Very Strange Bedfellows (North Korea Included) Ponder How To Escape Media Decline

What does the future of global media look like? Few mega-media organizations know the answer, many have different goals in mind, and everyone is trying to avoid death or irrelevancy by Twitter.

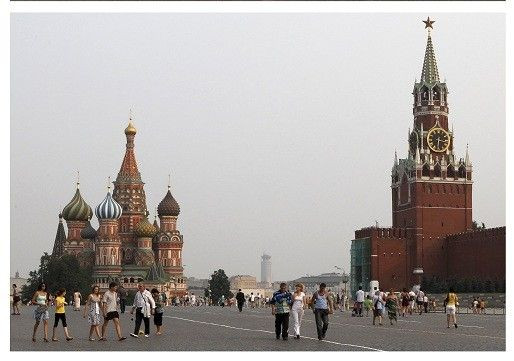

With that in mind, over 300 representatives of 213 media outlets from 103 countries descended on Moscow the past week (July 4-7) for the second World Media Summit. Many were the top executives, directors or management leaders of their organizations -- including one from North Korea, arguably the least free state in the world.

First on everyone's mind was how mass media companies of the 20th century could adapt and remain competitive in the 21st, an age where social media, blogging and other non-traditional networks are challenging their dominance of the information space. But everyone had their own agenda and their own message to push.

Varied Welcomes

The event was hosted by a media outlet familiar to those who grew up during the Cold War: ITAR-TASS, once the official news agency of the Soviet Union with the name of TASS, reborn in 1992 with a slightly different name under the newly democratic Russian state. Today the International Telegraph Agency of Russia - Telegraph Agency of Communication and Messages is a major Russian media group with strong links to the government. The agency hosted the event at Moscow's glitzy World Trade Center. The first World Media Summit, in 2009, took place in Beijing.

If China and Russia don't come to mind as bastions of journalistic innovation or freedom of speech, Vladimir's Putin's welcoming remarks on July 5 may have raised even more eyebrows.

Russia's newly re-elected strongman president, during whose rule several journalists have been murdered in unsolved crimes, offered the following advice: I believe it is very important the agenda of the summit includes such key issues as the evolvement of ethical norms for the mass media community... [including] enhancement of the guarantees of impartiality and independence of journalism, guarantees of the freedom of speech, the promotion of an equitable and constructive dialogue with bodies of state power, business circles and non-governmental organizations.

Ban Ki-moon, the secretary-general of the United Nations, minced no words addressing the assembled parties with comments on the same day that seemed subtly aimed at the host nation.

Ban mentioned that over the last decade, we are also seeing rising threats to press freedoms and media professionals. ... More than 500 have lost their lives. Sixty-six were killed this year alone. Countless others have been detained, threatened or silenced through fear and censorship.

The Russian government has received widespread condemnation over recent years from non-government organizations as being unfriendly and even hostile to journalists.

Journalists are under threat not only in conflict zones, but when they report on governments, police and businesses -- or drug cartels and arms merchants, said Ban.

But the main concern of the summit was not how to better protect journalists through policy or legal mechanisms. Debate was instead focused on how to save big media businesses amid an unprecedented challenge from average global citizens, who can now make and transmit news themselves, and from the global recession, sapping the coffers of media groups worldwide.

West And East Together

Nine huge media organizations -- the Associated Press, BBC, ITAR-TASS, Kyodo News, News Corp., Thomson Reuters, Turner Broadcasting System Inc., Xinhua, and Google, which is now de facto a media outlet as well as a search engine -- started the WMS process in 2009. Al-Jazeera and the New York Times joined the group respectively in 2010 and 2011. The head of China's Xinhua, a state-run news agency, acts as the WMS' executive chairman, and his peers co-chair the conference.

That's an eye-opening list. The Western organizations mentioned above often criticize their Chinese or Russian counterparts for being mouthpieces of regimes that sideline and crush real journalism. Chinese and Russian media giants often reply that Western media are biased, overly sensational, and selectively critical of conditions in their countries, blinding them to more relevant stories.

That those two, supposedly diametrically opposed, camps would now be strategizing together is revealing of the deep concerns gripping big media about how to handle the news business in a new era.

Rivals and competitors are being forced to sit together to discuss their common enemy -- the average man or woman with a cell phone or a social media account and a propensity to express his/her thoughts.

The senior managing editor for international news at the Associated Press, John Daniszewski, mentioned to ITAR-TASS on July 5 that he saw his company as a filter for accurate news. In an age of Twitter, many people are participating in a global discussion, which is a very good thing, [but] you need to have some agencies that will actually say this has actually happened, and this is false, this is a rumor, said Daniszewski.

But the editor was also confident in saying that he thought no amount of technology would be able to substitute for a well-trained and impartial reporter.

Pavel Gusev, editor-in-chief of Moskovsky Komsomolets, had a blunter approach. As for the stuff one finds in the social networks, it is unreliable as a rule, he told ITAR. Gusev remarked that if we ruin journalism to give way to the social networks, where 'somebody has heard something somewhere,' we shall upset the balance of information and economic security.

But regardless of whether corporate media leaders hold disdain in their hearts for the decentralization and leveling of the news world, nearly everyone sees the current trend as irreversible.

The director of the BBC World Service, Peter Horrocks, warned that sticking to antiquated views and methods on how to control information flows would only result in defeat in the competition with new communication media.

Susan Taylor, president of Reuters Media, said new technologies are bringing huge challenges and huge opportunities. We need to think about user-generated content, we need to be thinking about social media, and how we can interact with this new technology, she said.

And NBC Vice President David Verdi noted that social media could act as a new delivery system for traditional journalism.

Ironically, for a conference focused so deeply on the new media, it failed on the basics of using them to provide coverage. The summit was not live-streamed.

Divergent Aims

ITAR-TASS Director General Vitaly Ignatenko placed as a major agenda item of the WMS the discussion of media-business-state cooperation.

Inequality of some countries and even regions in the sphere of information remains, he said.

Many would retort that the true role of journalism has nothing to do with cooperating with businesses and the state. It should instead be critical of those interests. For those suspicious of the links between Russia's media companies and its politicians, Ignatenko's comments seemed an attempt to influence the discussion, to the benefit of the government's political and corporate interests.

But if Ignatenko offered a questionable assessment of journalistic responsibilities in this case, he certainly wasn't the only one.

Chang Tegan, Asia-Europe chief for Xinhua, said cooperation amongst various media organizations was critical during the formation of a multi-polar world.

What does the balance of geopolitical power have to do with providing the news? Nothing, say the critics, unless you're a Chinese company eager to gain global recognition as a professional news service, thereby gaining more prestige for your state backer.

Sergey Naryshkin, chairman of the Russian parliament, the State Duma, said the Moscow-hosted WMS was recognition of a special role of Russia and Russian media on the world media landscape.

Indeed, much of the conference had nothing to do with the status of the international media at all, but was instead a forum for various national agencies to push for recognition of their legitimacy.

Li Congjun, president of Xinhua, said in a speech on July 6 that reporting should be accurate, objective, fair and impartial. The fate of the media is closely connected to that of the world, and the media's development must keep pace with the development of the times, said Li. That certainly sounded agreeable.

Li offered that international media should focus more on issues affecting children, women, poverty, disease, education and environment. All issues that should be reported, to be sure. But government intrigue and corruption were curiously absent from Li's list.

Still, it would be unfair to be harshly critical of Russian and Chinese news agencies. Those countries have made impressive strides in recent years to reform the media, and many organizations within those countries are also increasingly critical of their governments and open to deeply investigative pieces that touch upon sensitive social and political issues.

But the same really cannot be said for North Korea, also represented at the conference.

The North Koreans Show Up, Too

Kim Pyong Ho, director general of the Korean Central News Agency, the North's government-backed news group, stated that mass media should contribute to the development of harmony, equality, friendship among countries and people across the world.

Kim noted that It's vitally important that the media strictly adhere to the principles of entirety and precision in presenting information so as to fulfill its role in forming public opinion. He opposed the domination of the international news space by any one group.

When North Korea, China, and Russia talk about impartiality, equality, and objectivity in the news industry, what they really mean is political fairness. The domination of the international news space by Western media outlets (although shrinking), creates challenges for state-backed media organizations working to improve the image of their own governments.

Yet giving the government a fair voice has no role within the fourth estate, which is meant to serve an independent role keeping state power in check.

That raises an important question about the WMS as a meaningful forum. Does cooperation between Western media organizations and their state-backed counterparts at these summits inherently legitimize the latter? It is true that all media organizations are facing challenges from social media, but only some represent government interests that are endangered by those networks.

Janis Karklins, Unesco's assistant director general for communication and information, instead offered that the media ought to assume a greater role supporting democracy, fighting corruption, building transparency, and giving attention to human rights abuses. Yet none of those were core issues covered by the summit.

The third World Media Summit in 2014 is expected to be held in Bahrain, deep in a part of the world where social media have already gained notoriety for their enormous effect on politics, helping spur the Arab Spring revolutions.

Bahrain isn't a hub for the freedom of the press, either. But the tiny kingdom's Information Minister Samira Rajab noted that It is vitally important that it [the summit] will take place in an Arab country. The Arab world needs media attention because it has become a scene for events that are crucial for the whole world.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.