If Pence Shapes Trump’s Infrastructure Plan, Who Would Profit? Who Would Pay?

President Donald Trump’s $1 trillion plan to rebuild America’s infrastructure may be unprecedented in its size and ambition, but it promotes a controversial model championed by Vice President Mike Pence in his home state of Indiana. The Hoosier flavor is hardly surprising: After his gubernatorial experience with road privatization, Pence has been a public face of the White House initiative, and executives from financial firms that helped privatize Indiana’s roads are now the Trump administration officials sculpting the details of the national plan.

As that federal proposal now moves forward, Indiana’s experience with infrastructure privatization has become a political Rorschach test. Pence and his allies are extolling Indiana’s record selling control of major roads to private firms as an ideal model, arguing that such public-private partnerships prompted corporations to invest money in Indiana infrastructure that taxpayers would otherwise have had to sponsor.

Read: Foreign Firms Stand To Benefit From Trump Budget, Infrastructure Plans

“Indiana has been a national leader in this area where you use private capital to build infrastructure,” Pence told one conservative radio host just after the 2016 election, signaling his eagerness to get started.

But opponents of privatization have depicted Indiana as a heartland cautionary tale of get-rich-quick scheming and secrecy that led the state to sell off valuable public assets, which were then wildly mismanaged. To them, the Indiana story reveals the ideological zealotry of a politician who is now a driving force behind an infrastructure program that could radically reshape local economies and commerce in communities across the country, and for generations to come.

Pence believes in “this religion — the magic and mystery of markets is solving all the problems,” said Shaw Friedman, who represented Northwest Indiana counties’ unsuccessful efforts to press the Pence administration to let public entities reclaim the Indiana Toll Road when its private operator went bankrupt. “They allowed a philosophical aversion to the public sector bid."

Public-private partnerships (P3s) involve private companies investing in, constructing and/or maintaining public assets such as roads, bridges and airports — in exchange for those companies pocketing tolls, fees or other public revenues generated by the assets. The model, sometimes called “asset recycling,” has been more prevalent in Australia, Asia and Europe. In the U.S., use of such partnerships has been “limited,” according to a 2014 Congressional Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure report. But since the turn of the 21st century, more cities and states have begun to embrace such deals. The number of P3s underway in the decade after 2000 more than tripled in comparison to the previous 10-year period, according to a newsletter from Public Works Financing, which compiles a database on P3 projects.

Few states have been as aggressive as Indiana in embracing public-private partnerships. In a state whose official motto, “Crossroads of America,” explicitly touts its highways, recent complications with road privatization projects illustrate how the approach is not always as simple or successful as its boosters would have it.

Only weeks after Pence visited Australia to promote Trump's infrastructure plan to foreign investors, the I-69 privatization deal that he championed — which involved a Pence-connected corporate law firm — collapsed after months-long construction delays, allegations of financial mismanagement and a surge in traffic accidents. At the same time, a foreign firm Pence approved to run the Indiana Toll Road announced it would be hammering economically battered Northwest Indiana with toll increases. The move came just a few years after Pence’s administration approved that corporation’s bid to keep the road under private control — and after Pence's administration rejected local Indiana governments’ efforts to reclaim the road for the public.

Pence’s decision to re-privatize the toll road came even as audits by the company operating the road reviewed by International Business Times catalogued a spike in infrastructure deficiencies on the road after it was originally leased to private companies. Other documents obtained by IBT show that as local governments made their pitch to take back the road, Pence’s administration blocked the release of a state-sponsored, independent cost-benefit analysis of continued privatization — all as the lobbying firm for the road’s private operator delivered more than $100,000 to Pence’s gubernatorial campaign.

The two road deals are precisely the kind that Trump’s infrastructure plan aims to expand under the direction of a team with ties to Indiana privatization. Along with Pence, White House officials Gary Cohn and D.J. Gribbin are spearheading the national proposal to let private firms invest in, operate and/or purchase public assets. Cohn and Gribbin worked for two companies — Goldman Sachs and Macquarie — that originally helped privatize the Indiana Toll Road. Gribbin also worked for Koch Industries, the multinational conglomerate run by billionaire conservative donors Charles and David Koch. The Koch brothers have ties to Pence as well.

Friedman said that with Vice President Pence spearheading the Trump administration's federal infrastructure plan, “It’ll be the same thing. He’ll want to turn over public roads, public bridges to the private sector.”

The U.S. “Is Poised To Become The Largest Public-Private Partnership Market In The World”

As the debate over infrastructure policy intensifies, there is no dispute that the Trump administration’s initiative could open up a huge new market for financial firms on Wall Street. The American Society of Civil Engineers estimates that there are $4.6 trillion worth of needed investments to maintain and upgrade infrastructure throughout the U.S. In light of that, recent reports from Moody’s and AIG project a financial jackpot for private investors, with the latter predicting that America “is poised to become the largest public-private partnership market in the world for infrastructure projects.”

That market appears to be a ripe profit opportunity for politically connected firms. On top of Pence’s overtures to investors in Australia, a country that has aggressively embraced privatization, Trump recently secured a pledge from Saudi Arabia’s government to invest billions in American infrastructure.

The Saudi money is slated to flow through the private equity firm Blackstone Group LP, which has been eyeing opportunities to profit from American infrastructure privatization since its CEO, Stephen Schwarzman, was named by Trump to run a White House economic advisory panel shaping federal infrastructure policy. At the same time, Cohn’s former employer, Goldman Sachs, has said in its financial filings that it too has plans to expand investment in privatized infrastructure. (Neither Schwarzman or Cohn have recused themselves from working on White House infrastructure policy that could benefit the firms, even though both own stakes in the companies.)

In the United States, the recent enthusiasm for public-private partnerships has stemmed from the visible success of several late-1990s toll road projects such as California’s State Route 91, the first fully-automated toll road with electronic transponders in the U.S., and Virginia’s Dulles Greenway, according to Robert Poole, the director of transportation policy at the libertarian Reason Foundation. More recently, he noted, states like Florida have enacted laws streamlining the legislative approval process for public-private partnership transportation projects.

Both the GOP and Democratic Party listed infrastructure spending as objectives in their 2016 platforms. The Republican platform explicitly embraced public-private partnerships and “outside investment.” Prominent Democrats from former President Barack Obama to Bill and Hillary Clinton have also warmed to the idea of public-private partnerships — and the party’s officials have led some of America’s earliest precedent-setting privatization projects.

One of them was a 2008 plan led by Democratic Mayor Richard Daley, which awarded 36,000 Chicago parking meters to a consortium led by Morgan Stanley for a term of 75 years for about $1.16 billion. The lease agreement included a doubling — and in some cases quadrupling — of meter rates during the first five years of the contract period, according to a report by the city’s inspector general. The same report noted that “the city was paid, conservatively, $974 million less for this 75-year lease than the city would have received had it retained the parking-meter system under the same terms that the city agreed to in the lease.”

There was also Daley’s Chicago Skyway plan, which leased the roadway for $1.8 billion for a 99-year period, and which has led to many toll rate increases in recent years.

“The Chicago Skyway and the Indiana Toll Road really shed light on the U.S. as a place where these projects could be done,” Poole said in a recent interview with IBT. “I think it’s kind of a demonstration effect.”

“An Astonishing Sum”

No project better embodies the Trump administration model, and its inherent challenges, than the Indiana Toll Road, a 157-mile highway that serves an area with more than 15 percent of America’s total population. The story of the Indiana Toll Road’s privatization is one that could be replicated in communities across the country — if Trump’s infrastructure plan is ultimately approved by Congress.

That initiative to privatize the so-called “Mainstreet of the Midwest” was originally launched by then-Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels promptly after he was elected in 2004 with the help of business-funded groups like the Republican Governors Association (RGA). An anti-tax crusader who served as George W. Bush’s budget director, Daniels was seeking a way to raise revenues for new road construction and maintenance without raising taxes.

Within months of Daniels’ 2005 inauguration, his administration announced it had given a contract to Goldman Sachs to begin the process of soliciting bids to privatize the toll road. The day before the announcement, the bank made a $50,000 donation to the RGA, its single largest donation to the group at the time. Goldman Sachs would go on to reap $20 million in fees from Indiana taxpayers.

In pushing the deal, Daniels’ administration estimated that, kept in state hands, the road would generate $1.92 billion in revenues over the next 75 years. When bids came in, Daniels’ administration ultimately opted to accept a $3.85 billion bid to run the road by Spanish firm Cintra S.A. and Australia’s Macquarie Infrastructure Group. At the time, Daniels called the bid “an astonishing sum” and said that “partisanship and negativism will now be suspended to seize this fantastic opportunity.”

Though they were offering Indiana a huge upfront outlay of cash, the companies were equally bullish on the deal and what it might represent for future business prospects. An analyst for Macquarie labeled his report on the agreement “Acquiring America.” The Sydney-based investment bank projected an internal 12.5 percent rate of return for investors. The lease guaranteed the companies control of the road for 75 years, effectively exempted the new private consortium from state open records laws and gave Goldman Sachs exclusive rights to financial intermediation, but gave the state the right to take back the road in the event that the companies filed for bankruptcy.

As Daniels sought House votes for the privatization plan, he faced staunch opposition from Democrats.

“This is a 75-year surrender of an interstate highway and all the [toll] revenue we could have brought in,” House Democratic leader Patrick Bauer said at the time. “If there is any ‘wow,’ it’s the new sign that says ‘Indiana for sale or rent’.”

Daniels, for his part, reassured wavering lawmakers, telling Governing Magazine in 2006 that if “the leasing consortium goes bankrupt, the toll road reverts back to the state’s control.”

His push was successful: The bill approving the lease eventually passed by narrow margin in the state house and senate. Daniels celebrated its passage, promising that the new resources would fund priorities across the state. In a speech that same year, Macquarie’s D.J. Gribbin — now the White House aide working on infrastructure — told an Indianapolis audience that, moving forward, “We're very interested, obviously, in new acquisitions.”

Not everyone was certain of success.

“Nobody knows what will happen in 75 years,” Daniels’ own finance director, Ryan Kitchell, told Governing at the end of the year. “There might be flying cars that don’t use the toll road, and we’ll look really smart. Nobody knows."

Others continued to warn that the deal could go bad for taxpayers. A report by Northwest Financial, for instance, found that the consortium was relying on punishingly steep toll increases to recover its investment, and also warned that Indiana could lose transportation revenues over the long haul.

“Indiana’s sale of the toll road, while helping fund transportation projects for the next 10 years, will result in depriving the public transportation funding network of very large and much needed future revenues in the final 65 years of the concession agreement to pay for publicly needed capital projects both on and off the toll road,” the report said. “Instead these revenues are directed to private corporate profits and shareholders.”

Over the next few years, the new revenue from the deal funded Daniels’ “Major Moves” initiative, which financed 87 roadways, constructed or renovated 60 interchanges and fixed or replaced a quarter of Indiana’s bridges, “with no new state debt and no increase to taxpayers,” according to the Indiana Department of Transportation.

The deal did not benefit only Indiana’s infrastructure budget — it also proved to benefit a web of politically connected companies that had delivered big money to Daniels.

The Northwest Times reported that legal and consulting firms paid by the Daniels administration to work on parts of the deal made more than $90,000 worth of contributions to Daniels’ election campaigns. An IBT review of state documents found a similar trend with the lobbying and public affairs firm, Bose, that represented the private toll road consortium. As Macquarie and Cintra faced the prospect of oversight from the Daniels administration, Bose delivered more than $114,000 to Daniels’ reelection campaign once it was hired to lobby for the private consortium overseeing the road.

The companies’ management of the toll road drew controversy over everything from emergency management to toll increases and wages.

In September 2008, for example, Indiana taxpayers were forced to cover the costs of suspended tolls during a flood, according to a report by the Pew Charitable Trusts. The nonprofit also noted that, on one occasion, “the operators did not allow state troopers to close the road during a snowstorm, claiming it was a private road.” Meanwhile, the consortium began raising the toll rate — a central reason for the road’s 21-percent decline in traffic between 2006 and 2010, according to a Congressional Budget Office report.

“People got excited, but essentially, the taxpayers are just going to have to pay higher tolls,” Indiana State Rep. Matt Pierce, a Democrat, told IBT. He added that constituents had often complained that maintenance of the road and its signs and facilities was lacking, but that residents didn’t know where to direct their complaints when faced with an opaque consortium of contractors and stakeholders. Either way, he said, “with the companies, they’re just concerned about their bottom line.”

Even as Indiana drivers paid those increasingly higher tolls, the CBO report noted that the road’s maintenance and operations costs fell from $66,300 to an average of $59,200 per lane mile between 2007 and 2010.

“Much of the reduction in costs” of public private partnerships like the toll road, according to the federal agency, “appears to have come from lower labor costs: The private managers eliminated or reassigned many workers and replaced them with new employees who earned between 25 percent and 40 percent less.”

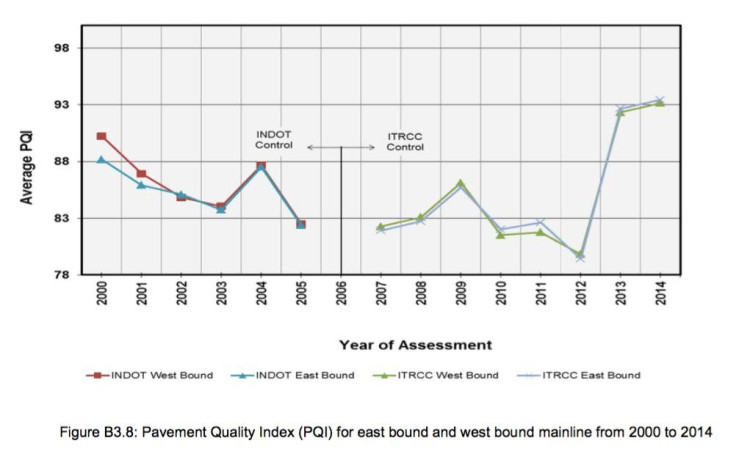

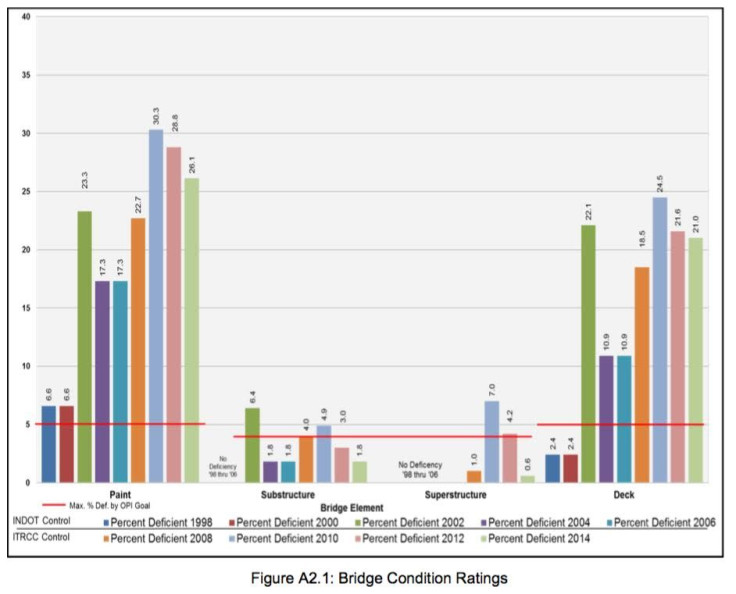

In annual audits obtained by IBT, the consortium also sounded alarms about the deteriorating conditions of bridges on the road after it was privatized. While its reports noted an improvement in the road’s pavement, a 2010 report obtained by IBT said that “statistically, all bridge element conditions have worsened in the aggregate since the previous assessment.” A 2014 audit showed that 21 percent of concrete bridges over the highway had become structurally deficient — a near doubling of the deficiency rate in the eight years since the road had been privatized, and well above the 5-percent deficiency rate that state officials set as a maximum limit.

The ITRCC did not respond to requests for comment from IBT. The Indiana Finance Authority deferred all questions on operation of the road to the ITRCC.

“Consider Reverting The Toll Road To State Control”

After Pence was elected to succeed Daniels in 2012, he quickly faced a crisis over the toll road — one that ended up illustrating his firm commitment to privatization.

In September 2014, citing weaker-than-projected revenues from tolls, the Cintra-Macquarie consortium filed for bankruptcy. At the same time, state documents revealed that the Indiana Finance Authority had become “very concerned about the deteriorating condition of the toll road’s travel plazas.”

Democratic Sen. Joe Donnelly urged Pence to consider following through on Daniels’ original promise to invoke the bankruptcy clause in the privatization contract, disband the private consortium and bring the road back under public management.

“Both the Indiana Department of Transportation and the ITR Concession Company have acknowledged that the current quality of road maintenance and service plazas has not lived up to the most basic standards of service and cleanliness expected by travelers and their families,” Donnelly wrote in a letter obtained by IBT. “As IFA evaluates options for the future of the toll road, I ask that you prioritize maintaining safe and appropriate road conditions, the adequate staffing and service of toll booths, and the good conditions and cleanliness of rest plazas and restrooms. If these conditions cannot be met, I ask that you consider reverting the toll road to state control so we can begin the task of restoring the toll road’s reputation and quality.”

Donnelly’s argument was buttressed by an analysis by College of William and Mary professor John Gilmour, which estimated that Daniels lost Indiana millions by leasing the road. His findings contrasted with a state-commissioned study’s projection that it would rake in close to $2 billion less in toll revenue if it held onto the road.

Pence rejected Donnelly’s request. Instead, the Pence-controlled Indiana Finance Authority opened up a new round of bidding to resell the lease. Among the bidders were two northwest Indiana counties who argued that they were better positioned than foreign firms to maintain the local road.

Friedman, the attorney who represented one of the counties, said he faced “outright hostility from the Indiana Finance Authority."

An IFA spokesperson disputed that claim, asserting that the counties' bid "was not inhibited from consideration.”

Pence’s administration commissioned accounting firm KPMG to evaluate the different scenarios for the road, but refused to release the firm’s findings. The company did not respond to multiple requests from IBT to review the report.

Pence’s administration ultimately rejected the counties’ proposal, and instead allowed another foreign investor to take over the management of the road. A year after Pence's decision, proponents of public ownership said Pence’s decision had harmed the state.

“It is clear to anyone who has driven on the toll road that conditions have worsened, and continued state or local ownership could have avoided this situation,” Donnelly said in 2016.

“This Project Will Continue Indiana's Strong Track Record”

The Indiana Toll Road wasn’t the only highway shaped by Pence’s privatization fervor. Before Pence had even taken over from Daniels in January 2013, he was already eyeing public-private partnerships as an option for the construction of a remaining segment of Interstate 69 that runs through the southern part of the state.

Just as the Indiana Toll Road was heading for bankruptcy in 2014, Pence and Indiana Republican lawmakers approved a consortium led by Spanish firms — predominantly subsidiaries of the infrastructure conglomerate Isolux Corsan — to oversee the construction and management of a 21-mile upgrade of I-69. In addition to over $100 million in funding from the state, with more to come on an annual basis, the public-private partnership received $243 million in tax-exempt private activity bonds (a federal funding mechanism that, within the Department of Transportation, has aided many similar infrastructure initiatives helmed by foreign firms). Trump’s fiscal year 2018 budget proposal suggests lifting the DOT’s $15 billion cap on those bonds.

“The private sector can harness a different character of innovation to find greater efficiencies, and this project will continue Indiana’s strong track record of partnering to deliver quality projects on budget and ahead of schedule,” Pence said of the I-69 privatization project.

Only two years after winning the contract, Isolux Corsan faced a notice of “failure to cause prompt payment” from the Indiana Department of Transportation; the Spanish conglomerate was nine months behind on its payment to subcontractors, the Indianapolis Star reported in April 2016.

Although the subcontractors eventually received their payments, the project itself began to stall at the start of the following year, with an 18-month delay pushing expected completion back to May 2018, according to the Star.

Two months after taking office, Pence’s successor, Gov. Eric Holocomb, told a local radio station that the I-69 project was “on track." But only weeks later, Holcomb’s administration announced that the state was taking back control of the project, terminating the contract with the private operators.

In a June report , the Indianapolis Star found that the project’s construction period correlated with a nearly 48-percent spike in car accidents on the roadway, and a 59 percent rise compared to four years earlier — likely costing hundreds of thousands of dollars in insurance claims.

“Taxpayers Won’t Let You Raise Taxes”

As Pence now helps lead Trump’s federal infrastructure initiative, Indiana remains a flashpoint for debate over the benefits and pitfalls of public-private partnerships.

Former Indiana Gov. Daniels, for instance, says that as lawmakers review the Trump administration’s Indiana-inflected privatization initiative, they should not view the toll road’s bankruptcy as a reason to avoid public-private partnerships.

“The investors took a haircut, but you need to separate the loss that the investors had from the benefit to the taxpayers,” Daniels told IBT. “The least efficient way to do anything is for the government to do it itself. If there’s someone out there who knows how to do it, better to have them do it.”

State Rep. David Niezgodski, one of the Democratic state representatives who voted against the toll road deal, said Indiana’s experience under Pence should raise concerns about Trump’s plans. Those concerns are particularly acute, he said, because compared to government-run projects, public-private partnership deals tend to be shrouded in secrecy.

“To the extent that the description comes out on a piece of paper that says everything is good and everything is fine… you should at least have awareness of who you’re dealing with,” he said. “You can’t use smoke and mirrors.”

David Wolkins, the sole Republican state representative who voted against the toll road deal back in 2006, suggested that the deals are the only logical way to fund major infrastructure projects in a political culture that is so hostile to taxes.

“There’s a general anti-tax sentiment out there,” he said. “Anything new is either going to have to be a toll road or a public-private partnership, because taxpayers won’t let you raise taxes.”

Donald Cohen, the executive director of the government contract policy think tank In the Public Interest, said the deals mislead taxpayers into thinking there are no real costs associated with improving infrastructure.

“They say, ‘If we sell it to the private sector, we don’t have to pay for it,’ and that’s outright b-------,” he said. As for Daniels’ argument that the state won out by receiving the money upfront, Cohen said, “They’re doing the math — the investors. You know: ‘We put in this much and we get this much back over time.’ They’re not stupid.”

Correction: This story originally included a typo, reporting that the I-69 project received $243,845 in private activity bonds. In fact, it was $243,845,000. The story has been updated.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.