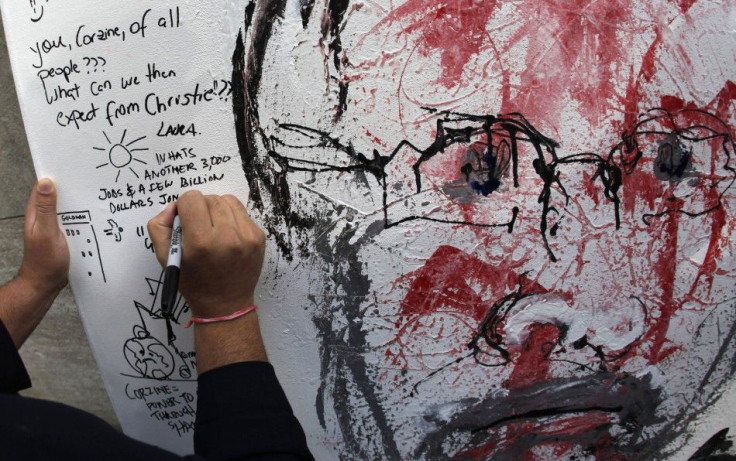

Who Killed MF Global? Corzine Blames Nearly Everyone but Himself

Commentary: Corzine Points Finger at Consultants, Accountants, Regulators, Predecessors

As he prepares to testify before a Congressional committee regarding the fall of MF Global Thursday, Jon Corzine’s prepared remarks pin the blame on just about everyone else but himself.

Outside consultants, accountants, regulators, and people who were at the company “before I arrived” all took actions that undermined the stability of the company, Corzine is set to tell the House Committee on Agriculture today, according to his written comments.

However, not responsible are “one of the recurrent themes in the media” -- the firm’s relatively high ratio of leverage or its exposure to European sovereign debt, states the former MF Global chief.

In his remarks, the one-time U.S. senator says he will abstain from taking his “constitutional right to remain silent” as he “recognizes the importance of congressional oversight.” He does make it clear that he might not be able to answer all the Congressmembers’ questions. Preempting what will likely be the committee’s first question, about the funds missing from what were supposed to be untouchable customer accounts, Corzine writes “I simply do not know where the money is.”

Blame It On The Help

An old adage in management consulting circles says that “no one ever got fired for hiring McKinsey," a reference to the common business practice of bringing in outside consultants to make important and controversial strategic decisions.

Jon Corzine’s statements disagree with this logic, blaming the Boston Consulting Group, one of the most respected business consultancies in the world for setting them on a path he calls “the new business plan”: to “evolve into a broker-dealer, and ultimately into an investment bank.” Another consulting, Promontory Financial Group, gets tarred for any failures in compliance with regulators.

The accountants also share some blame in Corzine’s retelling of the MF Global collapse. “I do not claim to be an accountant,” Corzine states in his written testimony as he explains how certain transactions (so called repo-to-maturity, or RTMs) meant to take some risk off the books were noted in the balance sheet, but he “believe[s] that accounting issues with respect to the RTMs would have been reviewed by MF Global’s internal auditors, outside auditors (PricewaterhouseCoopers), and its audit committee.”

And The Regulators Too

A substantial amount of Corzine’s denunciation also goes against federal financial regulators for, essentially, moving the goal post. More than three out of the written testimony’s 18 pages are dedicated to noting how actions by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), an industry regulatory group, and the government’s Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) suddenly implemented rules that forced MF Global to account for their risk, forcing the company to decrease its leverage.

Corzine paints the regulators as somewhat unresponsive, noting that after meeting with FINRA to ask for a delay in implementation of new rules, a regulator told him there would be no appeal of the decision. He also notes the regulator, Michael Macchiaroli, told him that he could send a letter to the Securities and Exchange Commission but “was clear that such a letter would make no difference to FINRA’s or the SEC’s position.”

Almost Forgot: The Guy Before Me

Corzine rounds out his prepared remarks noting the exposure to European sovereign debt was not what took MF Global down, but instead, the company mainly suffered from having to write down nearly $120 million in losses accumulated “mostly before I arrived at MF Global.”

Corzine finishes his statement the same way he began, apologizing to those that suffered losses as a result of his former company’s implosion.

As for taking responsibility, he does so at two points, noting he was responsible for the RTM trades and had “ultimate responsibility” for the firm’s actions as its chief executive. He couches this final statement, however, noting “I did not […] generally involve myself in the mechanics of the clearing and settlement of trades.”

There’s an apocryphal story that, upon leaving office, former Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev left two sealed letters to his successor, with instructions to open them, in a specific order, whenever a crisis appeared to overwhelm the Russian leadership. In the tale, the first letter was simple, containing instructions to “Blame me for the mess.” The second letter, however, counseled the leader to “sit down, and write two letters.”

Perhaps it might be time for Corzine to open that second letter.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.