How Has The Cruise Industry Changed In 100 Years?

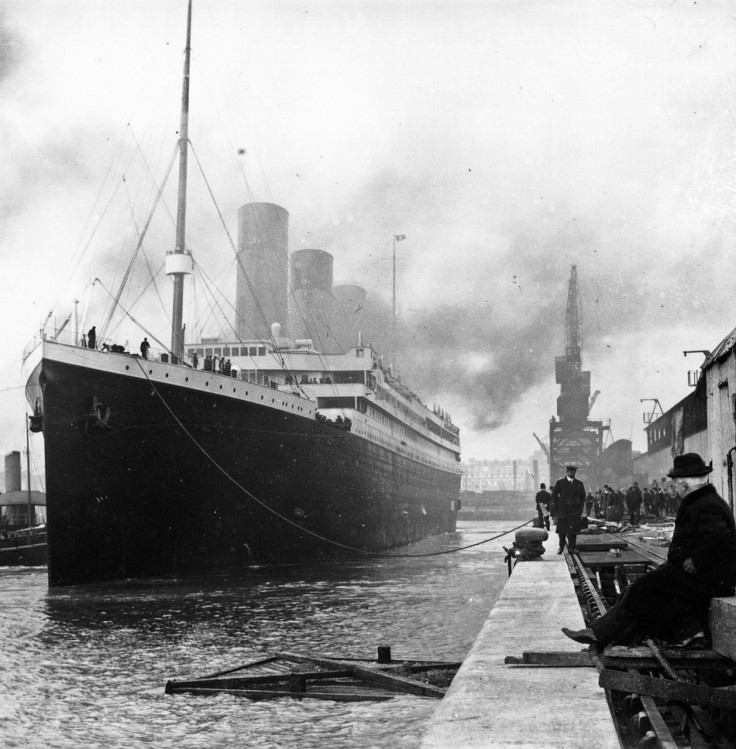

The 100th anniversary of the Titanic sinking is a good time to look back at how the cruise industry has changed in the past century. With modern technological advances and innovation, it's easy to see that the industry has made improvements -- at least on the outside. But a deeper look at the state of cruising today points to an industry that has slowly spiraled out of control.

In many respects, it's remarkable how little has changed in 100 years. The Costa Concordia disaster was proof of that. In both cases, the ship took on water, passengers fled their cabins, and there was widespread panic over the best way to evacuate the vessel. In 1912, the ship hit an iceberg; in 2012, it struck a rocky reef.

While major nautical disasters are still a reality, the fatality rate has gone down considerably: More than 1,500 people died when the Titanic sank in the North Atlantic. A hundred years later, just 32 were killed on the modern luxury liner as it ran agound off the Tuscan Coast.

Yet, the incident reminded us that large-scale disasters are not just a thing of the past. Indeed, 2012 kept reminding us of that. Following the Costa Concordia disaster, another Costa ship, the Allegra, was left drifting in pirate-infested waters off Seychelles in February after a fire on board. Another fire on the Azamara Quest left that boat stranded in late March. All of this occurred in a year where eyes were glued to the cruise ship industry.

The current cruise troubles come in the wake of a major industry-wide boom over the past decade that saw over 16 million passengers in 2011, according to the Cruise Lines International Association. But to understand where the industry is now, it's imperative to look back 100 years at the Titanic disaster to see how far it's come.

Why the Titanic Sank

The Titanic sinking had as much to do with human error as it did with how the ship was built.

When Titanic was designed in early 1908-09 at Harland & Wolff, certain standards were to be followed based on the British Board of Trade regulations, which were established before the turn of the last century, said Mike Ralph, co-founder of the Titanic International Society and former writer for magazines like Cruise Digest and Porthole.

These standards of safety were based upon the tonnage of a vessel. At that time, no passenger ship exceeded more than 15,000 to 17,000 tons. For vessels of this size, a maximum of 16 wooden lifeboats were to be carried under davits. Even when the two new Cunard liners Lusitania and Mauretania were conceived and built in 1905-07, they were considerably larger at 32,000 tons, but they only carried the required 16 boats. There was a distinct lapse of judgment.

Alexander Carlisle, Titanic's chief designer, had actually made provisions for carrying of over 48 lifeboats, anticipating that the rule would change. It did, but not for reasons he could have imagined at the time.

His designs were rejected as being too extravagant and a waste of valuable deck space for passengers to promenade on.

This was one of many examples of hubris in the tale of the Titanic, which managing director of the White Star Line, Joseph Bruce Ismay, called her own lifeboat.

The first four compartments could be flooded and the ship would not sink, Ralph said. However Titanic had a major design flaw in that her watertight bulkhead in the very next compartment, boiler room number 6, was only carried 10 feet above the waterline.

Collectively, designers agreed that they could only conceive of any two adjacent compartments being flooded at any time during a collision or grounding. When Titanic side swiped the iceberg, five compartments were open to the sea.

That breech of that fifth compartment spelled her end as those bulkheads were not high enough to impede the rising water, Ralph said. The weight of the flooded compartments would pull the bow of the ship deeper under water and each compartment would flood one after the other until Titanic sank.

The Aftereffects

The immediate effects of the Titanic disaster were catastrophic to the shipping industry and within days new laws were passed on both sides of the Atlantic that would forever change the ways ships could operate.

All ships would need sufficient lifeboats for all persons carried on board, and lifeboat drills would be held for the crew and passengers at least once each voyage. Each cabin would be assigned to a particular lifeboat and have posted procedures for the evacuation of the ship. Furthermore, there would be no more catch as catch can in the evacuation of the vessel, and while women and children first would still be the priority, there would be enough places for all of the men as well.

The Marconi Corporation was criticized for allowing ship's navigational traffic to wait until it was convenient for delivery. In the wake of the disaster, all passenger ships would be required to have wireless capabilities and have enough operators to man the equipment on a 24-hour basis. Moreover, all messages received pertaining to the safe operation of the ship would be passed to the officers on the bridge immediately.

No matter who or what is to blame, Ralph remarked that there is only one true rule of the sea: eternal vigilance must be maintained at all times.

The State of the Cruise Industry Today

Today, the cruise industry is in a totally different place. Though it's seen massive growth, many see this as a double-edged sword, questioning whether the ships have grown too big to handle. Others argue the industry is far less regulated than, say, air travel, and they are calling for sweeping industry-wide changes.

In some ways, the current industry isn't all that different than the days of the Titanic, said Ross A. Klein, professor of social work at the Memorial University of Newfoundland and an author of four books on the industry, including Cruise Ship Blues: The Underside of the Cruise Ship Industry.

They were arrogant, Klein said. It was unthinkable. I think people have that same arrogance today.

Klein was a self-described cruise junkie in the 1990's and was cruising up to 45 days a year by 1996. A sociologist by training, he began to analyze what was going on.

I was seeing the same faces each time and began to see things that were incongruent to what was in the advertising. What the cruises said they were doing wasn't what they were actually doing -- and nobody had written anything about it.

So in 1998, he made studying cruise ships his area of research. By 2002, Klein had uncovered so much dirt on the industry that he was advised that he was no longer welcome on cruise ships.

I don't want to test the waters, he joked. I don't want to be a statistic of a person overboard!

Statistics are something that he agonizes over on his website, cruisejunkie.com, and they're something he's been called to the Senate floor to testify about.

Klein said that the common notion that cruising is the safest mode of transportation is a matter of perspective. According to his statistics, 16 cruise ships have sunk since 1980, 99 have run aground since 1973, 79 have experienced onboard fires since 1990 and 73 have had collisions since 1990. Since 2000, there have been 100 cases in which ships have gone adrift, lost power, experienced severe lists, or had other events that posed a safety risk.

I would concede, he added, that generally speaking, the incidents do not lead to many deaths.

However, he pointed to issues on the Costa Concordia for proof that there are still glaring problems with passenger safety. Why didn't they have a safety drill before leaving the dock? Why did they depart with a black box that the captain said had been broken for 15 days?

And then there's the issue of the large boats. Have boats become too massive to handle accidents?

It's not the issue of size per se, but if you are going to be that large, are the hallways large enough? Are there enough stairwells? The traditional construction is four main stairways -- does that model make sense on larger ships?

He pointed to a lack of concrete empirical evidence as another form of hubris that dates back to the Titanic.

But there are other issues that we don't think about as much, like environmental impact or the exploitation of workers.

Navigating through international waters, the rules governing cruise ships are decidedly murky.

Today's business model began as early as the 1920s with the transition to flags of convenience. A cruise liner like the Titanic would have had a crew from the nation whose flag graced the top of the ship. Now, ships registered to places like the Bahamas and Panama are the norm. By doing so, ship-owners found they could skirt increased regulations and rising labor costs, while avoiding paying federal taxes to the nations out of which the ships actually operate.

Under this system, the only labor laws that would apply to a ship would be those of the nation it's registered to. In the mid-2000s, following the settlement of Borcea vs. Carnival, the cruise industry began to include arbitration clauses in cruise ship workers' contracts, making it even harder to settle grievances.

Klein noted that these employees could have a mandatory 77-hour work week and earn very little in return -- at least by Western standards. Living conditions and food quality have certainly improved since the days of the Titanic, but statistically, the remuneration is about the same -- or in some respects poorer -- than in 1912, accounting for inflation.

In terms of environmental impact, it would be hard to argue that ships aren't more green-minded these days, but the cruise industry is incredibly larger than it used to be, and there are a wide range of issues involving the discharge of waste, sewage and oily bilge. While regulations are relatively stringent in Alaska, Washington and California, there is little regulation in the Gulf States and much of the Eastern Seaboard.

The problem with regulating these factors once again lies with where the ship is registered. Enforcement of a cruise ship's environmental standards under the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, known as MARPOL, is often inconsistent, and it is not the responsibility of the country where the ship operates, but rather the nation whose flag it bears.

These are all things that Klein and others have spoken out against for years.

But few have listened. Sometimes it takes a big event like the Costa Concordia disaster or the Titanic anniversary for us to step back and question where we were and where we've come. And sometimes, the latter may not be what we'd like to hear.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.