gary Wells, a psychology professor an Iowa State University who studied 497 examples of witnesses to real crimes. They were looking at lineups on police computers in four states.

What Wells found was that when witnesses looked at a group of photographs all at one, they tend to compare faces and pick the one that most resembled the suspect. This is regardless of whether it was correct or not.

That rate of wrong identifications is reduced from 18 percent to 12 percent, according to the USA Today article, when witnesses are able to look at the photographs one at a time.

Willis believes this single approach would make in-person lineups more reliable, and also if the officer who is working with the witness isn't aware of who the suspect is.

These kinds of events that people witness, whether a victim or a bystander, often happen very quickly, they're unexpected, Wells told USA Today. It's not like the only thing to look at is the perpetrator's face. There are other things going on; people fear for their safety.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.